Understanding Muṣaṣir’s character relies on the full corpus of archaeological and textual information presented in the preceding chapters. Combining the complete database of information concerning Muṣaṣir reveals aspects of its character under-discussed regarding its growth and religious cult. Much of Urartu’s history and the near totality of Muṣaṣir’s history remains unknown or understudied, relying on new archaeological or textual information. Interpretations of the historical geography or political organization of Urartu and Muṣaṣir depend on the extrapolating details in cuneiform records in the context of known locations. As such, the following discussion of Muṣaṣir’s religious architecture, relationship to Urartu, and reconstruction of Sargon II’s route rely on supposition. However, presenting possible interpretations based on new information enables discussion of larger issues in the study of Urartu and imperial expansion more broadly.

Despite the focus on the kingdom because of Sargon II’s eighth campaign, described in detail in his Letter to Aššur, the king's entry into the city deserves additional focus. Muṣaṣir’s mountainous character is evident from the totality of texts and archaeological material, but the interaction between its intermontane location and the Assyrian route reveals an alternative interpretation of the related relief on Sargon II’s palace at Khorsabad. The relief depicting the sack of Muṣaṣir provides insights into the domestic architecture of Muṣaṣir, paralleling the results of the archaeological analysis, as well as the possible existence of a local Ḫaldi cult alongside the imperial Urartian temple. Ḫaldi’s relationship to Urartu exposed the unreliable foundation of Muṣaṣir’s growth and how the Urartian royalty used a deliberate system of religious ideology as a tool in their imperial expansion.

Sargon II’s Route into Muṣaṣir

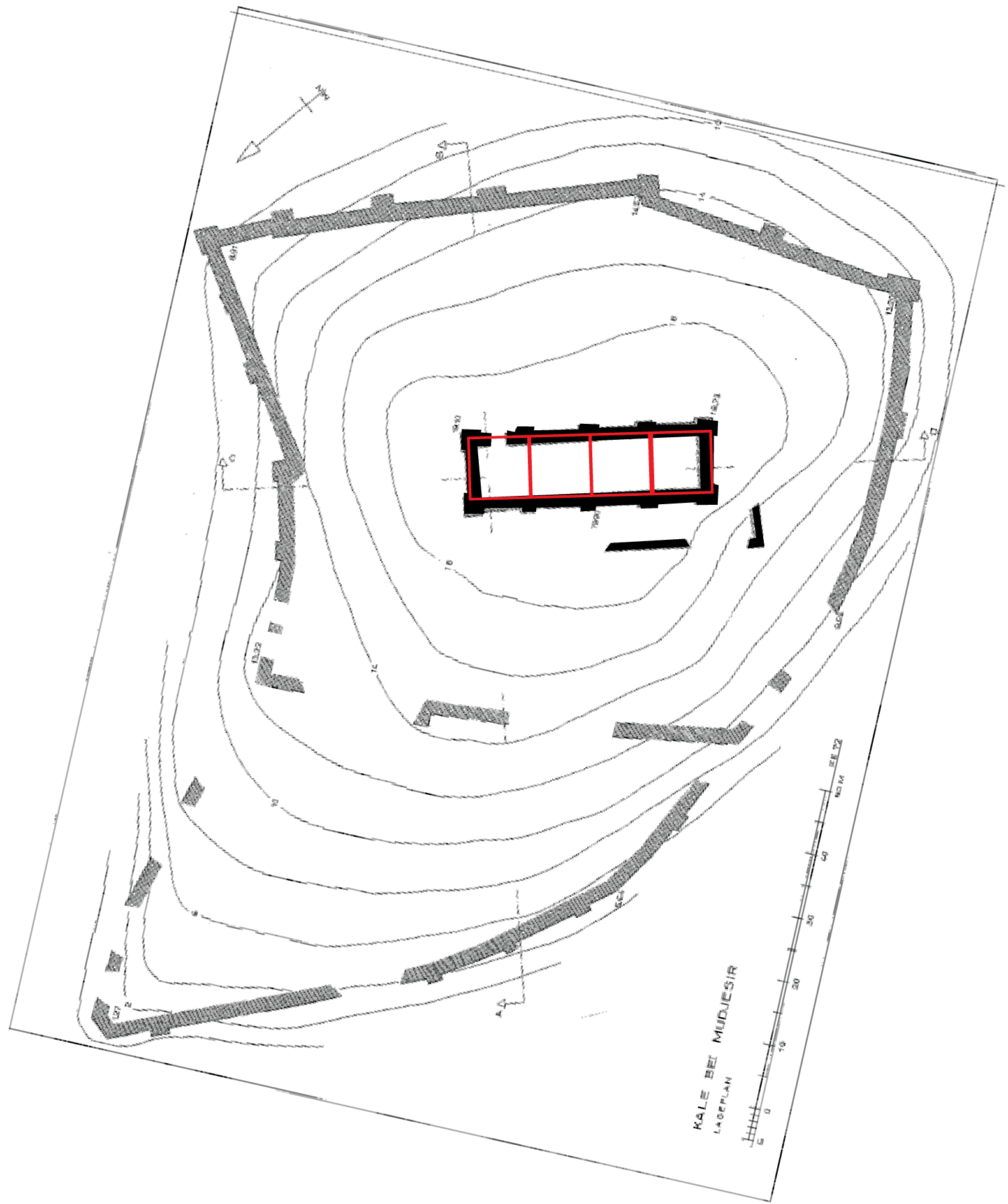

Many scholars have dedicated significant time and energy to reconstructing the route and toponyms of Sargon II’s eighth campaign. The fundamental impediment to this task is the lack of Assyrian toponyms with direct linkages to known sites in Iran. However, the relevant issue of Sargon II’s route for the research on Muṣaṣir is strictly concerned about the last leg of his journey, the sack of Muṣaṣir. Using Mudjesir’s location as a confirmed link to Muṣaṣir in the campaign text leaves one pertinent question: did Sargon II come to Muṣaṣir from the Kelishin Pass, burning villages along the Topzawa Çay valley on his destructive campaign to teach Urzana a lesson in disobedience to the Assyrian Empire, or did his armies sneak in a different route, coming from the west? The answer affects the interpretation of the destruction at Gund-i Topzawa – whether the Assyrian king caused the conflagration of Building 1-W Phase B – and the identity of the buildings depicted on the Khorsabad relief that provide contextual information about Muṣaṣir’s characteristics.

Most recent scholars’ reconstructions agree that Sargon II attacked Muṣaṣir going over the Kelishin Pass (Lehmann-Haupt 1931, 310, 325; Zimansky 1990, 4; Muscarella 2006; Fuchs 2018, 43–44), influenced by the existence of Išpuini’s stele and the road that follows that route. While Assyriologists began mapping the journey a century ago, more recent archaeological data invalidated many of the earliest publications’ foundational arguments and conclusions. Reconstructing Sargon II’s route, working backward from Muṣaṣir’s location at Mudjesir, reveals significant problems matching the area's geographic features. Sargon’s last location in Urartu proper is Uiše, a large fortress controlling an Urartian district. He then left Urartu and went to the “district of Ianzu, king of the land Na’iri” the king of Hubuškia. Sargon passes through Na’iri district, at a distance of four beru from Hubuškia. In this section of the text, he declares his reasoning for attacking Urzana and Muṣaṣir then initiates his attack. He takes the “road to the city Muṣaṣir, a rugged path,” forces the army to “climb up Mount Arisu, go up the mountain, Arisu, a mighty mountain that did not have any ascent, (not even one) like that of a ladder.” He then crosses “the Upper Zab River, which the people of lands Na’iri and Ḫabḫu called Elamunia River, in between Mounts Šeyak, Ardiskši, Ulayu, and Alluriu.” The text describes the mountains as “lofty mountain ranges, and narrow mountain ledges,” forming “no pathway for the passage of (even) foot soldiers,” and are “thickly covered with all kinds of useful trees, fruit trees, and vines as thick as a reed thicket.”

Among these mountains are “gullies made by torrential water – the noise of which resounds for the distance of one league, just like the thunder of Adad.” At that point, he goes along a route “no king had ever crossed and whose remote region no prince” had seen. During the passage, he boasts that he felled “large tree trunks” and hacked through “narrow places along their (mountain) ledges” that were “(so) narrow that foot soldiers could only pass through sideways.” Then Sargon II and his armies entered Muṣaṣir, sacking the city and capturing the royal family while Urzana escaped. Where then are the locations described by Sargon II after he departs Uiše? Uiše/Waisi was the Urartian stronghold for the southwestern part of Lake Urmia. Determining the route between Uiše and Muṣaṣir first requires determining the location of the Urartian fortress. Its exact location is debated, notably between Muscarella and Zimansky, who connected textual portrayals to archaeological evidence.

Zimansky proposed Uiše was the fortress site of Qalatgah, relying partly on the text’s classification of Uiše as the largest of Rusa’s fortresses, its position on the “lower border” of Urartu, and linguistic connections between Uiše and Ushnu (Zimansky 1990, 17–18). However, Muscarella (1971; 1986, 465–75) assigned the different toponym of Ulhu to Qalatgah, using the eighth campaign’s description of a rushing water source as a connection to the modern site’s adjacent spring. For the location of Uiše, Muscarella (1986, 474–76) and Salvini (1984, 46–51; 1995, 87) assigned the fortress of Qaleh Ismael Aga, further north along the western coast of Lake Urmia, given a partial reading of an in situ inscription at the site, its large size, and the cliffside castle’s proverbial “back” described in the Neo-Assyrian chronicle. Deviating further, Levine (1977, 147) locates Uiše significantly further to the north and west, “between the Zab headwaters and Lake Urmia,” not far from Hakkari in Turkey. Levine’s placement of Uiše, unlike those of Zimansky, Muscarella, and Salvini, did not rely on archaeological evidence or in situ inscriptions. As Uiše was one of the largest fortresses in Urartu, the continued absence of a substantial fortress archaeological site in that area makes Levine’s interpretation unlikely.

Figure 7.1 not yet available

Figure 7.1 not yet available

Regardless of the exact location, most recent scholars placed Uiše in somewhat similar regions southwest or central west of Lake Urmia. Hubuškia’s position, the following listed toponym in Sargon II’s trek to Muṣaṣir, is also ardently debated, split between northern locations, deep in the Taurus Mountains of Anatolia, or southern, in the valleys of the Zagros Mountains nearby Gawra Shinke Pass or Rowanduz. Following their more northern placements of Uiše, Muscarella, Salvini, and Levine locate Hubuškia to the north. Salvini (1967, 72) proposed the Bohtan Su plain, south of Lake Van in the Taurus Mountains, as the most likely location of Hubuškia, a spot in which Levine (1977, 143–44) explicitly agreed. Muscarella’s assignment of Uiše at Qaleh Ismael Aga forced him to locate Hubuškia nearby, near the modern Turkish-Iranian border (1986, 473–75).

