As a part of the larger Rowanduz Archaeological Program (RAP), the objectives of the Sidekan survey were to gain an understanding of the types of settlements in the accessible areas of the subdistrict and determine the chronological extent of occupation. These data informed RAP’s overall goals of establishing a diachronic sequence in the region and investigating agricultural land use. In addition, survey activities in the Topzawa Valley planned to document partially damaged sites along the road cut, noting architectural features and ceramics comparable to the excavated occupation at Gund-i Topzawa. The survey of the Sidekan subdistrict occurred primarily in 2014 and 2016, with the 2013 season limited to recording previously documented sites from Boehmer and Fenner’s (1973) project. Due to the survey project’s absence of an independent budget and staff, the survey methods, amount of time, and team size were ad-hoc and inconsistent between seasons and days. For example, while the 2013 and 2014 seasons occurred during the summer, the 2016 season primarily took place in October. However, I was present for all but one of the survey excursions, often accompanied by other RAP team members or employees of the Soran Department of Antiquities. While the inconsistent survey timing and methods provide difficulties in making direct comparisons between sites using the available data, my recollection is intended to bridge some of the recording gaps.

Conducting this survey in Iraqi Kurdistan during 2013 – 2016 came with a set of challenges and constraints beyond the control of the project. Chapter 3 reported on the difficulties and lengthy period to obtain the excavation and survey permit. Fortunately, the permit’s broad mandate for survey allowed work across the Rowanduz, Diana, and Sidekan subdistricts. However, external geopolitical events constrained the projected further, beginning with ISIS’ occupation of Mosul in 2014 that, in addition to the immediate humanitarian crisis, constrained our ability to move around the area. In 2017, the Iraqi Kurdish referendum on independence and the subsequent closure of the Erbil airport by the central government halted plans to return for fieldwork (Zucchino 2017). Throughout the project, the presence of two foreign Kurdish militant groups operating cross-border activities – the KDPI, from Iran, the PKK, from Turkey – limited survey and travel of the Sidekan subdistrict to only the valley systems directly adjacent to Sidekan, Topzawa, Bora, and Hawilan Basin (Figure 1.1).

While Chapter 1 introduced the geographical background of the region broadly and the Sidekan subdistrict specifically, dividing the subdistrict into smaller graphic units highlights their topographical differences and assists in the discussion of site locations (Figure 5.1). The accessible and surveyed subareas are Mudjesir, Sidekan, Topzawa Valley, and Hawilan Basin. In addition, the so-called “Old Sidekan Road” serves as the shorthand for the land alongside the Sidekan and Barusk Rivers, starting at Shiwan and extending eastwards to Shakh Kiran Mountain. Sidekan and Mudjesir form the core of modern occupation (Chapter 4). Sidekan’s optimal settlement positioning is due to its location on the 4 km wide plain at the confluence of the Topzawa, Bora, and Zanah Rivers. Mudjesir’s advantage derives from its adjacency to Sidekan and position along the route towards major population centers to the west. The Topzawa Valley follows its eponymous river almost 10 km from the eastern extent of Sidekan up to the ascending peaks of the Zagros Mountains chaine magistrale. The Hawilan Basin is the elevated northern slopes of Hasan Beg and Musa Kawah Mountains. The paved new Sidekan Road descends from the pass adjacent to Hassan Beg Mountain down to Mudjesir, including the area south of the Sidekan River. The Old Sidekan Road largely follows the path of the Sidekan River descending through the mountains as it becomes the Barusk River.

Additional subareas warrant mention, although we did not have the opportunity to travel to those areas. These include the Nazar Basin, Senne Valley, Bora Valley, the Kelishin Pass, and the many high mountain peaks in the area. The Nazar Basin extends approximately 14 km north of the Barusk River to the inaccessible valleys of Barasgird and Kwakura, and 20 km east-west, bounded on its eastern border by Shakh Kiran Mountain and its western border by multiple peaks, including Sari Mountain. The Senne Valley is a narrow valley comprising an eponymous river with little farmable land on its sides. Before constructing the road along the Topzawa Valley, one of the primary routes for reaching the Kelishin Pass. The Bora Valley runs roughly parallel to Topzawa, although its headwaters do not lead to the Kelishin Pass. Accessing the Kelishin Pass was impossible due to our political status and the dangerous terrain.

Methodology and Methods

Locating and recording archaeological material culture and sites are the primary functions of site-focused survey projects. The methodology of locating archaeological material and sites generally fall under two categories: intensive and extensive. While extremely reductive, intensive survey looks intensively “down” at the surface for artifacts indicative of archaeological occupation, and extensive survey looks broadly “outwards,” searching for indicators of archaeological sites. While neither method is inherently better or worse, the history of archaeological survey moved from using exclusively extensive techniques to intensive survey with increasingly small scale and units of observation. Extensive survey includes reconnaissance, searching for sites at a large scale – often using vehicles or remote sensing – and pedestrian extensive survey. Early archaeological survey projects employed extensive methods almost exclusively, often using vehicles to traverse the landscape to find the locations of clear topographic features, like archaeological mounds (Adams 1981; Braidwood 1937). While sufficient for locating large or obvious sites like the mounds of the Near East, that method of surveying was insufficient for other regions with more concealed archaeological remains like the regions surrounding the Mediterranean Sea.

Intensive survey methods use pedestrian survey for locating individual artifacts, using techniques like field transects or small subdivisions of the landscape like collection grids (Orton 2000). In contrast to extensive survey, artifacts serve as the primary data point for intensive survey, usually using the distribution and density of artifact scatters as a proxy for a site. Given the effort expended per m of the survey area, most intensive survey projects cannot completely cover their project area. Landscape archaeologists developed statistical sampling methods of drastically differing complexity that enabled analyses for entire areas using only a small subset of spatial coverage (Banning 2002, 7; Collins and Molyneaux 2003, 6). Using the artifact as the core data point for sampling, archaeologists could use a small sample of all possible data to make conclusions about the site and regional relationships (Binford 1964, 429–35). In study areas with fewer artifacts or obscured sites, intensive surveys with sampling enabled further conclusions about the extent and nature of settlement.

Extensive surveys in the Mediterranean, like that of Messenia in Greece, were successful in locating hundreds of sites in their survey area, but the conclusions following the recorded data, such as the size of communities or occupation, were revealed as incomplete when followed by intensive survey projects (McDonald and Rapp 1972). The Messenia survey, for example, located sites using topographic features of known Mycenean era sites as a guide. However, a project with intensive survey methods in the succeeding decades located eight times the number of sites and resulted in a changed understanding of the types of sites – specifically small sites originally interpreted as farms (Bintliff et al. 1999, 141–2).

While intensive methods enable new analyses, including detailed taphonomic studies concerning plowing’s effect on site recovery and surface visibility of sherds, as well as the finer scale of detail about settlement patterns, archaeologists did not abandon extensive survey (Ammerman 1985; Dunnell and Simek 1995). Some practitioners put forward a notion that greater intensity of survey recovery leads to improved outcomes, but tests of the low density, extensively survey sites of the Near East indicate extensive survey may be sufficient for many projects or regions (Cherry 1983; Wilkinson 2004). Further, the divide between extensive and intensive survey may not always be clear-cut. For example, in the highland Amuq Valley Regional Project survey, they spaced their transects 100 m apart but noted while they considered the survey intensive, many Mediterranean archaeologists would consider the project “semi-intensive” because of the large unsurveyed spaces between transects (Casana and Wilkinson 2005, 27). Factors such as the size of the total sampling universe, the morphology of sites, mode of surveyor conveyance, and site definition often serve as the primary dimensions for defining a survey as intensive or extensive (Hammer 2012, 170).

This following slightly exaggerated example best illustrates the difference and overlap between the two methods: a surveyor begins engaging in extensive survey driving on a road in southern Mesopotamia, locates a large mound in the distance, and then intensively surveys the surface of the mound on foot using transects or collection units divided into equally sized grids of 10 x 10 m. The fictional surveyor’s use of extensive and intensive techniques reinforces that these methods are not mutually exclusive or in opposition to one another. In recording sites and materials, the question arises, what is the entity discussed in the surveyor’s notebook?

A key part of survey is defining a site, necessary for the practical purposes of recording and analysis of collected material as well as interpreting the significance and implications of the data. While over the last century archaeologists’ definition of the word has evolved significantly and gained progressively more specificity, the competing definitions of site fall along two opposite poles: at one end is the view of the site as a “discrete and potentially interpretable locus of cultural materials,” with boundaries around those loci (Plog et al. 1978, 389). The opposite pole sees the landscape as a continuous and varied surface of human occupation, with concentrations of artifacts or landscape features serving as data points indicating the extent and type of human interaction (Dunnell and Dancey 1983).