The northern interpretations of Hubuškia rely either on each scholar’s chosen reconstruction of Sargon II’s eighth campaign or a view that equates Na’iri with Anatolia. Reade (1994) dismisses the northern location of Hubuškia as unlikely, using other Neo-Assyrian references to the polity as well as an alternative reconstruction of Sargon II’s route to locate Hubuškia to the south or southeast of Muṣaṣir, in the general area between Ushnu, Rowanduz, Pizhder, and Mahabad. Adding more specificity, Russell (1984, 195–98) locates Hubuškia near modern Rowanduz or the valley systems surrounding the town, using other Neo-Assyrian kings’ more southerly reference to the polity as supporting evidence. However, excavations and surveys by RAP in Rowanduz and the Diana Plain have not, at present, recovered any archaeological evidence that would confirm or deny that interpretation. Fuchs (2018, 43) placed Hubuškia south of Muṣaṣir, between Zamua to the south and Mannea to the east, in the general area of the valleys east of Rowanduz. In Fuchs's reconstruction of Sargon’s route, the king leaves Uiše, heads south to Hubuškia, and then loops back north, crossing over the Kelishin Pass. Sargon II’s journey over the pass remains the most common interpretation of recent route reconstructions (Lehmann-Haupt 1931, 310; Zimansky 1990, 4; Kroll 2012c, 11–12). However, do the geographic features depicted between Hubuškia and Muṣaṣir align with the known topographical attributes?

Two geographic landforms missing in the proposed route over the Kelishin Pass are the “Upper Zab,” known as Elamunia to the locals, and the gullies or waterfall that “resounds for the distance of one league.” The first, the Upper Zab, has no clear parallel in the area’s geography. While contemporary names of rivers and their tributaries do not align precisely to the Assyrian perception of those watercourses, one can assume two details: that whatever body of water termed the Upper Zab was at least a somewhat significant water feature and that it was a tributary of the Upper Zab River, in some perceived way. No such river exists when crossing over the Kelishin Pass from anywhere on the western side of Lake Urmia. The most significant water feature is the Godar River, which flows eastwards from the Zagros Mountains towards Lake Urmia, in the opposite direction of the Upper Zab. Even if one assumes that the scribes of Sargon II’s texts took creative liberty with the river’s size, the only river in this route is the Topzawa Çay. While this stream eventually combines to form the Upper Zab, it occurs after merging with dozens of other small tributaries. While Lehmann-Haupt (1931, 140) suggested the Topzawa Çay as Elamunia, the stream is the least likely interpretation. The Barasgird River is the most likely of the major rivers near the Kelishin Pass to qualify as a major tributary of the Upper Zab, with its gorge and surrounding mountains fitting Sargon II’s tales of treacherous passage. However, no route crossing the Kelishin Pass would intersect that river. Only a northern positioning of Hubuškia and a southward trek, as Levine reconstructs (1977), would pass that river, a fact established as unlikely and practically impassable.

Assuming Sargon II’s route crossed the Kelishin Pass and moved directly to Muṣaṣir, the Topzawa Çay is the only likely candidate as Elamunia, but the area is also absent the mighty gullies or waterfalls of the text. Personal travel on the road leading to the Kelishin Pass did not reveal a thundering waterfall. Searching satellite imagery and historical accounts concerning the rivers east of Sidekan did not show any features that could conceivably be called a waterfall. Although the absence of a waterfall and the diminutive Topzawa Çay are not enough to refute that Sargon II’s route passed over the Kelishin Pass, the primary reason for reconstructing the Neo-Assyrian’s path over the pass relies on one central argument, the Urartian royal road. Along with the Kelishin Stele, the Topzawa and Movana stelae locations established the Urartian “royal road” from Lake Van to Muṣaṣir ran by Lake Urmia, passing each of the Urartian inscriptions on the route over the Kelishin Pass towards the cult center at Mudjesir (André-Salvini and Salvini 2002, 29–30). Even assuming Sargon II’s boast of no king or prince traversing this road denigrated the status of Urartian kings and princes, it ignores the multitude of Middle and Neo-Assyrian kings who seemingly passed through this area on their way eastwards. Further, the vivid portrayal of the treacherous path would ignore that this route was the primary conduit for Urartu-Muṣaṣir interactions, not a rugged backcountry track. With the lack of corroborating geographic evidence, what is an alternative route of Sargon II’s travel from Hubuškia to Muṣaṣir?

Following the proposed location of Hubuškia in the southern valleys, including the area around Piranshahr in Iran, Sargon II’s journey to Assyria may have begun by following the course of the primary modern road, crossing into Iraq at the Gawra Shinke Pass. The route between this path and Rowanduz was one of the principal pathways from Iraq to Iran in antiquity and modern times. Hamilton’s account of road building in this area supports its common usage. His path from Rowanduz eastwards to the Iranian border first left that city and followed the pre-existing caravan path (Hamilton 1937, 110–11). The Berserini Gorge forms a treacherous barrier, forcing the path to ascend 600 m to the town of Dergala before descending alongside the Choman River for the remainder of the route east (Levine 1973, 8). Although forming the most direct journey to Iran and Urmia plains, even in the 19th century, the quality of the road was poor and surrounded by “sharp ridges of rocks” and a series of smaller gorges between the Berserini Gorge and the border crossing (Pfeiffer 1854, 274; Hamilton 1937, 164). However, compared to the long and dangerous hike across the Kelishin Pass, crossing the Gawra Shinke Pass was fairly easy (Levine 1973, 8).

Unlike the route over the Kelishin Pass, this itinerary crosses a significant water feature, the Choman River. Further, the Choman River is a direct tributary of the Upper Zab River, merging with the Barusk River at Rowanduz then joining the Upper Zab River after flowing through the Rowanduz Gorge (Figure 7.2). Along with the reference to the river, the mountains surrounding this route may parallel those in the eighth campaign text. Although details about the Šeyak, Ardiskši, Ulayu, and Alluriu mountains in Sargon II’s eighth campaign do not provide enough detail to definitively align them with any geographic features, the hyperbolic description of Arisu, “that did not have any ascent, like that of a ladder” is intriguing. The route from Gawra Shinke passes at the base of the Halgurd and Cheeka Dar Mountains, the two highest mountains in Iraq, which could easily be mistaken for one mountain with two peaks. One would expect Sargon II and his scribes to take note of such an imposing feature. Also visible to the south of this route is the Qandil Mountain, another of the country’s tallest peaks, another prominent feature to record. Reade’s (1994) reconstruction of Sargon II’s path, with Hubuškia around Piranshahr or Rowanduz, also interprets this watercourse as Elamunia.

The other feature of the Assyrian text absent along the reconstructed route over the Kelishin Pass is an associated waterfall or torrential gully. Another convincing argument for Sargon II’s route crossing Gawra Shinke on the way to Muṣaṣir is the Kani Bast waterfall. Located approximately 4 km south of the Choman River and modern Road, Kani Bast is the tallest waterfall in Iraqi Kurdistan (Rudaw 2019). The Assyrian text notes that the waterfall was heard at a distance of “one league [beru]” provides another supporting connection, emphasizing the water’s acoustics rather than its visuals. An Assyriologist from this region of Iraq, Dlshad Zamua (2017, 3), previously connected this waterfall to that in Sargon II’s account. Although he did not present the evidence behind this link, the magnitude of this water feature and the Choman River’s possible identity as Elamunia substantiate this.

An remaining question is how did Sargon II and his expeditionary force reach Muṣaṣir from the Choman River? The two previously discussed routes into Sidekan are the new road – beginning in Shaikhan, ascending the mountainside, descending into the Hawilan Basin – and the old road – starting from the western banks of the Barusuk River, tracing the hillside of the Sidekan River heading to Mudjesir. Either route, from Choman, would involve passing by the precarious Berserini Gorge, crossing the Diana Plain, and scaling another substantial mountain. While not an impossible journey, the text’s following four lines do not match the length and rigor of that trek. However, an analysis of the terrain using GIS tools reveals an alternative route that fully parallels Sargon II’s narration of his entry into Muṣaṣir.

With one known point at Mudjesir and one proposed location along Sargon II’s route at Choman, running a least cost path (LCP) analysis between the two locales generated a route the algorithmic calculated as most expedient. When using tools like LCP, the scholar’s role is to combine human intuition and contextual knowledge to determine if the given path is a suitable facsimile of reality. The LCP process for Sargon II’s route used ASTER as the DEM and Tobler’s Hiking function, as described in Chapter 6. The LCP exposed a previously undiscussed route into Sidekan that aligns with the description in the eighth campaign (Figure 7.2). Beginning from Choman, the resulting path follows the course of the Choman River, reaching one of the small tributaries near the village of Qasre, downstream of the Kani Bast waterfall. At that point, it heads northwest along a long valley, avoiding the treacherous Berserini Gorge while running parallel to the waterway, barely rising in elevation. After passing the Rust River, the route ascends, first up 400 m along a narrow valley, then another 500 m near the peak of Hasan Beg Mountain, encircling its western slopes. The route reaches a peak then descends into the Hawilan Basin, parallel to the new Sidekan road, joining the modern route not far from Mudjesir.

Although entirely computer generated, large portions of the LCP closely follow modern roads, confirming the feasibility of a path in antiquity. While none of the available travel accounts directly describe this path, a publication during the British Mandate describes a small but thriving village, Rust, along this route (Galloway 1958). Galloway and his companions traveled from Rowanduz to Galala, near the point the LCP departs from the Choman River and took a two-hour climb to the top of a “7000 foot ridge” near Rust (Galloway 1958, 361). Further evidence supporting this route’s use during Iron Age are caves along these ravines with Iron III ceramics, including the site of Bokadera (Kaercher 2014, 77–78). Other caves with similar material, located by the Soran Directorate of Antiquities but unpublished, exhibit characteristics typical of storage for transient populations.

Among the most compelling arguments that Sargon II traveled this path is the passage “whose area no king had ever crossed and whose remote region no prince who preceded me had ever seen.” While often disregarded in historical geography reconstructions, the proposed route fits that unique specification. Coming from Assyria, this route would be illogical and counterintuitive, requiring passing the Rowanduz and Berserini Gorges on the eastward trek, only to immediately backtrack to the northwest and take a considerable mountainous ascent. For the Urartian kings, their royal road over the Kelishin Pass served as a far more direct and secure route, passing through areas conquered early in the formation of the dynasty by Išpuini and Minua. With this underutilized route, Sargon II could successfully use the element of surprise, entering the kingdom and reaching the Ḫaldi temple in mere hours.

The Structures of the Muṣaṣir Relief

Reconstructing Sargon II’s route into Muṣaṣir described in his Letter to Aššur adds a new interpretation to the robust literature retracing the historical geography and presents a new perspective on the analysis of the relief from his palace at Khorsabad. While scholars cannot take the depictions on the relief, or any Neo-Assyrian relief, as purely literal, one assumes the artist, or official relaying contextual information, attempted to portray the setting at least somewhat accurately (Fuchs 2011). However, with the proposed western entry of Sargon II and his army into Muṣaṣir, the perspective of the Assyrian artist would face eastwards towards the structures of Muṣaṣir. Thus, the relief’s organizational structure, likely mirroring the geographic arrangement of Muṣaṣir, is split into three parts, the left, center, and right. Notably, Boehmer and Fenner (Boehmer and Fenner 1973, 513) also believed Sargon II entered the city from the west, and the relief reflected that city’s westward orientation. The proposed connection of the archaeological material to the relief is that the leftmost buildings represent typical domestic architecture like the structures at Gund-i Topzawa, the central Ḫaldi temple from Sargon II’s eighth campaign text was located in the excavated fields of Mudjesir, and the right structure depicts a local variation of an Urartian susi style temple located at the modern site of Qalat Mudjesir.