The chronological evolution of the term site helps explain the current perspectives of the terminology. The usage of the word in archaeological contexts began in the early 20th century. Preoccupation with monuments, predating the beginning of any archaeological research, began evolving to encompass a wider variety of archaeological material, including monuments along with cities, villages, or collections of artifacts. Robert Dunnell (1992, 22) described this early terminology as “a place where something else, be it artifacts or monuments or a combination of the two, occurred.” Over the succeeding decades, scholars utilized the term without fully defining its usage, utilizing ‘site’ as the catchall term for archaeological loci of some activity. By the mid-20th century, scholars attempted to define and provide the factors in what they previously took as implicit. Frank Hole and Robert Heizer (1969, 14) put forth one definition, stating, “a site is any place, large or small, where there are to be found traces of ancient occupation or activity.” Gordon Willey and Phillip Phillips (1958, 18) advanced a similar definition, indicating that a ‘site’ is “the smallest unit of space,” for which limits “are often impossible to fix,” and must be “covered fairly continuously.” While only moderately more specific than their earlier counterparts, one sees the beginning of an evolution away from the site as a discrete unit towards something defined by artifacts and with ambiguous boundaries focusing on observation of material.

Out of the “New” (or Processual) Archaeology school emerged the concept that scientific methods governed archaeological processes. Lewis Binford (1964, 432), a leading voice in this movement, viewed ‘sites’ as “a spatial cluster of cultural features or items, or both,” and that cluster may or may not be homogenous (Dunnell 1992, 24). In Binford’s view (1962), sites are products of the behaviors of past peoples that follow laws governing human activity and are not defined solely by the existence of features or artifacts. As the deposition of artifacts follows certain processes, it was not necessary to find every possible artifact to make conclusions, but systematic sampling of areas could reveal characteristics of the past. Thus, by only intensively surveying a small selection of a given survey area and following scientifically rigorous sampling methods, surveyors could generate conclusions about the totality of the zone – the conceptual birth of intensive survey (Collins and Molyneaux 2003, 6). Binford raised the artifact as the base unit of observation to be used in large regional and small localized surveys (1962, 429–431). Using artifacts as the unit of observation, sites are comprised and defined by concentrations of artifacts and their spatial relationship.

Another wave of archaeologists moved away from the concept of the site as a unit of measurement at all, focusing on the idea of siteless survey. Once artifacts became the primary unit of measurement, a survey area becomes a continuous surface, with sites the “foci of surface artifacts” relatively dense by comparison to the background level (Bintliff et al. 1999, 142). Rather than calculations or intuition of density to the “non-site” background areas, siteless survey attempts to remove the concept of the site altogether. In that framework, a site no longer consists of the base unit of measurement, an artifact, but archaeologists simply collect and analyze the distribution of artifacts (Dunnell 1992). While practical matters arise when recording every artifact individually and analyzing that quantity of data, the non-site approach denotes the apex of the evolution of a site’s definition – away from the site altogether.

A further aspect of a site’s definition that impacts the analysis of collected material is the ontological basis of a site. In that, archaeologists must answer if a site represents an immutable unit, parallel to some bounded spatial extent by the previous inhabitants or creators of a site, or simply an observed collection of artifacts or features, completely created by the archaeologist at the moment of its observation. Non-definitions of site in the early 20th century believed, at least implicitly, sites were ancient units waiting for discovery, existing outside their own observations. However, modern archaeological theory is unified in the understanding that sites are “synthetic constructs created by archaeologists” (Goodyear et al. 1979, 39). Despite the acknowledgment of that fact, many struggle with the inherent contradictions in language that sites’ ephemerality create. For example, one page after acknowledging that sites are synthetic and created by archaeologists, the authors of the above quote state that sites are “encountered” or “discovered” (Goodyear et al. 1979, 40). If archaeologists create sites, they can never be discovered, as discovery is dependent on the pre-existing nature of something.

The many definitions of site and language associated with site survey naturally lead either to a never-ending increasing specificity of density or the abolition of the term completely in favor of artifact collection. The surveyors chosen scale of recording implicitly constrains the site’s definition to the collected data types. When a project defines a site as the base unit of measurement, the determination of a site is solely based on individual conceptions of a site. If, instead, a site consists of smaller units of measurements, like lithics or individual ceramic sherds, a site’s definition relies on the spatial extent, quantity, and boundaries of artifacts. While scores of scholars offer exacting definitions or formulas to provide a universal or near-universal understanding of the word “site” in the context of survey, they all fall victim to the unavoidable differences across projects and regions. Rather, defining a site is not a universal task but a necessary definition for each survey project to present biases and transparency.

RAP’s site definition for the Sidekan subdistrict survey is best defined as a convenient linguistic construct for a “unit of collection” that does not necessarily correspond to some discrete, preexisting structure or entity. The word convenient acknowledges the reality that site determinations were done due to the many constraints of fieldwork, not as an indication of archaeological significance. Some sites, like Gund-i Topzawa, were recorded as one site when an equally logical division would record each visible building as one unit. Other sites, like Melesheen, discussed below, were divided as different sites based on modern fields. That division existed solely to differentiate the location of collected pottery. Equally justifiable would be a single site that included all the fields with bags specifying findspots. The following Site Description section attempts to explain the limits and definition of each of these sites. Individual sites, denoted by the recording convention of “RAP##” (e.g., RAP30), do not have significance and should not be directly compared without knowledge of their characteristics.

How then did RAP locate these varying types of these so-called units of collection? Given the constraints of the project and the landscape, we employed several methodologies that do not fall neatly under the framework of intensive and extensive survey. They included reconnaissance – often driving to areas and led to archaeological sites by locals – extensive pedestrian survey, and intensive pedestrian survey around areas of interest. By far, the most effective method of site prospection involved direct intelligence of known sites or material. Material from Boehmer’s publication (1973) provided significant assistance in locating resurveyed sites, as the landscape was altered in the intervening decades. Extensive pedestrian survey primarily consisted of walking areas with expected archaeological material. The hills around Mudjesir and the length of the road cut along the Topzawa Valley were two examples of this type of survey. Our intended unit of collection for this method of survey was a site, not individual artifacts. The final method involved intensive pedestrian survey around areas of known or suspected archaeological activity. The intensive transects nearby Sidekan Bank were an example of this method (Chapter 4). This technique’s intention was to record individual artifacts and their positions with sufficient spatial specificity.