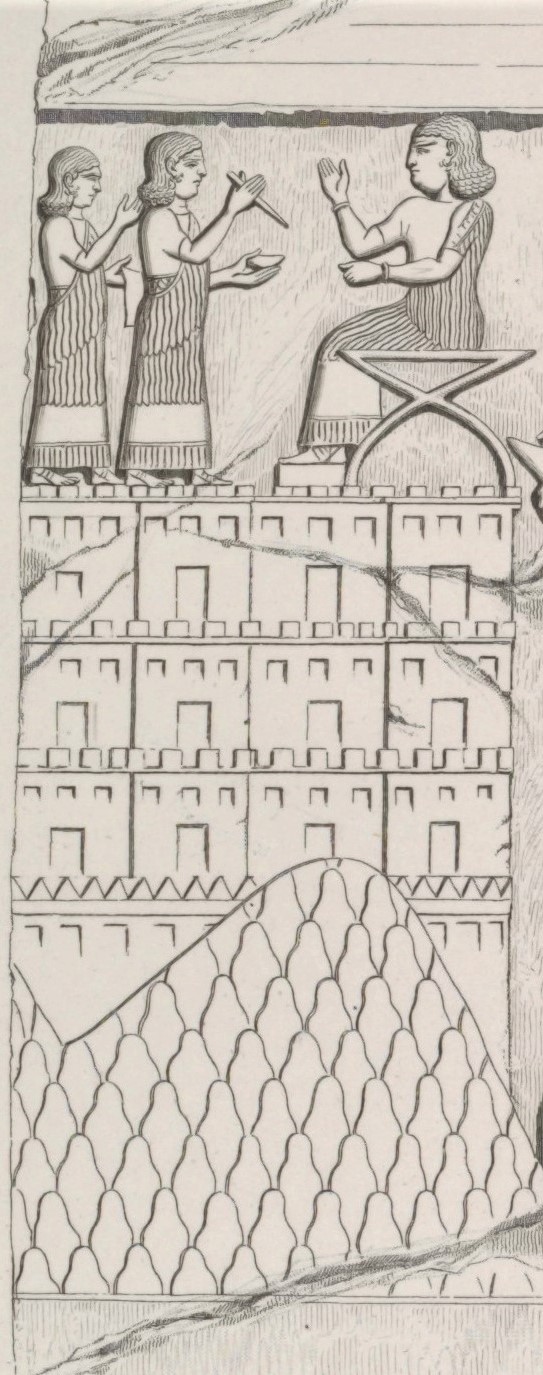

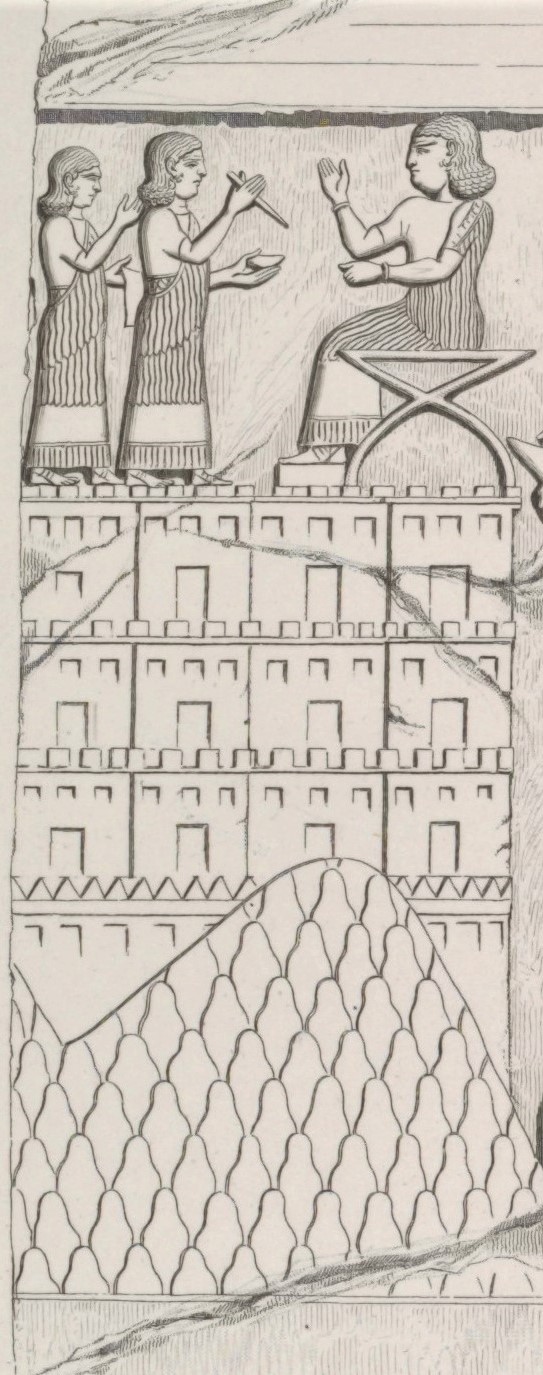

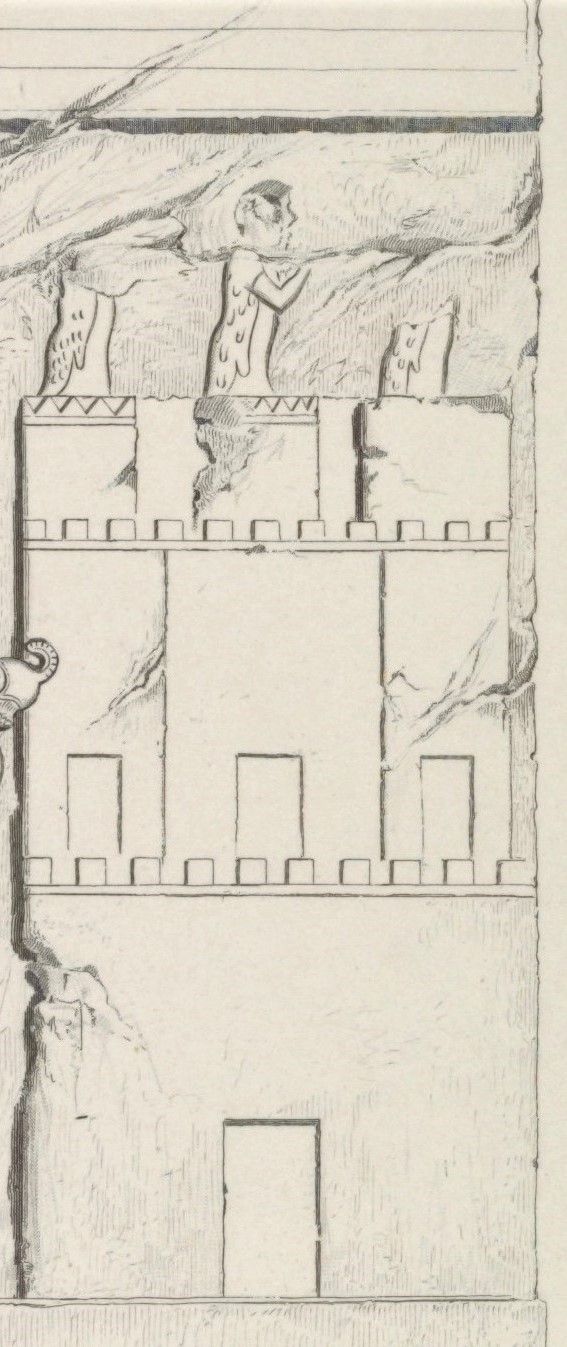

The left side of the relief depicts a scaled hill, with a multi-tiered cluster of structures on its top and sides and two left-facing figures standing in front of a person seated on a throne (Figure 7.1). The structures are divided into a grid three tall and four wide, with each square portraying a large door-like rectangle at its base, a row of three small squares above, and rows of apparent crenellation along the upper line. While many scholars in the century since Botta (1849) published a sketch of the relief have debated and proposed many interpretations about various aspects of the image, the consensus interprets the leftmost structures as residential buildings of some type. The only pertinent issue of disagreement is whether the three tiers represent terracing on the hillside, portrayed stylistically, or a single multi-storied structure. Forbes (1983, 46) believes the crenellation on top of each row of buildings represents the roofline of the structures, terraced three levels up the hillside. His argument relies, in part, on an apparent absence of typical domestic Urartian houses with significant second stories (Forbes 1983, 115). Excavations of Gund-i Topzawa Building 1-W Phase B indicate hillside houses in this area routinely had second stories, at least three meters tall in places, and support that the triple windows of the structures in the relief depicted a two-story building. Survey of the Mudjesir hillsides indicates, however, that the residential buildings were two-storied and terraced.

class="w-full max-w-3xl mx-auto border border-white/10 group-hover:border-[var(--color-brand-orange)] transition-all"

loading="lazy" />

Figure 7.3: Muṣaṣir Relief Detail. Left portion

(click to enlarge)

Agreeing with Forbes’ assessment of the crenelated terraced houses, Jeffers (2011) compares the structures to another Neo-Assyrian relief from the palace of Sargon II’s son Sennacherib at Kuyunjik. Multiple slabs illustrate the Neo-Assyrian king’s sacking of a mountainous kingdom, identified in the accompanying text as Ukku. Two slabs (Room I, Slabs 1-2; Room I, Slab 4a) contain depictions of structures comparable to those on the left of the Muṣaṣir relief (Figure 7.4). Each collection of structures has a large rectangular door and small square windows above. However, unlike the Khorsabad relief, the number of windows varies between one and two rows of three, and these buildings lack the crenellation of the Muṣaṣir houses (Jeffers 2011, 109–11). The structures to the right of Room I, Slab 1 reinforce the terracing theory of Muṣaṣir, as the irregular rooflines of the buildings would not correspond to stacked stories. Apart from the visual similarities of the houses in the two Neo-Assyrian kings’ reliefs, the geographic locations of Ukku and Muṣaṣir belie the characteristics of each settlement pattern.

Ukku was a small kingdom on the borderlands between Urartu and Assyria, with strong political connections to the kings of Lake Van. Radner’s (2012, 257–58) analysis of Sennacherib’s campaign path towards the kingdom, royal correspondence concerning Ukku’s king Maniye, and archaeological connection between Van and Hakkari led her to propose Ukku’s location in the modern Turkish province of Hakkari. Apart from the historical evidence, the linguistic connection between Ukku and Hakkari provides a convincing argument. The Hakkari province lies directly between the Turkish Van province, home of the Urartian kings, and the Iraqi Sidekan subdistrict. Like Sidekan, the province is exceptionally rocky and mountainous. Given the topography, the matching houses of Ukku and Muṣaṣir were structures adapted to the harsh environment. Although the imagery of other structures in Ukku, such as the multi-tiered fortress from Room SLVII, Slab 11-12, aligns with Assyrian depictions of Urartian architecture, the Muṣaṣirian structures do not share similar Urartian features (Gunter 1982; Earley-Spadoni 2015, 45). Despite the visual continuity suggesting a single variety of hillside houses in mountainous provincial Urartian areas, the multi-story hillside terraced domestic buildings are unrepresented in the standard imperial domestic typology (Forbes 1983, 115). As construction of the surveyed sites around Mudjesir paralleled the style of the excavated structures in Topzawa, one can assume the Ukku houses reflected a common architectural style of dispersed and unfortified domestic residences.

Figure 7.4 not yet available

Figure 7.4 not yet available

In addition, the locations and quantity of possible terraced buildings around Mudjesir match the houses on the left of the Muṣaṣir relief, providing further evidence of Mudjesir’s identity as Muṣaṣir and suggesting relatively commonplace domestic architecture surrounded the complex at the core of the kingdom. Sennacherib’s depiction of Ukku’s primary city parallels the apparent dispersed settlement around Muṣaṣir’s urban core. Ukku, on Room XLVIII, Slabs 11-12, had only a small Urartian-style fortress at its peak, with unwalled structures surrounding the citadel (Jeffers 2011, 108). Given that depiction and the completely absent illustration of a fortified structure from the Muṣaṣir relief, the unwalled domestic architecture surrounding Muṣaṣir’s temple is consistent with the archaeological attributes of Mudjesir.

Figure 7.5 not yet available

Figure 7.5 not yet available

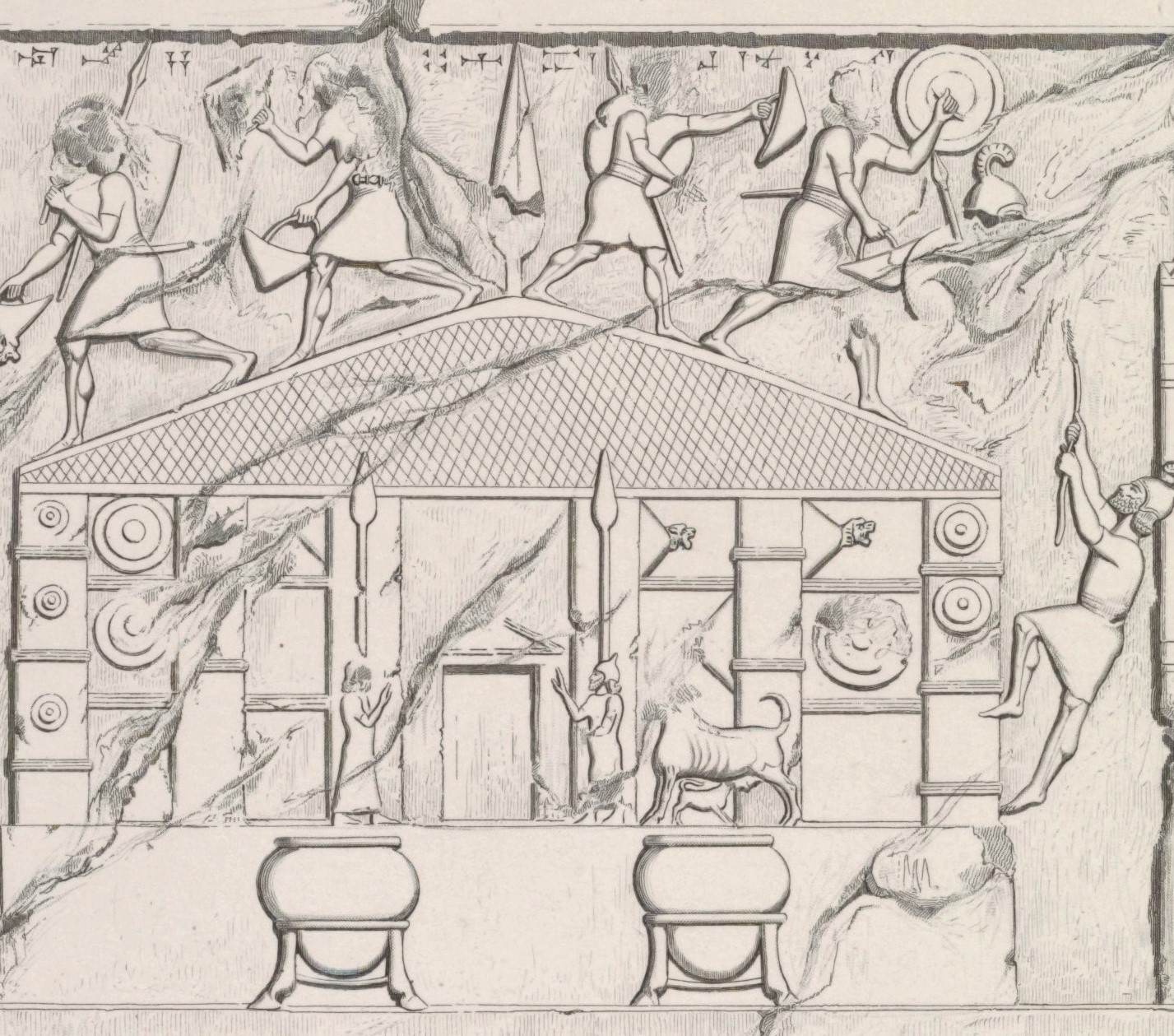

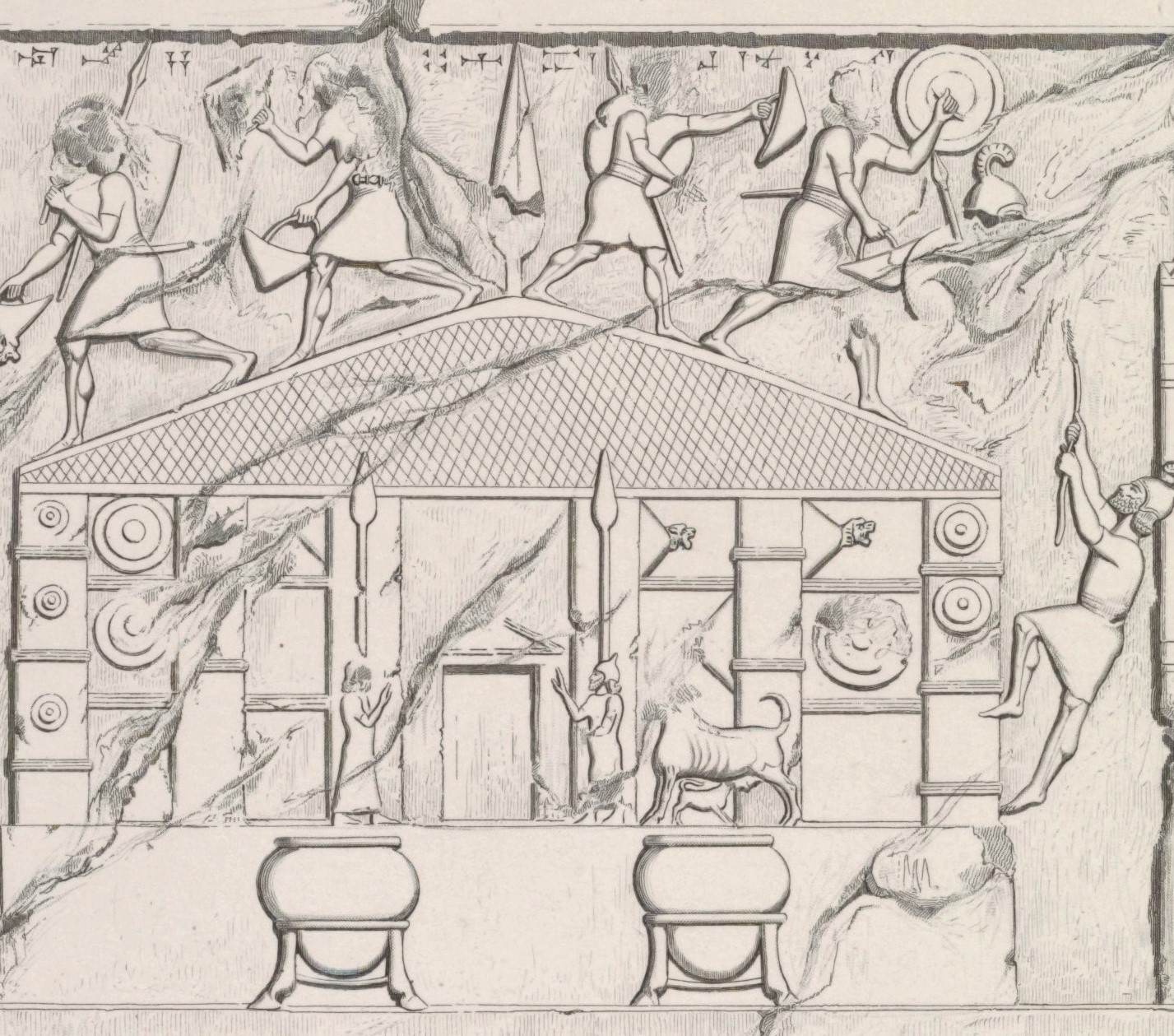

Determining the location and the remaining structures requires a close reading of the associated text and joining the archaeological material. The central (Figure 7.6) and right buildings (Figure 7.8) are often interpreted as the Ḫaldi temple and Urzana’s palace, respectively. The pitched roof and detailed iconography of the central building and residential appearance of the right building parallel the sack of the Ḫaldi temple and Urzana’s palace in Sargon II’s Letter to Aššur. The newly uncovered material from excavations at Mudjesir, Qalat Mudjesir, and survey of the surrounding area enables an alternative interpretation. Instead, the Khorsabad relief depicts two separate temples, the central one, described in the text as the Ḫaldi temple and associated with Urartian Ḫaldi iconography, and the right one, depicting a unique version of the archetypical susi tower temple. Sargon II’s scribes conflated Urzana’s palace complex with this temple structure, located at Qalat Mudjesir. The central temple’s large platform and spot in the relief’s middle indicate a likely position near Mudjesir’s excavated drain, a feature covered with a deep stone fill, believed to be a platform's base.