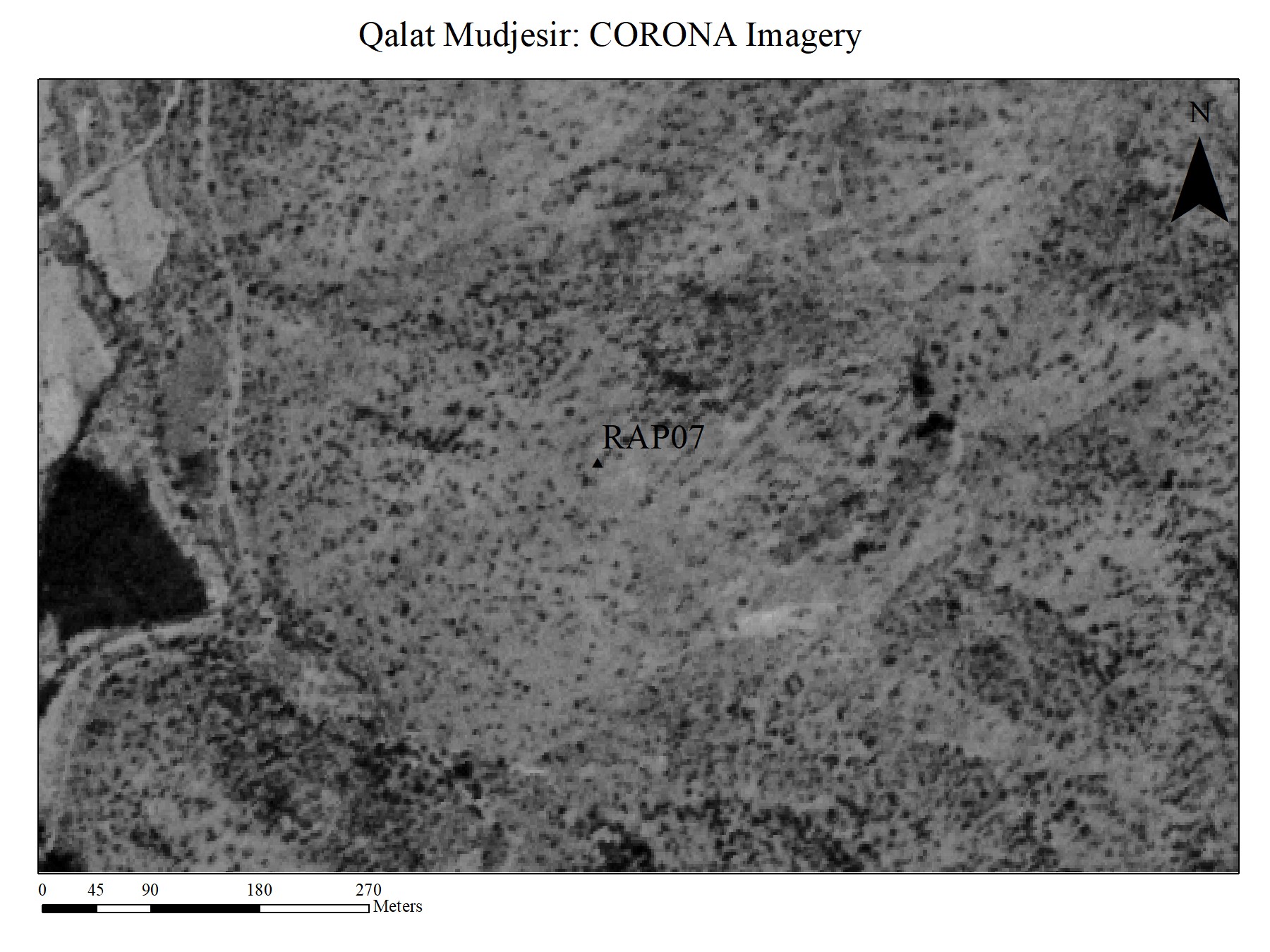

These three methods did not use one of the most utilized and successful site prospection tools of the last two decades – remote sensing. The increased use of high-resolution and multispectral satellite imagery and the greater accessibility of historical aerial photographs transformed many survey projects, with remote sensing analysis and site location preceding most ground-truthing fieldwork. Projects in northern Syria and southern Turkey pioneered the use of CORONA imagery to locate mounded archaeological sites or ancient features like canals or hollow ways, using discoloration and pattern identification and analysis associated with pre-modern alterations of the landscape (Casana 2013; Casana and Wilkinson 2005; Ur 2004; Wilkinson et al. 2004). Satellites in the 1960s and 1970s captured CORONA imagery from before modern agriculture and urban development altered the terrain to its current state, enabling analyses impossible with modern satellite imagery. Even in areas well suited for this type of remote sensing, the image quality and capture season can yield drastically different levels of effectiveness. With higher resolution imagery, remote sensing projects flagged features like roads, hollow ways, and stone constructions, for example (Hammer 2012, 181–185). While utilizing those remote sensing methods, RAP’s survey project and the Sidekan survey found them largely ineffective for detecting known and unknown sites, a phenomenon also observed and discussed by adjacent contemporary survey projects.

In the 2014 and 2016 seasons of UZGAR, surveying the valleys and piedmonts nearby in the district west of Soran, the surveyors reported difficulty in ground-truthing areas identified using CORONA or GeoEye-1 satellite images (Kolinski 2016). Visual characteristics that proved successful in identifying mounds or mudbrick in that project’s survey of the adjacent Navkur Plain were natural features in the valleys around Zur-i Purat and Dasht-i Harir. Specifically, lighter spots on the image, generally indicative of mudbrick on the plains, were usually stone concentrations of pebble or exposed bedrock and shadows from the naturally rugged landscape obscured the characteristic shadow marks, often cast from high mounded settlements (Kolinski 2014). Although discussed in less detail, the Khalifan survey had similar difficulties, with satellite imagery primarily leading to preserved stone settlements on promontories (Beuger et al. 2018).

While CORONA imagery proved ineffective for site prospection in Sidekan, two CORONA images (1104-2138 aft and 1107-2170 aft) covered the area with sufficient quality to assist in non-prospection related research questions. The images were captured on August 16, 1968, and August 3, 1969, respectively, and georeferenced in ArcGIS to compare any landscape changes before the military occupations beginning in the 1980s. The images proved useful for understanding the urban expansion or construction in the past fifty years and flagging contemporary inhabited areas that may cover areas of interest for archaeological prospection.

Modern imagery was largely restricted to Maxar/DigitalGlobe, available freely through Bing Maps and ArcGIS Pro, as Google Map’s coverage of the area often consists of outdated and low-resolution imagery. The imagery’s resolution was sufficient for identifying small features on the landscape, but, like the surrounding mountain survey projects attested, archaeological sites in Sidekan do not leave distinct patterns detectable in the imagery. For identifying characteristics of archaeological sites reflected in the imagery, Autoclassification was not possible due to the number of sites and their heterogeneous taphonomic types (i.e., buried and cut at the base of the valley vs. hilltop fortresses). Maxar imagery is restricted to the visible bands of light. After 2016, I analyzed multi-spectral imagery types (Sentinel, Hyperion, and Landsat 8), but the efficacy of that imagery for site prospection cannot be determined without grounding truth points of interest. While multi-spectral imagery of this type is useful in analyzing the modern landscape for soil health and the extent of agriculture, its efficacy for reconstructing past landscape is limited (Chapter 6). In addition, ASTER GDEM V3 served as the digital elevation map (DEM) for any topographic analysis.

Figure 5.1 not yet available

class="w-full max-w-3xl mx-auto border border-white/10 group-hover:border-[var(--color-brand-orange)] transition-all"

loading="lazy" />

Figure 5.1: CORONA Image of Qalat Mudjesir. August 16, 1968

(click to enlarge)

The near impossibility of identifying sites in Sidekan by remote sensing was demonstrated as early as 2013 when ground-truthing Qalat Mudjesir. Even that hilltop site, with visible walls exposed over hundreds of meters, was not distinct in either CORONA or DigitalGlobe imagery. Rather, the trenches and other alterations of the site by military occupation left clear marks visible through photographic remote sensing. CORONA imagery of the site of Qalat Mudjesir in 1969, before military modifications altered the site, show few signs of the archaeological site present (Figure 5.1). In comparison, contemporary satellite imagery of Qalat Mudjesir shows the addition of the military trenches that obscure the site’s faint wall traces and the small mound of the site’s upper building (Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.2: Contemporary Maxar satellite image of Qalat Mudjesir with military fortification trenches visible.

Other projects in the region documented how the visual characteristic of these military trenches obfuscated archaeological features (Casana and Glatz 2017, 18–20). As a coincidence of the site's topography, the trenches resemble the general layout Boehmer and Fenner published. Using remote sensing with much higher resolution, photogrammetry of the site created from flying a drone dozens of meters above, showed the walls and their debris eroding down the hillside, but again the military modifications of the site were the prevalent feature. The military trenches atop Qalat Mudjesir are a further impediment to remote sensing prospection. Many hills and mountaintops in the area exhibit the same patterns as Qalat Mudjesir, now known to be military trenches, obscuring any possible archaeological features. Further, the continued existence of minefields around previous military fortifications prevented ground-truthing of these promontories. While serving as a complementary tool to terrestrial fieldwork, remote sensing remains ineffective as the initial prospection method.

Methods

RAP’s recording methods relied on a combination of paper data entry forms, digital equivalents, and journal entries detailing the survey activities of the day. Beginning in 2014, we created a form with specific data dimensions to enable data uniformity, printed out for use in the field. The intent was to streamline the data collection process and enable other team members to survey independently. Prior to the 2016 season, I implemented a survey database, using Airtable, mirroring the fields and data collection types. A mobile app enabled the possibility of direct data collection and entry in the field, removing the additional step of entering the analog data online after the completion of surveying. Unfortunately, the limited mobile internet service and required connection to Airtable’s servers led to inconsistent use of digital recording. Given the advances in technology and connectivity since 2016, future seasons can use the fully digital recording process. The addition of excavation data to the survey database to create a “master” record makes digital-first data collection more effective and impactful, allowing for the lookup of existing data and input of different data types.

The available tools directly influenced the types of data recorded. Our primary method for recording the location of sites was a handheld GPS. The point number, stored on the GPS unit, was added as a data field for each site, with the exact coordinates recorded during laboratory analysis. In instances of sites with defined spatial limits or multiple points of interest, we recorded multiple GPS points, noting the significance or context of each point. For example, at Gund-i Topzawa, we recorded a point at each end of the furthest extent of visible architecture in the road cut. Maps of sites in the survey area use these GPS coordinates, selecting a single central point for sites with multiple recorded coordinates. Tape measures and pacing served as additional tools to estimate the size of sites or features when possible. We sketched features of interest on the paper recording form, when necessary, although photographs often provided a better reference.

Photographs of sites and their environs served as the most valuable data source for understanding and reconstructing the landscape and site distribution in the Sidekan subdistrict. Each team member took photos on their respective devices, although I captured most images with a Nikon D3500 DSLR. Lab work, at the end of the day, categorized each photograph to its respective site and saved it in relevant folders. In addition, we experimented using UAV photography to record different perspectives of the sites and create 3-D photogrammetry models. 2014’s season utilized a homemade drone with an attached Canon “point and shoot,” which failed almost immediately on takeoff. 2016 used a DJI Phantom 4 with an attached camera. We recorded only two sites, Qalat Mudjesir and Qalat Gali Zindan, using this technology. While the different perspective was useful for a broader perspective of the sites, the images did not reveal additional features or patterns in the visible material.

Artifacts associated with the sites, either ceramics or additional objects, were collected in bags, using the same recording system as the RAP excavations (Chapter 4), with survey specific bag numbers (ex. “SUR.1”) used in lieu of the printed bag tag numbers from the excavation (ex. “1010”), although they were used equivalently. Like excavation recording, a bag’s number has no significance with the context, and multiple bags may relate to one site. Each object type from a site had a unique bag number with associated object type information. Given the precision limits of the GPS, all ceramics from a site were collected into one bag. In instances where we desired additional spatial control, we created a new site designation number with associated contextual information and bags. The few sites with intensive pedestrian survey using transects noted the position of pottery using GPS points or collected pottery by its overall transect location. Given the limited collection of material, the spatial position is unanalyzed. Team members processed objects in the lab concurrently and with the same process as excavated material (Chapter 4).

In addition to the above data, the field recording forms had spaces for the surveying team to add additional information about sites. The field site type categorized sites by their visible taphonomic characteristics, for example, exposed architecture versus a field scatter. However, site types were not mutually exclusive. The visible architecture of multiple sites suggested a modern or recent date but warranted documentation if that theory was incorrect or if future research intends to utilize that information. Three fields describe the sites’ current condition: location, current land use, and visible architecture. The multiple dimensions provide different perspectives and aspects to add information regarding the visible features of the site. The “area” field resulted in extremely different data, as the drastically different types of sites yielded information that could not be easily compared across the survey. An additional field, not present on the form, was the “find method” – with options including construction, local led, pottery scatter, or already known, among others. Appendix B’s Survey Gazetteer contains the full list of available information for each recorded site.

Site Descriptions

The following section describes pertinent details from all sites surveyed by RAP in the Sidekan sub-district (Figure 5.4). Overall, we recorded 43 individual sites over 15 days in RAP’s three survey seasons, although multiple site designations (following the naming convention RAP##) are combined when appropriate. For example, the cluster of RAP sites around Mudjesir are discussed as one individual unit. As the methodology’s site definition discussion alluded to, the raw number of sites documented is not necessarily representative of the underlying settlement pattern. In at least one instance, I individually recorded four sites named Melesheen, directly adjacent to one another, while a different surveyor would be valid in collecting all as one site of Melesheen. The report of sites discusses each distinct settlement locus as one unit, regardless of the designations or subdivisions. The following sections detail each of the sub-areas in the Sidekan subdistrict, beginning with Mudjesir. The section includes resurveys of Boehmer’s fieldwork and new survey activities, as well as information regarding RAP excavations at a Mudjesir field and Qalat Mudjesir. After data on Mudjesir and additional Boehmer resurveys, the following sections detail the sites by each sub-area: Sidekan, the eastern valleys, the Hawilan Basin, and the Old Road.

Mudjesir: Boehmer Survey, RAP Survey & Excavation

Boehmer’s survey of Mudjesir and other sites in the Sidekan subdistrict briefly surveyed part of Sidekan and Mudjesir in 1971, led to this area by the published existence of anthropomorphic stone stele and the known locations of the Topzawa and Kelishin stelae (al-Amin 1952; Boehmer and Fenner 1973). He returned in 1973 with his architect colleague, Fenner to fully survey Mudjesir and surrounding areas. Their survey around the village of Mudjesir in 1973 was extensive – tracing architectural features, collecting considerable pottery, and recording large stone artifacts. The overview of the pottery typology discussed much of his pottery from Mudjesir reported by Boehmer and organized into Urartian typologies by Kroll (Chapter 5). Boehmer’s published ceramics from his 1973 survey aligns with the excavated material from Gund-i Topzawa and Mudjesir, indicating an Urartian Iron III occupation. Further surveys of the fields and hills around Mudjesir located additional sites, each recorded site representing loci of ceramics or architecture, some of which relate to areas of Boehmer’s survey. The following section reintroduces Boehmer’s work and expands on the detail from his primary 1973 report, with additional information about the known Mudjesir area sites gathered from RAP’s survey of the area. At sites where the RAP site directly corresponds to Boehmer’s original survey, the documentation describes the related material culture and surrounding landscape. Following is a section reporting on newly recorded sites by RAP around Mudjesir. Concluding the discussion of Mudjesir is a summary of unpublished RAP excavations at Mudjesir.

##### Boehmer Survey of Mudjesir

The most visible archaeological feature at Mudjesir is the site of Qalat Mudjesir, a hilltop stone structure located on one of the more prominent hills southwest of Mudjesir village. Boehmer documented 410 m of a partially preserved stone wall encircling about .93 hectares of the site (Figure 5.4). The outer wall comes to a point in the southern extent, where Boehmer believed a gate originally stood. At the site’s center, elevated from the surrounding, was a central rectangular building with outer buttressing. In total, Boehmer and Fenner recorded 17 buttresses around this building. The walls were about 2.5 m thick, although the stone was barely raised above the surrounding surface. Not far from the central building, they noted a small fragment of a rectangular wall, paralleling the shape of the central building (Boehmer and Fenner 1973, 508–510). Returning in 2013, most of the walls Boehmer and Fenner described remained visible, but the site was covered in military trenches from its use as an encampment during the Iran-Iraq War. As noted above, the trenches obscured some of the walls in satellite imagery, but the areas of the site without military trenches continued to reveal the stone walls. In 2014, the geomagnetic survey by Jorg Fassbinder and his team from Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege, Munich, confirmed Fenner’s floorplan, identifying wall features in the locations previously mapped (Fassbinder 2016, 118). However, the other conclusions from the geomagnetic survey are suspect, as the quantity of metal shrapnel on the site created several false-positive signals from the magnetometer.

Boehmer’s dating of Qalat Mudjesir relied almost exclusively on the architectural buttressing of the central building and stone construction techniques, comparable to imperial Urartian structures. Their survey of the site’s surface recovered only a few non-diagnostic sherds. While their ware was broadly similar to the many sherds located in the survey of Mudjesir, suggesting an 8th to 7th century BCE date, the forms of the vessels could not confirm that dating. The building’s structure reinforced that date, showing clear connections to Urartian architecture from sites like Bastam, Zivistian Siah, and Kale Oglu, although those structures were individual buildings in larger fortress complexes (Boehmer and Fenner 1973, 510–512). The rectangular shape and buttressing, seen at monumental halls at those sites. Discussed further in the following Mudjesir Excavations section, Michael Danti’s brief excavation of the central building did not confirm Boehmer’s dating but provides little evidence against an Urartian or 8th to 7th century BCE date.

Along with the fortified site on the hill, Boehmer’s survey recorded considerable stone architectural remains on the lower plain, adjacent to the river. He traced a significant wall in the area termed the “Lower City,” the flat areas intermixed with fields and orchards. In the 2010s, this area exhibited similar characteristics of small fields intermixed with orchards or large trees. Directly south of the Sidekan River was the wall, up to 7 m tall in sections (Figure 5.4, Wall 1). Boehmer noted the upper phases were likely relatively recent, built upon older foundations not visible from the surface. The visible courses were constructed with large fieldstones, with each course of the stone wall laid perpendicularly, alternating with long and short length stones. In the exposed wall section, he noted two angular corners, raising the possibility of a gate here, before the wall ended in the west, with the eastern extent ending near a small stream by the village buildings. Fragments of the walls continued around the village, facing the east (Figure 5.4, Wall 2) (Boehmer and Fenner 1973, 489–490). He gave no explanation for why the portion of the wall, directly facing the river, would have served as a gate. From the photographs in the publication, the type of stone construction resembled Gund-i Topzawa’s walls, with the telltale friable slate and alternating perpendicular stone courses. While accessing this area of Mudjesir was somewhat difficult with overgrowth and significant bees from the residents’ beehives, we recorded similar stone structures to what Boehmer described. Much like Boehmer noted, there was some pottery but far less than other areas of the site. However, the stone walls did not resemble fortifications, if due only to their narrowness, though the possibility exists of buried walls of greater width or that these walls were the foundation of wider features.