The Khorsabad relief’s detailed depiction of the central building alongside the lengthy narrative of Muṣaṣir in Sargon II’s eighth campaign text led scholars to focus on the building and its relationship to Urartu (Figure 7.4). The artistic details on the building’s face directly connect to probable Ḫaldi iconography, and the textual description of the Ḫaldi temple references features on the building. Among the notable decorative elements are spears, two flanking the main entrance and one at the roof’s peak, dual figures on either side of the doorway, and a cow with a suckling calf. While debated, Ḫaldi’s association with a spear appears as a frequent motif in artistic depictions of the god and at excavated temples (Zimansky 2012a). One of the few visual depictions of Ḫaldi on the Anzaf shield shows the god engulfed in flames holding a large spear (Belli 1999, fig. 17; Seidl 2004, 199). In addition, a seal from Ayanis seemingly depicts a figure worshiping an upright spear engulfed by flames (Zimansky 2012a, 718–19). The most explicit connection came from Ayanis, outside the Ḫaldi temple, where excavators uncovered a large spear that directly parallels the doorway spears in the relief. The inscribed object referenced Ḫaldi, and its scale and fragility indicated decorative use, like on the Muṣaṣir relief (Çilingiroǧlu and Salvini 1999, 56–58).

class="w-full max-w-3xl mx-auto border border-white/10 group-hover:border-[var(--color-brand-orange)] transition-all"

loading="lazy" />

Figure 7.6: Central Portion

(click to enlarge)

The eighth campaign's listing of booty taken from the Ḫaldi temple records goods connected to two features on the relief, the humans standing at the doorway and the cow with calf. The figures directly parallel the record of “4 divine statues of copper, chief doorkeepers, guardians of his (Ḫaldi’s) gates, (each of) whose height is 4 cubits, together with their bases, cast in copper,” with two of the statues in the artistic representation. At the height of four cubits, approximately 2.1 m, the main structure in the relief would measure around 6 m tall. In addition, Sargon II takes away “1 bull (and) 1 cow, together with her bull calf” made of copper, directly matching the cow and calf on the building’s right side. Given that both the text and relief are from the Assyrian perspective, there is no doubt of the building’s identity as the Ḫaldi temple. The archaeological linkage of the drain and stone platform connects the location to the text and artistic representation. As the primary temple at the god’s holiest city, many suggest the Urartian buildings dedicated to Ḫaldi across the empire replicate the form. However, the replicated Urartian Ḫaldi temple form observed at major sites seemingly does not resemble the Assyrian representation, raising the possibility of the relief’s rightmost building’s use as a temple.

As the chief deity of Urartu and royal protector, Urartian kings erected Ḫaldi temples at imperial outposts in a highly rigid and uniform style. Excavations of Urartian settlements uncovered at least ten foundations of these temples (Figure 7.7). Called susi temples, the closest translation of the Urartian term reads as “tower temple,” belying an aspect of their design (Salvini 1979, 581-82). The form of these temples followed a fixed layout with minimal variation. Each temple was square, with a small cella, a single door, and extremely thick walls (Forbes 1983:69). Large stone foundations up to 1.5 m thick, the only surviving floorplans of most temples, served as the structural base for mudbrick walls above. The Urartian builders placed the foundations, often made of limestone or andesite stones, directly on or sunk into the bedrock (Çilingiroğlu 2012, 297, 300). As a square, each wall was of equal length, ranging from 10-14 m long (Franke 2018). The height of the mudbrick walls’ preservation among the excavated susi temples is typically no more than a meter or two, forcing archaeologists to estimate the original height of the structures (Kuşu and Köroglu 2018, 114).

Figure 7.7 not yet available

Figure 7.8: (Image from Albenda 1986, pl. 133)

Each corner of the square building was buttressed, and the doorways were rabbeted, often with exterior steps leading to the long passageway through the broad walls into the cella. Cellas were also square, with dimensions of the walls varying between 4.5 and 5.5 m (Franke 2018). While not preserved in all susi temple examples, some, like Ayanis, had altars directly opposite the door, believed to be a pediment for a statue of the deity (Forbes 1983, 69; Çilingiroğlu 2001, 42). The cella floor was simple and smoothed, sometimes with minimal decorations like small stones or alabaster blocks (Çilingiroğlu 2012, 300). The square susi temple was in a complex surrounded by a courtyard and a parallel outer wall with dimensions of those complexes’ outer walls 21-30 m (Çilingiroğlu 2012, 295). The associated buildings surrounding the susi temples, outside the courtyard, consisted of storerooms and monumental residential buildings for the priests (Çilingiroğlu 2012, 305). Thus far, the only examples of these complexes are in walled Urartian citadels adjacent to royal palaces (Forbes 1983, 43).

Without freestanding susi temples, archaeologists must reconstruct the buildings using artistic representations, often using Muṣaṣir relief’s temple as a guide. The other notable visual depictions of Urartian buildings or temples are on the Adilcevaz relief (Öǧün 1967) and bronze Toprakkale model city (Barnett 1950, Plate. 1). The difference between the Muṣaṣir temple’s pitched roof and the tall, crenelated towers on the Adilvecaz relief (Figure 7.9) and Toprakkale bronze (Figure 7.10) complicate reconstructions of Ḫaldi temples. Both roof styles cannot exist simultaneously. Reconstructions of the susi temple are categorized by attempting to merge the ground plan of the susi temples and the visual representation of the Muṣaṣir Ḫaldi temple versus using iconography from the crenelated Urartian art to illustrate tower temple buildings. Relatedly, some scholars of Urartu insist on two variations of Ḫaldi temples, the square susi type from excavated Urartian imperial citadels and a unique type shown on the Khorsabad relief (Herzfeld 1941; Kleiss 1963; 1989). Belief in one susi type, typified by Sargon II’s depiction of Muṣaṣir, or two separate versions influenced the reconstructions of the square susi temples’ upper levels. A second Urartian temple variation is consistent with an interpretation of the Khorsabad relief’s rightmost building as a susi temple.

Figure 7.9 not yet available

Figure 7.10 not yet available

class="w-full max-w-3xl mx-auto border border-white/10 group-hover:border-[var(--color-brand-orange)] transition-all"

loading="lazy" />

Figure 7.10: Bronze Model City from Toprakkale

(click to enlarge)

One category of susi temple reconstructions that does not explicitly match the Muṣaṣir relief depicts the temple with tall towers and a flat roof. Tahsin Özgüç’s (1966, fig. 1) reconstruction of the susi temple at Altintepe was a square building with large flat towers on each corner, surrounded by columns and a flat-roofed portico (Figure 7.11). Another version, illustrating Toprakkale’s susi Ḫaldi temple, envisioned a tall structure with buttresses and extensive crenellation but did not believe the buttresses supported a tower higher than the main building, following the Toprakkale bronze model (Akurgal 1968, 15). Kleiss’s interpretation of the susi plan evolved over the decades, from 1968 to 1989. Kleiss’s later article (1989) argued Urartian susi buildings were distinct from the Muṣaṣir Ḫaldi temple’s design, with no pilaster structure or pillars at its front (Figure 7.12). The overall form of the temple mirrored Özgüç’s, a tall square building surrounded by a flat-roofed portico. He reconstructed four variations of the roofs, following the three representations on the Toprakkale bronze, Khorsabad, and Adilvecaz reliefs, plus one combination of a crenelation and a pitched roof (Kleiss 1989, 266). Sevin’s (2003, 216) version of the susi at Cavustepe had four towers projecting above the central building, like Özgüç’s, but with triangular dentils and crenelation like that of Akurgal. The most recent reconstruction, made with 3D visualization tools, modeled the whole of the Altintepe citadel, including the temple complex, adjacent mansion, and fortification walls (Kuşu and Köroglu 2018). The modeled susi building follows the design of the Adilcevaz relief and Toprakkale bronze, with four crenelated towers with dentils, 9 m tall, four small windows above a large arched doorway (Figure 7.13) (Kuşu and Köroglu 2018, 114-115).

Figure 7.11 not yet available

Figure 7.12 not yet available

Figure 7.13 not yet available

Figure 7.13 not yet available

The other category of susi temple alternative reconstructions proposes that the Ḫaldi temple of the Khorsabad relief followed the same architectural plan and style as the entirety of Urartian temples throughout the empire. Kleiss’s (1963, Figure 8) first attempt at a reconstruction precisely followed the Assyrian depiction of the temple, adding only an outer portico, front stairs, and perspective to the temple. While he later proposed an alternative view, the explicit translation of the relief into a three-dimensional perspective continues to be valuable in understanding a realistic depiction of the temple on the relief (Figure 7.14). Naumann (1968, 53) followed the Muṣaṣir illustration but added additional details like four windows on the front façade. In Forbes’s (1983, 95) comprehensive treatise on Urartian Architecture, he proposes the Muṣaṣir temple was a slight deviation from the typical susi tower-style temple, with characteristics seen in Kleiss’s 1963 reconstruction, but the plan generally followed the typical Urartian style. Çilingiroglu (2012, 525) rejected the division of Urartian temples into excavated susi temples and the Muṣaṣir Ḫaldi temple. His evidence included an inscribed bronze lion-head shield found near the Ḫaldi temple at Ayanis, with striking visual similarity to those on the Khorsabad relief and used as proof for a single temple style with pyramidal roofs. Franke (2018) did not offer a visual reconstruction but instead argued that Sargon II’s artists pulled forward perspective, taking liberties with the side walls to bring their view to the front. With the argument of altered perspective, the decorative features on the Ḫaldi temple at Muṣaṣir can be directly extrapolated to the susi temple, effectively following Kleiss’s 1963/1964 reconstruction.

Figure 7.14 not yet available

Figure 7.14 not yet available

The arguments for equating the central building on the Khorsabad relief with the Ḫaldi temple of the text and the archaeological excavations at Mudjesir seemingly confirm the placement of the building at that spot. However, the susi foundation form is unrepresented at that site, and the difficulties with equating tower temple layouts to the Ḫaldi temple are well documented. The recent excavation of Qalat Mudjesir provides evidence consistent with a temple structure resembling the Urartian susi style. While Michael Danti’s report is forthcoming, the building’s interior and architectural construction are completely incongruous with a fortress or palace. Instead, the general characteristics match the typical susi temple plan, with minor but noteworthy differences.

Like the excavated susi temples, the Central Building at Qalat Mudjesir consisted of large stone foundations with buttressing. The two longer sides, to the west and east, each had five buttresses. On the eastern wall, near the corner with the northern wall, was an off-center doorway. The building’s interior was almost entirely empty, with evidence of a high-temperature burning event and contained burned debris. Clay from the destruction was impressed with reed and grass, likely from the structure’s roof. While not a square, the buttressing, stone foundations, position at the center of a hilltop complex, and parallel walls of the Outer Bailey match the characteristics of a susi temple. The excavations of the sites at Mudjesir raise two questions relevant to Urartian religious architecture: Was Qalat Mudjesir a susi style temple for Ḫaldi? Could the central building on the Khorsabad relief depict Qalat Mudjesir rather than a structure in the Mudjesir lowlands?

The first question of Qalat Mudjesir’s possible identity as a susi temple runs against the conspicuous difference between its rectangular plan and the square plans of susi temples. The temple's measurements and positioning of its buttressing are consistent with a unique “quad-style susi” temple, a hence undocumented style of Urartian architecture. Qalat Mudjesir’s Central Building measures approximately 40 m x 13 m, with walls approaching 2 m in thickness. Overlaying a hypothetical square susi temple with 10 m long sides over each quartet of buttresses nearly perfectly aligns with the Central Building of Qalat Mudjesir (Figure 7.15). Effectively, this arrangement of buttresses is four susi temples connected, with the adjacent walls removed. Intriguingly, this suggests the single off-center door continued the traditional susi layout, but the northern square served as the entrance for the remaining three susi layouts. Thus, rather than one susi temple, the structure was four times the size but followed the architectural design of the archetypical structures across Urartu. Reasonings for the four-part temple structure or possible uses are completely speculative and will require further research. Apart from the unique quad-style susi layout, the building exhibits the typical features of a large stone foundation supporting mudbrick walls, buttressing, and an outer wall delimiting the temple complex. In addition, all of the known susi temples were on hills or mountains, visible from some distance away (Çilingiroglu 2012, 295). While the rest of the site remains unexcavated, the scale of the outer fortification wall and the Central Building’s relative placement are similar to the susi temple at Altintepe.

Once established that Qalat Mudjesir’s Central Building was a susi style temple, the pertinent question is whether that structure is the same Ḫaldi temple depicted on the center of the Khorsabad relief. One issue is this equating is the symmetrical facade depicted by Sargon II’s artists, compared to the quite offset door of Qalat Mudjesir. While Qalat Mudjesir’s building could, in theory, have a pitched roof like the building from the eighth campaign, an angled roof of 20° (as on the relief), 40 m in length would be an impressive engineering feat, with the roof ridge 6 m above the walls. Using the four cubit height of the statues as a scale, the entire height of the structure would reach 18 m. Such a towering structure would undoubtedly be depicted, highlighting its vertically instead of the somewhat squat temple on the relief. Further, while the Assyrian artists took creative liberties with perspective, their depiction of the Ḫaldi temple leaves out the multi-tiered hill and walls surrounding Qalat Mudjesir’s central building. Sennacherib's depiction of Ukku’s sack, a similar mountainous kingdom to Muṣaṣir, portrayed that urban center as unwalled except for the uppermost citadel (Jeffers 2011:90-94). Even with the style of Sennacherib’s father, Sargon II, the representation of the central building on the Khorsabad relief is incongruous with the Qalat Mudjesir excavated remains.

Figure 7.15 not yet available

Figure 7.15 not yet available

The proposed alternative is that the right building on the Khorsabad relief represents Qalat Mudjesir. In the same slab from Sennacherib’s palace at Kuyunjik detailing the destruction of Ukku, Jeffers (2011, 106-7) proposes a structure in the upmost citadel was an Urartian susi tower temple (Figure 7.5). While barely visible, the building’s general shape aligns with the single building of Ukku. Despite the simple architectural visualization of Muṣaṣir’s right building, its top appears to have three towers with crenellation and dentils on their peak more similar to the Adilcevaz relief and Toprakkale bronze than the residential buildings on the left.

The central building of the relief then represents another version of the Ḫaldi temple, the one described by Sargon II in the inventory of plunder but still undiscovered. Entering from the west, the topography of Mudjesir would dictate the central building, the Ḫaldi temple, which lie in the center of the small valley surrounded by the settlement of Muṣaṣir. Both the relief’s depiction and the text’s iconography align with the central building, but the question arises of why Sargon II’s eighth campaign text is absent references to a second temple of the susi type. One explanation for this omission is that the Assyrian invaders incorrectly identified the complex at Qalat Mudjesir as Urzana’s palace.

Among the possible justifications supporting Sargon II’s misidentification of Urzana’s palace is the vast quantity of loot taken away from the palace. Albeit far less than that in the Ḫaldi temple, the Assyrians took away 167 talents of silver, copper, and tin. While not an extraordinary quantity of fine goods, the natural resources and wealth around Sidekan likely did not allow the Muṣaṣirian king to amass such wealth without the sponsorship of the Urartian king or as tribute in pilgrimages to the Ḫaldi temple. Further, Urartian palaces were often near temples, terraced or on low hills, describing Qalat Mudjesir (Forbes 1983:42-46). Rather than a vast defensive citadel for defense and control of surrounding areas that Urartian kings built in their expansionary activities, Qalat Mudjesir is more comparable to Altintepe. That site was primarily religious, with a large temple complex covering most of the walled area, surrounded by smaller buildings believed to support the temple's activities (Karaosmanoğlu and Yılmaz 2014). Urzana’s role at Muṣaṣir, under the indirect control and influence of the Urartian kings, was as a custodian of Ḫaldi, and his kingship was undeniably predicated on that support. Thus the Muṣaṣirian royal complex supported the temple activities, not as an independent entity for the king’s enjoyment. The scant depiction of the palace-susi complex on the right of the Khorsabad relief may be explained by Sargon II’s intense focus on the Ḫaldi temple or an absent understanding of Urartian-style architecture. The relevant takeaway from the proposed susi temple with Urazana’s palace is the existence of two Ḫaldi temples at Muṣaṣir in different styles. The central Ḫaldi temple may reflect a preexisting Muṣaṣirian cult to Ḫaldi, while the right’s unique susi style would serve as the archetypal example of Urartian architecture. The possible reasons for the existence of a dual temple connect to the founding of the Urartian religious cult and the early history of Muṣaṣir.

Origins of Muṣaṣir, Ḫaldi, and Urartian Religion

One of the continually perplexing questions in Urartian scholarship is the origin of the ruling dynasty and, relatedly, their relationship to Ḫaldi (Kroll et al. 2012, 105). The dawn of the Ḫaldi cult in Muṣaṣir directly relates to the beginning of the Urartian dynasty, as the reasons for Ḫaldi’s position at the top of the Urartian pantheon directly follow from interpretations of the king’s ancestry. If the Urartian royalty originated from Muṣaṣir or nearby areas, migrating to Lake Van and founding their dynasty, the existence of Ḫaldi is explained easily by that hereditary veneration. However, if Lake Van and its surrounding environs began the dynastic tree, Ḫaldi’s position as the supreme god is more inexplicable, likely the result of a deliberate program of constructing a comprehensive imperial ideology.

Many of the arguments for an Urartian ancestral homeland nearby Muṣaṣir rely on the king’s reverence as Ḫaldi as evidence, but removing that connection reveals a relative paucity of data in support of that hypothesis. The Muṣaṣir ancestral relationship relies on a location for the early Urartian royal city of Arazškun south of Lake Urmia, references to an ancestral city in Sargon II’s Letter to Aššur, the coronation of the crown prince at Muṣaṣir, and possible connections to Bronze Age Turukku and Kakum, introduced for the first time in this dissertation (to my knowledge).

Shalmaneser III’s campaigns against Urartu signify the emergence of the empire on the world stage as a major threat to the Neo-Assyrians and provide multiple toponyms with contextual information regarding the earliest Urartian occupation. Specifically, Shalmaneser III’s 3rd year campaign in which he defeats the first recorded Urartian king, Arame, and destroys the “royal city” of Arzaškun, subsequently traveling to Gilzanu and Ḫubuškia. As the earliest reference to a royal city of the Urartians, Arzaškun’s location naturally provides insights into the homeland of the ruling elite. The path of Shalmaneser III’s earlier campaign, in his ascension year, overlaps with the toponyms of the 3rd campaign, triangulating Arzaškun’s position. That campaign moved from Ḫubuškia to a “fortified city of Aramu the Urartian” called Sugunia, down to the sea of Nairi (Lake Urmia), receiving tribute from Gilzanu on his return to Aššur. Ḫubuškia, as discussed in the section on Sargon II’s route, likely lay in the vicinity of the Gawra Shinke Pass and Piranshahr. Sugunia’s location is in the southern Lake Urmia region (Salvini 1995, 28; Schachner 2007; Fuchs 2012, 138). Gilzanu, likewise, was either based around the site of Hasanlu (Reade 1978) or further east towards Mahabad or Miandoab (Kroll 2012b, 166). Despite the parallel toponyms, Arzaškun’s location is under far more extensive debate.

Despite the accompanying toponyms from southern Lake Urmia suggesting Arzaškun was located nearby (Salvini 1995), the preceding locations of Shalmaneser III’s route indicate the journey began in the west before moving east and southwards to Lake Urmia. The start of the campaign passed cities like Mutkinu, on the bank of the Euphrates, and Bit-Zamani, located in the Euphrates headwaters of the Taurus Mountains (Kroll 2012b, 167). Traveling east to Lake Van and subsequently to the western coast of Lake Urmia is consistent with the known concentration of later Urartian fortresses and the well-trodden road from Van to polities in the south of Lake Urmia like Ḫubuškia. Despite Salvini’s (1982, 1995) and Haas’s (1986, 23, 26) suggestion of Arzaškun’s location in the proximity of southern Lake Urmia, recent publications by Urartian philologists and archaeologists advance that the royal city was in Van (Burney & Land 1971, 127-130; Russell 1984, 198; Zimansky 1985, 48-50; Burney 2002; Kroll 2012b). Further, excavations of Karagündüz by Sevin (2003, 1999) uncovered a material culture in the early Iron Age with direct connections to those that arose with imperial Urartu in the succeeding centuries. In contrast, the extensively studied early Iron Age material culture of southern Lake Urmia does not possess the same continuity to Urartu (Kroll 2012b, 167; Danti 2013).

An additional argument for a southern Urmia origin of Urartians comes from another Neo-Assyrian text, more than a century later. A passage in Sargon II’s eighth campaign describes the “ancestral city” of Rusa as Arbu, a city in Armarijali near Lake Urmia, resulting in the proposed location of Armarijali as the origin of the Urartian elites. However, if Sargon II’s adversary was Rusa Erimena, a usurper to the Urartian throne, Arbu may refer to that specific kings’ homeland rather than the whole of the Sarduri dynasty (Chapter 2). The same line in the text also describes a city, Riyar, “Ištar-duri’s [Sarduri’s] city” but does not use the same qualifier of the ancestral city. The following lines note his royal family resided in their environs, but the subject of the possessive is unclear in this context. Given the preponderance of Sarduri cities around Urartu founded during his expansionary process, the reference to a Sarduri city alone is insufficient evidence for the town’s location as the Urartian homeland.

Further proof of an ancestral connection is the belief in the process of selecting the next Urartian ruler at Muṣaṣir. This argument relies, in part, on the oft-cited belief that the Urartians crowned the crown prince at Muṣaṣir, a likely overinterpretation of a passage in the eighth campaign text (Kroll et al. 2012, 28). Sargon II’s text stated that “the prince, the shepherd of the people of the land Urartu they bring him and make the one among his sons who was to succeed to his throne enter into the city Muṣaṣir...” “In front of his god Ḫaldi, they place upon him the crown of lordship and have him take up the royal scepter of the land Urartu.” While the Assyrian text seemingly describes this ceremony, the Kelishin Stele does not parallel those activities, and evidence of an Urartian crown prince remains debated. Apart from the inscriptions of Išpuini and Minua that imply Minua’s deputized role comparable to a crown prince, only one other Urartian prince appears alongside his father in royal inscriptions. The name of Minua’s only son, Inušpua, occurs in some of the texts from the latter period of Minua’s reign, but that person never ascends to Urartian kingship. Instead, his assumed brother Argišti takes the throne (Fuchs 2012, 102-106). If the king brought a son to Muṣaṣir for coronation as crown prince, the practice was seemingly short-lived and undocumented in Urartian inscriptions. Even assuming the Urartians enthroned their royal line at Muṣaṣir, the proposed ancestral connection still relies on the city’s holiness, a circular argument in explaining Muṣaṣir’s importance.