Boehmer followed the path of the wall, past the village’s eastern extent, to the south, where the main Sidekan road cut the hillside going eastwards. He believed the wall continued southwards, cut perpendicularly by the road construction, before disappearing into the steep hillside to the south (Figure 5.4, Wall 3). The wall was 2 m wide in the road cut, built on top of bedrock, with an attached 1.4 m wide wall. Approximately 9.7 m separated these paired walls from a parallel 1.65 m wall. Surrounding these walls' eastern and western limits was stone, presumably bedrock (Boehmer and Fenner 1973, 490–491). The architectural drawing of these walls in Abb. 19 evokes immediate and apparent parallels to the road cut section that revealed Gund-i Topzawa’s structure. Four decades of erosion obscured the material at Mudjesir, but the Gund-i Topzawa excavation establishes that these walls were not likely part of some city wall but a structure.

To the southwest was the raised area, surrounded by hills and adjacent to the road, Boehmer termed the “Upper City.” While unable to detect a further extent of retaining wall (or city wall) that encircled the village, he recorded numerous wall fragments protruding from the surface, constructed with hewn stones, along with many sherds (Boehmer and Fenner 1973, 491). RAP’s survey of this portion of Mudjesir in 2016 located a recent large hole, possibly from construction activities, filled with modern trash (RAP28). The walls visible in the hole revealed 4-6 courses of a wall on the southern face, with the top course approximately 50 cm below the surface. The wall was constructed in the characteristic alternating perpendicular stone courses seen at Mudjesir and in Gund-i Topzawa Building 1B-A. The wall appeared to run into a perpendicular section in the western balk, though it could not be traced further. The wall’s corner may have been exposed in the east, or the hole cut a portion of the structure. Given the abundance of trash, we were unable to fully recover ceramics from the site, but we did record many fragments from what seemed to be a single large pithos, though it lacked any diagnostic features, as well as a single small rim sherd, possibly from a bowl (Plate 54.2). In addition, nearby was a somewhat recent stone structure (RAP31) that collapsed on the surface, likely from the last century (or more recent, if Boehmer’s absence of recording was due to its non-existence). An earlier survey of this area in 2014, further uphill to the west, also noted a few wall fragments protruding from the surface and a single rim sherd (Plate 52.2).

Along with the architectural features at Mudjesir, Boehmer recorded two column bases in the village, an arrowhead, stone disc, stone bowl, and an oblong worked stone with indention marks around its midsection, all from the area of the Lower City. Among the architectural features and movable artifacts were two column bases, one dated to the Urartian Period and one to the Hellenistic Period. The Urartian base was located below the surface of the village, with a diameter of .9 m, a height of .55 m, and a relatively simple rounded shape with an extended mid-section, made of limestone with a mortar hole at its top created by the villagers. The other was located just north of the village, near the outer retaining/city wall. It had a more elaborate design, with a bell-shaped base, incision, and rounded top, measuring .36 m tall and .64 diameter at its base (Boehmer and Fenner 1973, 491–492). Boehmer dated this base to the Achaemenid 4th century, given its distinctive style. While RAP may have recorded one of Boehmer’s column bases in the village and an additional two further downstream (RAP30), Dlshad Marf’s survey and overview of 17 column bases provide more extensive cataloging and connection to Boehmer’s objects (Marf 2014, 15–18). His Figure 1, B records the column bases of RAP30. The column bases in his article are mainly similar to Boehmer’s Urartian style, with two having two horizontal incisions that compare to a column base at the Urartian site of Altintepe. In addition, Boehmer noted the older, Ottoman-era fort in the center of the Mudjesir village, but did not describe any archaeological features. The building still stood at the time of RAP’s surveys at Mudjesir and was used by the village residents.

##### RAP - Mudjesir Sites

A prominent cultural feature with continuity between RAP and Boehmer surveys is the sizeable modern road towards Sidekan. While the road seems to have been widened somewhat since the 1970s, Boehmer’s mention of the road and a wall it cut emphasizes the importance of road cuts in locating archaeological material, a trait demonstrated again with the Topzawa Valley road and Gund-i Topzawa. The 2016 survey and 2015 pottery collection of the road cut, concurrent with the Mudjesir field excavations, recorded multiple sites along the road cut. The delineation of the sites was largely arbitrary or reliant on small architectural or topographical features, as the whole Mudjesir area should be thought of as one coherent unit. However, the easternmost road cut site (RAP32), at the southwards bend of the road, had architectural features that warranted a unique site description. Between the road and the eroded hillside was a ditch running parallel to the road. This section of the ditch contained many stones in a similar pattern to the Gund-i Topzawa road cut. Delineating any walls was impossible given the low exposure and inability to clean the section, though we established the position of at least one wall with a high degree of certainty.

RAP32’s diagnostic pottery establishes at least an Iron III date, with an outside chance of later occupation. Four of the diagnostic rims were from bowls that connect to the Gund-i Topzawa typology. One of the bowls (Plate 55.2) is included in the GT typology Bowl 12, straight-sided with everted rims and connects to Kroll type 13a, an 8th-century form. Another (Plate 55.3) was a carinated shallow bowl with a simple rim comparable to GT Bowl 7, primarily found in Building 1-W Phase B Room 1 and common in the 8th and 7th centuries. Another carinated shallow bowl (Plate 55.5) with a thicker body (Plate 55.3) relates to GT Bowl 11b, a type of carinated bowl found in Rooms 1 and 2 in Building 1-W Phase B.

Another bowl (Plate 55.4) compares to Bowl 13, related to Kroll’s type 22. While not a perfect match with Kroll 22, he describes that type as mainly Achaemenid through Parthian periods, though its style was common at Urartian era sites, including Hasanlu IIIA, Godin Tepe II, and even Mudjesir, sherd #4 in his Boehmer’s 1973 publication. The related material at RAP32 and the date of sites with comparable sherds suggest this sherd was not from the Achaemenid Period. Another sherd (Plate 55.7) compares to Kroll type 25, which he dates as Late Urartian through Achaemenid. Like type 22, comparanda were from Urartian era sites like Hasanlu IIIA and Bastam B, as well as Hasanlu IIIB. This pair of sherds may not necessarily establish an Achaemenid date for this site, but rather a Late Urartian dating, consistent with Iron III.

RAP32 was the sole Mudjesir area survey site with a non-ceramic artifact. The object was one of the most intriguing artifacts recovered from either survey or excavation. It was a collection of viscous, burnt material that appeared to be slag from metal production. Given the constraints of fieldwork, we could not examine it in sufficient detail to understand the metallurgical characteristics of the object or if it was slag from metal products rather than burnt material from an unintentional fire. However, the surrounding area and walls did not show any of the tell-tale signs of large-scale burning like that at Gund-i Topzawa, providing circumstantial evidence the slag was associated with metal production. If so, it raises the possibility of metal production in the central area of Muṣaṣir. Along with the slag was a 17 cm long flat worked stone, made of a sandstone-like stone. One end was slightly pointed, and its flat surface had a pair of small divots, ca. 2.4 cm in diameter. The purpose of the stone is unknown, but its general form does compare to a similar stone from Gund-i Topzawa Building 1-W Phase B, Room 3, with an equally uncertain purpose. These objects suggest, however, that RAP32 served some industrial or production function.

RAP33 was located a few meters further east along the road cut and referred to the collection of pottery that eroded from the escarpment, roughly an area 10 m wide and 15 m up the hillside. Most of the pottery was collected directly after a large rainfall in which some wall-like features between bedrock outcroppings were visible but not recorded or photographed. The relatively significant quantity of pottery, however, does assist in establishing the chronology of occupation in this area of Mudjesir. Twenty out of the thirty diagnostic sherds were included in the publication and analysis of the Mudjesir excavations by Danti and Ashby (Forthcoming). The full index of sherds and relationships to the Sidekan ceramic typology is in the Appendix. Overall, the assemblage resembles the fill of the Mudjesir excavation above the drain, dating to the Middle Iron Age/Iron III with continuity to the broader Urartian assemblage. Of the thirty diagnostics, twenty-two connect to the Gund-i Topzawa ceramic types, as noted in the Appendix.

RAP34 was further east along the road cut, roughly 10 m from the RAP 33 collection area, and yielded one diagnostic sherd. The sherd was an orange ware, and while it did not perfectly fall into a Gund-i Topzawa type, it has some resemblance to HM type 1, and its appearance is typical of Iron III. RAP35 was ca. 10 m east on the road cut and was also just a collection of pottery emanating from the eroding section. Of the five diagnostic sherds, two clearly connect to Gund-i Topzawa, one has parallels to that material while lacking an exact match, and one has no match from that site but is typical of Iron II/Iron III. The two bowls, (Plates 57.4, 57.3) fall into the Bowl 1a type from Gund-i Topzawa 1-W Phase B, deep carinated bowls with out-turned rims, which match to Kroll’s type 24, a 7th century and later form. Among the many sites with that type is Boehmer’s Mudjesir survey (nos. 5, 60, 63). Another of the sherds from RAP35 (Plate 57.3) has a rim that could compare to Bowl 4 or Jar 3a from Gund-i Topzawa, another datum of evidence for an 8th or 7th-century date for the assemblage. While divided into different sites during survey and collection, RAP32 – RAP35 are best conceptualized as one site with the individual RAP site numbers delineating collection units.

RAP36 was also on the Mudjesir road cut, but further east, past the road’s southward bend over the small creek, uphill on a small path leading up to the top of the adjacent hill. From the reconstruction of Boehmer’s map, it seems to be almost directly uphill from the parallel triplet of walls in the road cut Boehmer noted. Despite the amount of erosion, we recovered pottery from only a small area and could not locate any architectural features in the exposed areas of the hillside. Overall, the pottery assemblage corresponds to the rest of the Mudjesir survey pottery, excavation material, as well as ceramics from Building 1-W Phase B. RAP36 was the only survey site to have a cup rim, which unfortunately did not have any match to any Gund-i Topzawa material, likely due to the paucity of cups at that site. Three sherds (Plates 58.1, 58.4, 58.6) related to GT types HM 2a, Jar 4, and Bowl 2b, respectively. Notably, Jar 4’s only example from Gund-i Topzawa was from the space between Building 1-W Phase B and 2-W, believed to be contemporary with 1-W Phase B but with uncertain dating. Jar 4, however, does Kroll’s type 49, which he dates to the 8th through 7th centuries. Two other sherds (Plates 58.2, 58.3) do not have direct parallels in the GT assemblage or Kroll types but broadly share the ware and form characteristics common in Iron III, specifically the modeled rim of SUR.9.4. Despite the short distance from the rest of the road cut sites, the pottery at RAP36 suggests the occupation here was roughly contemporary with that area.

Two additional sites were not directly along the road cut, but earth-moving activity associated with the road constructed likely deposited the material at its present location from its original location near the road. RAP27 was a collection of ten sherds, only one diagnostic, mainly made from the orange wear common across Mudjesir. The one diagnostic sherd was an orange ware body sherd with a modeled and angular band. This detail was insufficient for exact dating but matched individual stylistic additions for Iron II/III pottery in the region. The sherds were on the hillside, ca. 30 m below the road, where the modern road curves around the small, raised a bit of topography that delimits the western edge of Mudjesir. In antiquity, this hill would have served as a natural barrier for anyone entering from the west. A few stones were visible in the section, but there was insufficient evidence to interpret these as architectural features. RAP29 had a similar small collection of pottery (8 sherds) with one diagnostic lacking sufficient detail for dating. The wares of these sherds match those of RAP29. The collection of this material was at the hillside base, alongside a small path running parallel to the Sidekan River. Like RAP27, several large stones extended from the hillside, but provided no evidence of architecture.

RAP recorded one additional site at Mudjesir, RAP26, some distance to the east – past the village, the “Upper City,” and the bend in the road. The orchard owner of the fields that span the area between the Sidekan-Mudjesir road and the steep hillside to the south led us to this location. Despite the report of archaeological material in this area, the semi-intensive survey of the hillsides recovered only a collection of very small sherds – with far more resemblance to pebbles than pottery. Most were revealed only after disturbing the soil around the orchard’s trees, and none were immediately visible on the surface when walking through the area. The surface, however, was heavily overgrown and covered with foliage at least 20-30 cm tall. None of these small fragments were diagnostic or preserved well enough to make any conclusions about their dating or other characteristics. Survey of this hillside can only indicate the likelihood of archaeological occupation, but we were unable to ascertain if it was contemporary to the rest of the observed material at Mudjesir. In addition, 2016’s survey of the hillsides north of the Sidekan River and Abdulwahab Suleiman’s independent survey of that area located no archaeological features or artifacts, even with the somewhat recent road cut providing a clear section to search for material. The thin topsoil above the bedrock likely either prevented occupation or wiped away any remains post-depositionally. We currently have no way of determining if this northern slope had a similar lack of topsoil in the first millennium BCE.

A notable point in concluding the survey of Mudjesir was the absence of distinct Achaemenid ceramics. Boehmer’s record of a stylistically unique Achaemenid column base (Abb. 22) was the only Achaemenid artifact, and its monumentality indicates some type of Achaemenid occupation, as column bases are traditionally non-movable objects. RAP’s excavations of Gund-i Topzawa and Ghabrestan-i Topzawa established Achaemenid burials in the region during that time, and the quality of burial goods suggests at least somewhat elevated status for these deceased people. Further intensive survey of Mudjesir can shed insights into the status of any potential Achaemenid occupation – whether it existed at all or later taphonomic processes wiped away the more recent phases.

The ceramics from the RAP survey and excavation of Mudjesir reinforce Boehmer’s conclusions that the ceramics bear far more resemblance to Urartian styles than Assyrian types. Further, the combination of the excavation of the Mudjesir field, Qalat Mudjesir’s recent survey and excavation, and the survey of the area around Mudjesir provided no evidence that would refute Boehmer’s overall postulation as Mudjesir as Muṣaṣir (Boehmer and Fenner 1973, 512–514). However, two of Boehmer’s points, the defensibility of Qalat Mudjesir and the direction of Sargon’s invasion, are possibly incorrect given data produced through this archaeological research and historical reconstructions after Boehmer’s publication, discussed in detail in Chapter 7.

##### RAP – Mudjesir Excavations

In 2015, Soran Director of Antiquities Abdulwahab Suleiman permitted RAP to conduct two test soundings in the fields of Mudjesir, followed by a short investigation of Qalat Mudjesir by Dr. Danti in 2019 (Danti and Ashby Forthcoming). The previous season, 2014, Jörg Fassbinder (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München) and his team conducted a geomagnetic survey of Mudjesir and Qalat Mudjesir as part of the larger RAP project (Fassbinder 2016). The excavations and geomagnetic survey, combined with the pedestrian survey results, provide a broad dataset of ceramics as well as insights into the nature of the buried architecture.

The geomagnetic survey at Mudjesir’s fields (Boehmer’s “Lower City”) covered a combined area of about 40 x 60 m. As part of the preparation of the area for geomagnetic survey, we removed many pieces of metal shrapnel, including large munitions. The quantity and type of metal support the local informants’ information about grading of the site for a military emplacement at the location during the Iran-Iraq War. The 2015 excavations dug through large quantities of metal shrapnel in the topsoil and the highest stratigraphic levels, and further survey on the site collected further metals, suggesting the magnetic signatures may have been artificially altered. Even access to the full 40m x 60 m area was largely constrained by a series of fences and, most disruptively, a beehive. These disturbances limited the magnetometer survey to two areas in the full grid. Mudjesir’s metal shrapnel undoubtedly affected the accuracy of the geomagnetic survey, but the results “showed several rectangular pits, filled with highly magnetic debris, and on the other hand faint traces of several rectangular constructions. The latter are interpreted as the ground plans of at least three buildings while the former may be cellars or storage pits carved into the bedrock” (Fassbinder 2016, 118). Given the amount of metal buried directly below the surface revealed in the excavation, the cellars or storage pits may likely be false signals from the metals’ magnetic signature. However, the road or linear feature may correspond to buried architecture. In addition, the geomagnetic team surveyed Qalat Mudjesir, discussed below.