A final datum of evidence supporting the Urartian king’s original genesis around Muṣaṣir and Lake Urmia comes from Chapter 2 of this dissertation’s study of the Turukku and Kakmum. As a brief synopsis of the presented evidence, the Turukku were an ethnically Hurrian confederation of minor kingdoms under the leadership of a single Turukku king, often ruling from the city of Itabalḫum. Reconstructions of the historical geography of the Early Bronze Age place the Turukku in the series of valleys south of Lake Urmia, although archaeological excavations in survey have yielded no corroborating evidence. The possible connections of the Turukku to Urartu and its founders are both ruling classes’ Hurrian linguistic identity and the confederated nature of the kingdom. However, while Zimansky (1985, 48-9) postulates the Assyrian pressure of raids forced the consolidation of independent kingdoms into a single Urartian state, that dynamic parallels merely parallel the Turukku. Occurring centuries later, there is no reason to believe a repeat of the political fabrication requires an ancestral connection.

An enemy of the Turukku, the nearby polity of Kakmum disappeared in the Bronze Age, but a derivation of its name reappeared centuries later during Sargon II’s campaign against Urartu. While Kakmum’s location is more debated, possible locales are the Pishder Plain, somewhere south of Rania, or the area around Rowanduz and Soran. Compared to the Turukku, however, the Kakmum people appear more often in the texts and politics of Mesopotamia, implying closer proximity to the alluvium. Unlike the Turukku’s sedentism, the Mesopotamian author’s impression of the Kakmum people was as a dangerous and nomadic warrior people engaging in raids and attacks. After the final references to Kakmum during the Old Babylonian king Samsu-Iluna’s reign, the historical record is silent until Sargon II’s series of campaigns into Iran. In addition to the descriptor of Urartu as the land of Kakmê in the Letter to Aššur, three other texts use the term, apparently adopting their Mannean allies' name for the polity. As occupants of areas originally adjacent to the proposed Kakmum lands, the Manneans may have had ancestral familiarity with the people of Kakmum. If the people of Kakmum resided nearby Muṣaṣir and migrated to Lake Van, the Manneans may have used the archaic term for the Iron Age kings. However, this interpretation relies on the scant evidence regarding the use of the term, constrained only to Sargon II’s reign and lacking any context of Mannean toponymic etymology.

If the Urartians did not originate in the area surrounding Muṣaṣir but rather expanded from an ancestral homeland around Lake Urmia, the reasons for Ḫaldi’s position at the head of their pantheon are less clear. The apparently deliberate elevation of the god suggests the Urartian kings chose the deity for some reason, possibly his ethnic associations, location of the cult center, or the existing trans-national worship. Despite Ḫaldi’s importance in the Urartian religious and imperial system, he emerges only under the dynasty’s third recorded king, Išpuini, son of Sarduri (Salvini 2008:95). Mirjo Salvini (1987, 402; 1989, 83–85) proposed that Išpuini intentionally initiated Ḫaldi’s worship alongside Urartu’s imperial expansion. Although Sarduri’s corpus is limited to two texts neither mention Ḫaldi nor other gods, leading to the theory that the quantity of references to Ḫaldi in Išpuini’s texts indicates the deity’s likely introduction to Urartu (Diakonoff 1981, 82; Kroll et al. 2012, 28). Ḫaldi’s introduction into the newly formed Urartian religious pantheon as its paramount deity coincided with Urartu’s expansion into a transnational and ethnic state, its border expanding far south to the Ushnu plain, across the Zagros Mountains from Sidekan. Muṣaṣir’s relationship with Ḫaldi and the Urartian suggest a preexisting Ḫaldi cult with Urartian kingship inexorably altering the development of the kingdom and region.

Two inscriptions from the dual reign of Išpuini and his son Minua, the Kelishin Stele and Meher Kapisi, illustrate the process of Ḫaldi’s elevation to the head of the pantheon. The Kelishin Stele contains a dedication to Ḫaldi and a description of Išpuini and Minua’s journey to Muṣaṣir to present the god with offerings (Mayer 2013, 46). Its invocation of Ḫaldi’s wrath on whoever disturbs the stele as the primary god presents evidence for the god’s newfound importance. More directly, the Meher Kapisi inscription, a text at an open-air sanctuary near the Urartian capital city of Tušpa, lists sacrifices to the entirety of the Urartian pantheon in order of importance (Diakonoff 1983, 191–93). The order and quantity of offerings to each god established the ranking of each deity. This text, erected after the events in the Kelishin Stele, establishes Ḫaldi as supreme among the newly minted fraternity of Urartian gods (Salvini 1994).

While neither text confirms Ḫaldi’s elevation began under Išpuini and Minua, the archaeological evidence paralleling their expansionary campaigns establishes the Urartian royalty’s newfound access to Muṣaṣir. Inscriptions bearing the dual names of Išpuini and Minua record the erection of fortresses like Qaletgah and Qaleh Ismail Aqa on the north and western shores of Lake Urmia (Salvini 2004, 65–67). The creation of these fortresses was contemporaneous to the writing of the Meher Kapisi text, which Salvini (1994) sees as the initiation of an imperial religious system.

Ḫaldi’s elevation as the supreme god in the pantheon corresponded to a deliberate propagation of Urartian religious hegemony over subdued domains. As the Urartian kings expanded their territory, they colonized newly conquered areas through an elaborate network of fortresses (Smith 2012, 41–42; Earley-Spadoni 2015). Unique among the states and conquerors of the Ancient Near East was the Urartian erection of near-identical susi temples to their supreme god in each territory, imposing their religion as part of their hegemony. In addition, the Urartian state apparatus supported the religious complexes of Ḫaldi temples in Urartian towns and fortresses, as opposed to the thriving temple economies common in Mesopotamian cities (Diakonoff 1983, 303; Salvini 1989, 86; Petrosyan 2004, 6).

While aligning historical events with archaeological dates can be problematic, the data from Mudjesir excavation may contain evidence of the founding of the Urartian religious system. The radiocarbon date of the charcoal in Mudjesir’s drain dated from 895-833 BCE (Chapter 5). As discussed, the old wood problem in radiocarbon dating results in dates that often predate the actual use and burning of the carbon material by decades. Contextually, the drain’s use for emptying water would presumably wipe away small charcoal remains like the recovered sample. Thus, usage of the drain ended sometime in the mid to late 9th century. That data point provides an indirect connection to Išpuini and Minua’s pilgrimage. However, the cessation of use for the drain suggests either abandonment or construction of a new building. Abandonment is unlikely, given the Kelishin Stele’s emphasis on Ḫaldi and Muṣaṣir and the homogenous stone fill suggests a foundation or platform at the site. Instead, the termination of the drain may indicate rebuilding of an existing temple, present before the rise of the Urartian state and concurrent to the occupation of structures at Gund-i Topzawa East.

Assuming the accuracy of the above interpretation provides insights into the beginning of the Urartian Ḫaldi cult and the preexisting worship of the god in Muṣaṣir. The excavations and survey in Sidekan add the possibility of construction activity concurrent to the journey commemorated in the Kelishin Stele. The bilingual inscription notes they placed a shrine for Ḫaldi on the road and erected the inscription. Although there is no evidence for the type of shrine constructed, a structure comparable to Meher Kapisi is a tempting parallel. A later line also describes placing a “tūru” in front of the gate of Ḫaldi. Although the meaning of tūru is unknown, the gate of Ḫaldi may refer to the main temple in Muṣaṣir, raising the possibility of Išpuini and Minua’s construction or reconstruction of an existing temple. Reference to two statues in the Letter to Aššur also suggests the construction or rededication of the temple. A bronze statue of the king of Urartu praying and the copper statue of a bull, cow, and calf were both inscribed in honor of Sarduri, son of Išpuini. As there is no Urartian reference to a son of Išpuini named Sarduri, the logical conclusion is that the Assyrian scribes switched the patronymics on the looted statues. These objects likely accompanied the pilgrimage and elevation of Ḫaldi by Išpuini and would support a rebuilding or remodeling of the existing Ḫaldi temple.

While the Kelishin Stele’s mention of a Ḫaldi temple at Muṣaṣir established an existing temple in the kingdom, the archaeological evidence suggests a monumental structure at the location. The Assyrian references to a holy city reinforce a burgeoning and powerful cult before the growth of Urartu. Mudjesir’s drain’s possible association with a temple or another cult-related structure alludes to a divine municipality existing at least by the mid 9th century. Radiocarbon dates from Gund-i Topzawa East establish the region was occupied at least centuries earlier, in the 13th century BCE. The Middle Assyrian campaign texts of Adad-nirari I, Shalmaneser I, and Tiglath-pileser I provide early connections between Muṣru/Arinu and a holy city, a strong indication of cult activities in the area centuries before the rise of Urartu or Na’iri. Two Middle Assyrian personal names from the 13th century, Kidin-Ḫaldi and Ṣilli-Ḫaldi, contain the theophoric element of the god, despite the absence of references to Ḫaldi or any specific deity in the accounts of the royal campaigns against Muṣru (Finkelstein 1953, 115).

Before Išpuini’s pilgrimage to Muṣaṣir and concurrent to the radiocarbon date of the Mudjesir drain, the kingdom sent envoys to attend Aššur-nasirpal II’s festivities at Kalhu (883-859 BCE). Thus even before the Urartians elevated Ḫaldi, the god and his residing kingdom held some notoriety in the region. Even after the Urartian adoption of Ḫaldi, non-Urartian regions worshiped or revered the god. Neo-Assyrian personal names, beginning in the 8th century and continuing to the 6th century, continue the tradition of including Ḫaldi, as the god’s name prefixed at least ten individuals in texts of the period (Chapter 2). To the west, Ḫaldi’s name appears in Aramaic on the Bukan stele, part of Mannea, although chronologically concurrent to the deity’s importance in Urartu (Fales 2003, 136–38). Ḫaldi and Muṣaṣir were not, therefore, uniquely associated with Urartu. Their rationale for elevating Ḫaldi may lie in the god’s ethnic association or his association with many neighboring cultures.

A possible rationale for Išpuini’s selection of Ḫaldi as the supreme deity was not a shared ancestral connection but a connection between the god and the Urartian ruling elite’s Hurrian ethnicity. The shared etymology of Urartian and Hurrian suggests the ruling class belonged to the same ethnicity or originally migrated from similar regions. While Salvini (1995, 26-27) raised the possibility that the root of Arame’s name indicated the ruling class merely adopted the language in their role as conquerors, their cultural associations support a Hurrian connection. The second and third-ranked gods in the religious hierarchy, codified at Meher Kapisi, are the major Hurrian gods, Teišeba, the Urartian spelling of the Hurrian storm god Tešup/Teššub, and the sun god Shiuini, Hurrian god Simigi (Salvini 1995, 187). Shiuini’s consort, Tušpue, was associated with the Urartian capital Tušpa, where her cult center was likely based (Salvini 1995, 187). However, Ḫaldi’s Hurrian connection is dubious at best. The deity’s name is not of Hurrian etymology, and Ḫaldi’s name does not appear in any Hurrian texts from the second millennium, in either the Hurrian or derivative languages like Hittite (Salvini 1989, 83). Despite that, Ḫaldi’s name occurs alongside Assyrian or Aramaic. Furthermore, the name of Ḫaldi’s consort does not assist in the etymological study, as she was named Bagbartu by the Assyrians or Arubani by the Urartians, mirroring each language’s linguistic origins (Kroll et al. 2012, 29).