With the substantial evidence of archaeological occupation and suggestive evidence for Ḫaldi’s temple at Mudjesir, the team laid down two small soundings (Operations 1 & 2). The 2015 season at Mudjesir lasted approximately a week (October 27 – November 2) and had to battle the heavy rains characteristic of early fall in Sidekan (Danti and Ashby Forthcoming, 14). Operation 1 began as a 2 m x 2 m sounding on a small prominence in the southeast corner of the field, near where Fassbinder located an area of high geomagnetic resistance. Unfortunately, the exact mapping point in 2014 was lost, so the team was unable to place the trench exactly on the geomagnetic anomaly. We placed Operation 2 northwest of Operation 1, near the edge of the field where column bases and other construction material were supposedly located, but the operation was abandoned after only two days, largely due to intemperate weather. Given the archaeological material’s concentration at the outer edge of the plowed field, seasons of plowing operations and field leveling likely pushed material to the side. Operation 2’s excavation only dug approximately 50 cm – 75 cm below the surface but uncovered a collection of stones laid out in a wall-like pattern. They apparently consisted of five stones in a line, running diagonally through the trench from southeast to northwest. To the east of the wall was a large amount of charcoal and ash, along with a number of pithoi fragments. This area of the trench was a small piece of green glazed pottery and a nicely preserved copper-alloy bracelet, with two flattened ends forming the opening. While the bracelet has superficial similarities to the far better preserved one at Ghaberstan-i Topzawa, the corrosion makes a confident identification difficult. Despite the low depth of excavation, the pottery and artifact preservation show no clear signs of disturbance by plowing or similar surface operations.

Operation 1 revealed a large stone drain at the bottom of the 2015 excavation (Danti and Ashby Forthcoming, 15–16, Figure 7a, 7b). The first 2 m of the excavation consisted of a single layer of stone chips with large fragments of animal bones, numerous sherds, and fragments of baked brick. Apart from one orange ware sherd with matte-black parallel painted lines, the entirety of the ceramic assemblage in the fill consisted of Iron III pottery comparable to the Gund-i Topzawa assemblage (Danti and Ashby Forthcoming, 19). At the bottom of this layer was a clay surface, covering a horizontal drain below. Removal of flat stones covering the drain uncovered a channel approximately 70 cm wide and 75 cm deep, measured from the removed stone above. The drain’s side walls were two stones wide. The eastern wall consisted of four-courses of river cobbles and three courses of river stones with smaller stones on the west. The drain’s cover was paved with rectangular stones and rounded cobbles. The stone structure slopes downwards from south to north towards the river. Of the exposed 1.7 m, the elevation of the drain’s floor dropped 44 cm, a slope of 26% (Danti and Ashby Forthcoming, 16). Looking south, through the open area of the drain, under unexcavated areas above, the team saw the drain running below what appears to be a large stone wall running perpendicularly.

In the fill of the drain were striated layers of organic material with small sherds, bones, and a single piece of charcoal. The sample returned an uncalibrated 14C Age (1) of 2719 24 14C years BP equating to a calibrated date range of 895 – 833 BCE(68%), the Iron II Period (Brock Ramsey 2017; Reimer and et al. 2013). Continuing usage of the drain, with water and other refuse flowing through, would wipe away the charcoal from its location, indicating the charcoal dates near the end of the building’s use. Returning to the existence of the large level of stone chippings and the hypothesis that the chippings are some sort of leveling operation, a narrative emerges. The drain and the associated building seen in the excavation were leveled between 895-833 BCE, and a new structure, likely containing the column bases that litter the modern surface, was built on top of the old structure.

The monumental nature of the drain, combined with the large nearby wall, lends credence to the idea of a large monumental structure, like the Ḫaldi temple. Fassbinder’s ancient road loosely corresponds with the direction of the drain, which could indicate at least 10-15 m of the remaining drain. Unfortunately, the misalignment of the 2014 and 2015 mapping cannot confirm this accurately, and the gap in the magnetometer grid perfectly misses the suspected area of the monumental building. The 2 m of stone chips are unique for the homogeneity and depth, as well as the distinct combination of stone with archaeological material. One theory is these chips were a deliberate fill to create a platform above. In the Muṣaṣir relief, the temple appears to rest on a large base or platform that is conceivably made of stone chippings. Other roughly contemporary sites used construction techniques that may resemble this type of platform. At Gordion, the Terrace Building Complex, an Early Phrygian structure destroyed ca. 800 B.C.E., rests upon a thick layer of stone fill. The rubble consists of 4 m of large stones, seemingly quarried for that purpose, covering a much earlier Early Bronze Age structure, dating as far back as the third millennium B.C.E. The purpose of the rubble was apparently to create a large, flat platform, extending the limits of the main citadel mound (Rose, Brian C. 2017, 155–157). Another site’s large terrace may provide further evidence, although its fill was not filled with as much stone as Gordion. At Persepolis, a façade of masonry blocks creates the foundation for a large terrace that holds many of the important buildings at the Achaemenid capital. In order to level the surface, the area inside the surrounding retaining wall was leveled. At some points, this meant scarping the exposed bedrock and adding those stone chippings to the lower sections (Schmidt 1953, 61). Further, at an Urartian site, Ayanis, a series of pillars surrounding a building were constructed on a layer of stones, not unlike that at Mudjesir. The builders placed a collection of stones around the exposed rocks, then “a layer of thick pebbles between the two,” creating a strong, flat bed for the pillar’s construction (Bilge 2012, 2–3).

In October 2019, Dr. Michael Danti returned to Mudjesir and was given permission by Abdulwahab Soleiman and the Soran Directorate of Antiquities to excavate a portion of Qalat Mudjesir’s central building and Inner and Outer Baileys. Over two weeks, he traced the outline of a buttressed corner of the Central Building, located its doorway, and cleared a small portion of the structure’s interior. A sounding was also completed in the Outer Bailey in an area that geomagnetic mapping indicated probably contained pits and/or midden deposits. The doorway in the eastern wall of the Central Building, off-center near the northern wall, was constructed with six large baked bricks, a style far more common in Assyrian monumental structures than those excavated at Urartian sites in Turkey, Iran, and Armenia. The stone walls had large, flat blocks on both faces, with stone rubble filling in the space between the exterior faces. Overall, the outer stone walls matched Fenner’s plan and the geomagnetic mapping of the building, with the wall gap in Fenner’s plan corresponding to the doorway. Deposits inside the building indicated the structure had been destroyed in an extremely hot conflagration event, with ash and charcoal layers and an extremely hardened and discolored clay and natural bedrock surface— the original floor of the Central Building. Lumps of fire-hardened and discolored clay in the destruction deposit bore reed and grass impressions, indicating this material likely originated in the structure's roof surface. Radiocarbon dating of carbon from the building’s interior —probably from roof beams used in the original construction—returned dates from the 9th century BCE. The small amount of diagnostic pottery from the structure’s interior and from the Outer Bailey matches the Iron II/III pottery from the excavations and survey of Mudjesir. In addition, a later tanoor cut into the structure’s wall, with Islamic Geruz Ware, indicating at least a minimal later occupation at the site (Danti, personal communication).

Additional Boehmer Site Resurveys

Boehmer’s quick but thorough survey in Sidekan in the 1970s was instrumental in all of RAP’s excavation and survey work. It established the existence of significant archaeological remains from the Iron Age and the variety of features in Sidekan. Our return to Sidekan, four decades later, required returning and resurveying Boehmer’s sites, necessary for multiple reasons. One, determining the continuity or preservation of sites is of interest to survey analyses and cultural preservation questions. Second, the drastic improvement in mapping technology allowed us to provide specific locations and coordinates of the sites Boehmer placed on his hand-drawn maps. Third, seeing the context of sites Boehmer recorded, their position on the landscape, and surface features, helped train our eyes to recognize features that may correlate to archaeological remains.

##### Schkenne (RAP 19)

For the purposes of locating Muṣaṣir, Schkenne was one of the most interesting sites Boehmer surveyed during his brief trip. Before Boehmer’s fieldwork in 1973, Lehmann-Haupt passed through the area, noting not just the Topzawa Stele but the so-called mound of Schkenne nearby (Lehmann-Haupt 1926). Given its proximity to the stele and ideal location on a promontory he believed was an archaeological mound, he proposed Schkenne as the location of Muṣaṣir. Prior to Boehmer’s October 1973 survey, he made a short visit to the site in June 1971 (Boehmer and Fenner 1973). He recorded a small square building on the hilltop with a possibly newer wall further down the hill’s slope. The outer stones were made of large blocks with smaller stones in the central structure. He postulated the lower wall might have served as a terrace in antiquity. However, the central building was much newer and prevented determination if an older building was below. The building’s shape and related ceramics were comparable to Kaune-Sidekan, believed to be Nestorian from the preceding centuries. However, among the sherds were Iron Age Urartian types, including a bowl with handles and a holemouth jar common at Urartian sites in Iran, dating the lower structure to the 8th or 7th centuries BCE (Boehmer and Fenner 1973, 481–486). Despite the ceramics, Boehmer did not believe the location was either Muṣaṣir’s palace or temple.

On June 17, 2014, I surveyed the site with RAP team members from LMU Munich and Dlshad Abdulmuttleb Mustafa from the Soran Directorate of Antiquities. Our time at the site was minimal, as the local landowner quickly came to request our quick departure from the site and was not amenable to archaeological work there because of his fields covering the site. In our brief time, we did observe the outer walls Boehmer described on the lower slope of the hillside. The central building had a large hole in its center. However, the walls were not visible in that hole, but soil mounding in a generally square shape indicated their location. During the conversation with the landowner, he indicated that the building had belonged to an older woman and collapsed after her death. As the structure appeared to be the same that Boehmer noted, the story may describe the building’s use before Boehmer’s fieldwork. Despite the large hole in the mound’s center, our team could not locate any ceramics in the hole or the surrounding slopes. Even without artifacts, the physical surrounding reinforces the ideal positioning of the site. From the top, one can see most of the area around the modern town of Sidekan, although not to Mudjesir or Qalat Mudjesir, and its location serves to manage access from the Topzawa and Bora Valleys, with steep slopes providing additional impediments against attacks. While neither Boehmer nor our team determined this as Muṣaṣir’s temple or palace, any future work should attempt to lay down a small test trench to gather information about the buried architecture, chronology, and ceramic types.

##### Tell Bayin do Rubar/Gird-i Newan do Rubar (RAP 24)

Nearby Schkenne, at the peninsula between the Topzawa and Bora Rivers, was the site Boehmer recorded as Tell Bayin do Rubar. He noted stone walls protruding from the soil along the outer edges of the small mound but no other architectural features. The only ceramics recovered were a few body sherds with a vague resemblance to those from Kaune Sidekan. He was unable to date the site but noted its advantageous position, with viewsheds of the plain of Sidekan, views eastwards towards Topzawa, and steep sides down to the river below (Boehmer and Fenner 1973, 487–488).

Our team resurveyed the site on June 19, 2014, and observed the same walls Boehmer recorded, with some additional context. Like Schkenne, the same landowner quickly forced us to cease our site survey, although we had sufficient time to walk all of the small site. We noted walls sticking out from the north and south of the main mound, on the portions facing the steep drop to the river. One section of the narrow walkway-like earthen ramp to the mound had flat stones on the surface, resembling a deliberate pavement, but we could not investigate further. We recovered no ceramics. Boehmer noted that Tell Bayin do Rubar translated as “the mound between two rivers,” but his recording may have relied too heavily on his Arab guide’s interpretation. For one, tell is the Arabic term for a mound, rather than the Kurdish word gird. In addition, the landowner of the property described the site as Newan do Rubar, rather than Bayin do Rubar, although site names reinforce the importance of its location between the two rivers.

While Boehmer noted the strategic location of the site, he did not fully emphasize its defensive suitability. Reaching the mound itself, near the westernmost extent of the peninsula between the rivers, requires walking along a narrow ridge, almost 100 m long. The sides of this ridge are steep and lead towards the rivers on either side. Following the ridge to its westernmost extent was impossible, as it narrows significantly before the rivers join, making the mound extremely well protected. Walking towards the mound, one passes a large boulder on the right. The boulder had an acutely flat horizontal face that did not appear natural. There was, however, no marking or inscription. The width between this boulder and the other side of the path measured less than 10 m, raising the possibility that a matching boulder may have originally stood in its place as either a constructed or natural gateway. If Mudjesir and Sidekan were the core of Muṣaṣir, this site and Schkenne, a short walk up the hill to the east, would surely have been occupied.

##### Other Boehmer sites, not resurveyed

Three of Boehmer’s additional sites were not resurveyed during the RAP survey project, but our work in the area can provide additional insights and context. 750 m west of Sidekan on the road to Mudjesir was the small tell, with remnants of a small house from a recently deceased woman. The site was called Tell Schasiman after that woman’s name. Previous to her residency there, the site was apparently called Tell Gefr (Michael Rainer Boehmer 1973, 488). Our survey in the area did not locate the mound or note any topographic feature like that Boehmer described, despite frequently traveling to the same area.

Boehmer also surveyed the abandoned village of Kaune Sidekan, located on the southern bank of the Sidekan River, 2 km west of Mudjesir. The village was on a flat plateau that he believed was not natural. Multiple buildings were visible, with portions of their corners and walls exposed under a mass of debris. He collected a variety of pottery from the site, including the tell-tale green glaze of Islamic Gerrus ware. Nearby the village was a boulder with an incised ram, likely made by the Nestorian residents of this village Lehmann-Haupt described as he passed through the area, leading to Boehmer’s conclusion that the pottery assemblage was a Nestorian type (Boehmer and Fenner 1973, 517–521). While Nestorian is a religious denomination, not a periodization, Boehmer associated the Nestorian occupation with the residents of the area during Lehmann-Haupt’s survey more than a half-century earlier. In 2016 we drove to Kaune Sidekan and observed the same collapsed buildings Boehmer noted but did not have time to leave the vehicle to collect material or view the incised ram.

Boehmer also described a burial dolmen in the village of Huwela, a few kilometers south of Mudjesir. The single tomb had a stone covering about 1.1 m wide, 2.0 m long, and .37 m thick. During Boehmer’s fieldwork, only about 1 m of the structure was above the ground, with a grouping of stones, largely obscured, creating an entrance. He noted that this type of stone dolmen structure is not known from Mesopotamia or the surrounding area but rather connects to the culture in northwest Iran (Boehmer and Fenner 1973, 515–516). He recovered two sherds contemporary to Mudjesir, dating to the 7th or 8th century BCE. We did not attempt to locate this site, but the excavation of Ghaberstan-i Topzawa demonstrated that this type of stone construction, while abnormal for Mesopotamia, was less unique in the Sidekan area.

Sidekan & The Topzawa Valley

As the eponymous seat of the Sidekan region, one expects the modern town of Sidekan to connect to significant archaeological remains. However, from the limited survey and discussion with town residents, the immediate area showed minimal cultural material from antiquity. Analysis of CORONA imagery from 1968 and 1969 of Sidekan’s central plain shows the wide valley was devoid of any large or visible structures. Sidekan, at that time, was a small village to the east of the modern town, covering less than 3 hectares, directly adjacent to Gird-i Newan do Rubar. Less than a decade after the capture of CORONA imagery, Boehmer's survey of the area did not note any archaeological sites in this area. He described, however, several new buildings, including a school next to a fortress (Boehmer and Fenner 1973, 517). Along the main road through modern Sidekan is a sizeable fortress-like building built on top of a tall mound or hill. Kurdish security forces occupied it, so we could not examine the structure, but Boehmer’s fortress may refer to the same building. CORONA imagery from 1969 shows a small mound at the location in question, without a structure on its peak. Around that area, Boehmer recovered handmade decorated pottery that appeared contemporary to sherds from Kaune Sidekan, postulated as a late site, possibly occupied by Nestorians during Lehmann-Haupt’s travel through the region (Boehmer and Fenner 1973, 517). The fortresses’ existence prevents any archaeological reconnaissance or targeted excavations from determining if the feature was natural or archaeological.

As noted in the discussion of Sidekan Bank’s excavation, that site contained minimal archaeological material, mainly consisting of large burning concentrations and few features, suggesting temporary or ephemeral occupation, unlike Mudjesir or Gund-i Topzawa. The intensive pedestrian transects of the surrounding hillsides between the river and the modern buildings along the road recovered almost no ceramics, and none had identifiable characteristics. In addition, recent construction nearby the original Sidekan village neatly sectioned a small, round mound. Despite its exterior resemblance as an archaeological mound, the section revealed its natural identity, with only one large pithos sunk into the surface and largely destroyed by the construction. That behavior is consistent with nomadic or temporary occupation, reinforcing this area's probable type of use. Unfortunately, RAP did not have an opportunity to survey the hillsides around the Sidekan plain where, if paralleling Mudjesir and Gund-i Topzawa, we would expect permanent constructions.

One of the most crucial concentrations of sites in the Sidekan survey was along the Topzawa Valley, revealed by the road construction previously discussed in-depth with the Gund-i Topzawa and Ghaberstan-i Topzawa excavation sections. The road widening began just east of the older side of Sidekan, directly adjacent to Newan do Rubar. The construction exposed a length of approximately 8.5 km along the valley. Of that length, 3.8 km were intensively surveyed, examining the road cut’s section for architectural features, burning, or concentrations of artifacts. The segment stretched from Gund-i Topzawa (RAP17) eastwards to RAP22 (discussed below), along with the section directly adjacent to Ghaberstan-i Topzawa (RAP16). The unsurveyed sections are between Gund-i Topzawa and Ghaberstan-i Topzawa, and the section spans the westernmost extent of the road east to RAP22. Frequent drives past these areas, however, noted the presence of possible archaeological material in the exposed sections.