Apart from the association of Ḫaldi with the Urartian pantheon, a link between Ḫaldi and Mithra/Mitra provides the most substantial evidence of Ḫaldi’s Hurrian origin. Armen Petrosyan (2004) argues for the shared origins of Ḫaldi and the Armenian deity Mithra. Among the reasons is the name of Meher Kapisi, translated as “The Gate of Meher,” which directly parallels the Urartian description of the shrine in the inscription as the “Gate of Ḫaldi” (Petrosyan 2004, 1–2). Ḫaldi’s evolution and merging with Meher is further confirmed by the description of Meher Kapisi on the “Raven’s stone” in the literary Epic of Sasun, describing the origin of Meher. A seal of Urzana describes Muṣaṣir as “the city of a raven,” directly merging the two deities' iconography (Radner 2012:247). Petrosyan argues that Meher and Mitra refer to the same deity, Mithras/Mitra of the Achaemenid and Roman periods, observed through early 1st millennium CE synchronizations and similar characteristics (2004, 2–3, 6–7).

An Armenian connection to Ḫaldi is intriguing, as the geographies align within the extent of Hurrian ethnic areas but do not reveal the god's original characteristics. However, the conflation between Classical-era Mithras and Ḫaldi connects Ḫaldi to the Mitanni god “Mithra.” Mitanni, an ethnically Hurrian group with an Indo-European ruling class, associated with horse-riding in the second millennium BCE, originated and migrated from somewhere east of Mesopotamia, possibly from around Lake Urmia. If so, Ḫaldi and Mithra/Mithras may refer to the same god or share common origins at the root of the Hurrian group. The archaeological evidence for Muṣaṣir’s rise and growth in the mid to late second millennium provides an additional data point, as those years parallel the migration of Hurrians into Mesopotamia. Despite that, Ḫaldi’s Hurrian origin remains obscure and ambiguous. The name of the kingdom and its people further reinforce that equivocation. The name Muṣaṣir, while Assyrian, is likely based on the descriptor of the state near the borderlands, while the Urartian title, Ardini, merely belies its religious importance. Urzana, the only known king of Muṣaṣir, lacks an Assyrian name. However, his brother’s name, Shulmubel, reflects Akkadian linguistic etymology and a certain Abaluqunu, a governor of Muṣaṣir and Tunbaun, shares the same characteristics (Collon 1994, 38). While Ḫaldi may have Hurrian linkages, the unclear associations possibly served as precisely the reasons for the Urartian kings’ choice of the god.

The ethnic ambiguity of Ḫaldi’s origins may explain his erection on top of the Urartian imperial pantheon. As neither clearly a god for the Hurrian populations nor a local god of a kingdom of such importance to challenge the central state’s authority, Ḫaldi served as a figuratively empty vessel to imbue with deliberate meaning and symbols. The Urartian kings propagated their imperial system over conquered regions, relying significantly on a uniform religious ideology (Zimansky 2012b, 102). Early Urartu, or its direct political forebearer of Na’iri, was a loosely confederated collection of polities, while the fortresses and inscriptions of the Sarduri dynasts indicate direct control over the entire realm (Bernbeck 2003, 274–79). The emergence of the imperial authority coincided with the birth of a codified Urartian pantheon. The list of gods at Meher Kapisi includes the powerful Hurrian deities as well as a list of small regional gods, a sign of Išpuini’s intention of integrating the empire’s broader religion into one central system (Zimansky 2012b, 105–7). Ḫaldi’s pre-existence, possible importance, and geographic proximity to a large swatch of recently annexed lands made him ideal as the primary deity of this newly established religious ideology. References to Ḫaldi before this time denote his minor importance, allowing Išpuini to fully claim authority from the god while preserving the perceived independence of Ḫaldi and his associated religious economy. The lesser status of Ḫaldi, without preexisting relationships, enabled the Urartian kings to imbue meaning on their newly adopted protector.

The kings of Lake Van required a major god to support their expansionary ambitions and provide supernatural legitimization for their actions, as the Assyrians had with their supreme deity Aššur (Zimansky 2012:105). Ḫaldi’s introduction in Urartu served that purpose and validated the aspirations of the Urartian kings (Salvini 1989:80-81). The Urartians could not simply claim ownership of a major god comparable to Aššur, like Teššub, and thus seemingly conjured a supreme god of their own. The contrast between Ḫaldi’s previously minor importance and explicitly royal symbology supports their deliberate assignment of characteristics. Discussed in the context of the temple on the Khorsabad relief, common motifs of Ḫaldi include spears, shields, lions, and warfare (Loon 1991, 20; Belli 1999, 37–41; Zimansky 2012a; 2012b, 105–7). Ursula Seidl (2004, 199-200) notes that these symbols and the representation of Ḫaldi on the Anzaf shield directly parallel the imagery of Ninurta and Nergal, Assyrian deities associated with kingship. Nergal specifically confers the Neo-Assyrian kings the weapons for their conquests, much like Ḫaldi’s spear does for the Urartian kings (Cassin 1968, 72). Ḫaldi’s suspicious association with the royal gods of Assyria, despite his previously obscure status, argues for Urartian assignment of kinglike characteristics. Further, beginning with Išpuini, Ḫaldi’s name appears first in indexes of gods, even as the minor deities vary depending on the location of a given text (Zimansky 2012:106). The continuation of local worship while simultaneously imposing adoration of an imperial god is a common trait of imperial expansion.

Studies of empire and imperial expansion note how ideology can serve to justify imperial expansion and how conquering forces often appropriate deities of conquered populations in the pursuit of control (Carneiro 1992, 193–94; Schreiber 2008, 131). A commonly observed behavior is the creation of new religions around the king or emperor then imposing that system on subdued populations (Sinopoli 1994, 168). Even though leaders seize the legitimacy of existing ideologies, the appropriated symbols grow in importance and merge with the political reality of the appropriator (Sinopoli 1994:167). Areshian (2013, 6) lists five methods of imperial integration, including oppressive domination of populations and incorporating local elites into institutions, a combination of two that best describes the Urartian empire. Through the context of trends in imperial expansion and ideology, the appropriation and propagation of Ḫaldi is unremarkable. However, while Muṣaṣir’s material culture reflects Urartian traits, the kingdom was never fully conquered and integrated into Urartu. Even Rusa S’s reconquest and occupation of the kingdom’s cult center lasted only 15 days and ended with Urzana’s reinstatement on Muṣaṣir’s throne. This exact situation is rare for the major empires of the world, who seemingly choose to elevate conquered gods within their direct sphere of control. Even the elevation of Marduk to the top of the religious pantheon of the Babylonians began when Babylon was the political capital of the Old Babylonian state. Although Marduk’s worship and position at the top of the pantheon occurred during the reign of the foreign Kassites, his cult center at Babylon fell within the core of Kassite territory (Tenney 2016).

By keeping the cult center outside of the empire's borders, the kings may have gained an air of legitimacy from an apparent degree of independence, as opposed to a god residing next to the king’s residence. A second Urartian-style susi temple alongside the existing Muṣaṣir Ḫaldi temple may have been an effort to connect the Muṣaṣirian Ḫaldi cult to the Urartian imperial religious ideology without direct control of the kingdom. The visibility to people on the Iranian plateau and Mesopotamia further cemented the god’s supposed independence. Muṣaṣir’s borderland status corresponds to the god’s marginal identity, ready for adoption (Radner 2012, 247–48). Compare the situation of the existing supreme Hurrian god. The primary temple of Teišeba, the second-most important god in the Urartian pantheon and first among the Hurrians, was also outside the borders of Urartu, in the southern borderlands of Anatolia’s Taurus Mountains (Radner 2012, 254–56). However, Teišeba’s existing identity and independence likely complicated cooption by Urartian rulers and endowed too much Hurrian character on the religious ideology.

The final question of Muṣaṣir and Ḫaldi’s origin concerns the god’s genesis, when the deity first emerged and became associated with this area. A dearth of early religious architecture and scant remains from Sidekan’s Late Bronze Age limit any insights about the nature of Ḫaldi’s worship before the 9th century BCE. Thus hypotheses must rely on historical or environmental data. Petrosyan’s historical linkage of Ḫaldi and Meher leads him to argue that the Urartian god shared several common characteristics, including emergence from the ground and caves (Petrosyan 2004, 6). Caves also relate to the Nestorian epic of Mar Qardagh, where Qardagh travels to Beth Bgash, in the “upper reaches of the Great Zab River and Lake Urmi[a]” (Walker 2006, 166). One hypothesis, therefore, was that the existence of caves in the area sparked the proverbial birth of Ḫaldi. However, the area around Sidekan and Mudjesir has no documented caves, despite the preponderance of the geological structures to the west and north. The geological characteristics of Sidekan, with folded igneous rocks creating dendritic drainage networks, are subpar conditions for natural stone cavities, as opposed to the karstified limestone of the Baradost Mountain west of Soran (Solecki 1998, 26; Sissakian 2013).

Sissakian’s geologic map of northeast Iraq indicates that Sidekan is the least likely location for cave formation. In addition, the association with caves relies primarily on the connection between Ḫaldi and Meher. While the “Gate of Ḫaldi” at Meher Kapisi may relate to caves, more common motifs include fire, fertility, winemaking, lions, bulls, a spearhead, or a raven (Petrosyan 2004, 4–5; Zimansky 2012b, 103–5; 2012a). Associating these motifs with Sidekan is an exercise in pure speculation or extrapolation from minuscule modern details, such as using the existence of a few small vineyards in Sidekan as proof as a connection. Future research in Sidekan or the exposure of additional texts related to Ḫaldi may establish further characteristics about Ḫaldi or his predecessor. Until that time, the current dataset established Ḫaldi’s longevity and adoption by the Urartians as a symbol of their imperial dominion.

Conclusions

The history of Muṣaṣir demonstrates how the intersection of technological, religious, and cultural factors affects a marginal region's growth in positive and negative trajectories. The technological innovation of horse transport initially spurred the growth of Muṣaṣir’s sedentary occupation. Either alongside that phenomenon or because of it, the cult center of Ḫaldi in Muṣaṣir led to the kingdom’s increasing importance and visibility, even as it maintained independence. With the selection and appropriation of Ḫaldi as the preeminent god of Urartu, Muṣaṣir effectively became a client state of the kings of Van but without the direct support or control of regions under the imperial hegemony. The Urartian cooption of the god ensured that with the empire’s fall, the assistance and support the kingdom enjoyed would end. Without the artificial assistance of their Urartian benefactors, the settlements in Sidekan could not support the density of occupation in the Iron III. Thus, while the original catalyzing force of improved transportation in the area enabled growth, the cultural focus led to a decreased overall occupation in the long term.