The most notable historical occupation in the Sidekan area, and the focus of this dissertation, is the Iron Age kingdom of Muṣaṣir. Despite the millennia of human settlement in this region, the historical record is comparatively bare. Apart from a handful of rare inscriptions, the history of Soran comes from reports and tales of outside travelers, conquerors, and spies. While Sidekan is the primary focus of this analysis, Soran and Sidekan are inextricably linked throughout history as two small refuges in the largely inhospitable northern Zagros Mountains. Thus, the history of Soran is vital for understanding the annals of its smaller neighbor, Sidekan. Further, the dearth of historical texts from Sidekan and Soran themselves forces us to examine the history of Sidekan largely through the lens of outsiders, with only small archaeological and ecological clues revealing the identity of its occupants. In this limited historical dataset, the Iron Age kingdom of Muṣaṣir stands apart as one of the few periods of note.

Across history, Sidekan appears only periodically in direct and indirect references. While literature and historical documentation only began referencing the area as Sidekan in the last few centuries, a combination of geographic and historical triangulation reveals the region’s identity throughout time. The dual geographic features of the Rowanduz Gorge and the Kelishin Pass provide immutable anchor points when using historical accounts to reconstruct the area. While the names of these features evolve over millennia, their unique characteristics provide a connection to the modern names. By utilizing geographic clues, the existence of an inscription at the Kelishin Pass, and data from an archaeological survey of Sidekan by Rainer Michael Boehmer in the 1970s, scholars now believe that the core of Muṣaṣir was in the area of the modern Sidekan subdistrict (Boehmer and Fenner 1973). Urartu, the mountainous Iron Age empire to the north, with its capital of Tušpa at Lake Van, revered Muṣaṣir. According to contemporary texts, Muṣaṣir was home to the temple of Ḫaldi, the head deity of the Urartian pantheon, bestowing the kingdom prominence to the Urartian rulers (Çifçi 2017, 257). Apart from references to Muṣaṣir, historical documentation of the area is minimal.

Preceding the Iron Age and Muṣaṣir, textual accounts from nearby regions suggest a possible identification of the area as Kakmum, although that identity is far from certain. The relationship between the Bronze Age occupation and the Iron Age is important for establishing the origins of Muṣaṣir as well as the Urartian Empire and its rulers. After the Iron Age and the fall of Urartu, Sidekan’s identity is far more obscure. Extrapolating from present names and geographical relationships indicates that a possible name of the area during the Classical Periods was Aniseni. This name appears periodically throughout history in reference to tribes or small sections of the area. After the Muslim Conquest, the area disappears from the historical record minus a few individual references to geographic features by travelers and geographers, noting the Kelishin Pass. Eventually, during the Ottoman rule, the Sorani Emirate arose, providing a concrete anchor to locate geographical polities around the core of the state, the Diana Plain. The name Sidekan does not occur as a noteworthy political entity during this time, but traveler’s accounts confirm continued occupation, albeit extremely limited and hostile to outsiders.

The overall history of the Sidekan region appears to begin with some occupation in the Late Bronze Age, before reaching its height and importance in the Iron Age, with neighboring empires and kings fighting to exert influence over the area. After Muṣaṣir’s temple and Ḫaldi’s fade into irrelevance, Sidekan shrinks and largely disappears from the historical record until after the Muslim conquest. History alone can not serve as evidence for the region’s irrelevance for a millennium, but it does suggest that Muṣaṣir’s role as a significant player in local geopolitics was short-lived. By combing the historical record and correlating periods of archaeological occupation, it becomes clear that Muṣaṣir’s thriving kingdom was abnormal for the region. Overviewing the history provides a window into the settlement patterns of the Sidekan area and places the region into context with its larger neighbors.

Early Bronze Age

Understanding and identifying the possible polities located in the Soran district during the Bronze Age requires an overview of the major states and groups in the Trans-Tigridian corridor, utilizing their relative locations and outside references to identify this mountainous region. The possible identification of this area is Kakmum, determined by locating various toponyms on the map of the Trans-Tigridian valleys and Zagros Mountain piedmont. Although textual sources provide limited information about the inhabitants and settlement itself, the descriptions help determine the origins of the later Iron Age state and establish the type of occupation in the area. Kakmum itself rarely appears in the textual records of the Mesopotamian plains and alluvium, but inscriptions from its better-known neighbor, Simurrum, note its importance in the machinations of the Trans-Tigridian potentates. Most of the key information about the mountain kingdoms comes from records of the larger Mesopotamian states throughout the Bronze Age, most notably the kings of the Ur III state.

Simurrum

A primary adversary and major source of textual information about Kakmum was the kingdom of Simurrum. Locating Simurrum with precision is vital for the relative positioning of Kakmum. Simurrum appears in various textual sources from the 24th through 18th centuries BCE (Altaweel et al. 2012, 9). Early Dynastic kings boast of capturing the polity and describe its character as a place “between the basket and the boat” (Alster 1997, 84, 104). Sargon of Akkad and his successor Naram-Sin both campaigned against the kingdom, dedicating year names to their attacks on Simurrum (Frayne 1993, 96; 1997, 246). Later, a Gutian named Erridu-Pizir records a king of Simurrum named KA-Nišba instigating hostilities among his people and neighboring Lullubum against the ruling Gutians (Frayne 1993, 224). After the fall of Guti, king Šulgi of the resurgent Ur III dynasty engaged in five separate campaigns against Simurrum in year names 25, 26, 32, 44, and 45 (Ahmed 2012, 237). Hallo (1978, 72) postulates that Simurrum’s vital location controlling routes between the Iranian plateau and Mesopotamia drove Šulgi’s apparent obsession with its conquest. The intensity of conflict led to him naming three of the years the “Hurrian wars” against Simurrum and nearby Karhar (Hallo 1978, 82). After the short period of Ur III rule over the area, a strong independent king of Simurrum rose to power, Iddin(n)-Sin, credited for controlling vast swaths of the Trans-Tigridian corridor and erecting monuments in his honor (Edzard 1957, 63; Walker 1985, 186-90; Whiting 1987, 22; Ahmed 2012, 220-275).

With attestations spanning the Early Dynastic Period to the Early Bronze Age, Simurrum serves as an anchor point for topographical names at the time. Although there is some debate over the exact location of the kingdom, most scholars agree on a general location east of the Tigris, in the valleys and semi-mountainous areas of the Trans-Tigridian corridor (Billerbeck 1898, 4; Meissner 1919; Forrer 1920; Gelb 1944, 57; Edzard 1957; Frayne 1997; Altaweel et al. 2012). The exact locations, however, have some variation. In the late 19th century, Billerbeck identified Simurrum and Zaban as the same localities, placing them on the Lower Zab River (Billerbeck 1898). Meissner then suggested a location near Kirkuk, mainly utilizing a Šulgi date-formula in which Simurrum and Lullubum are seemingly related and texts that conflate Simurrum with Zaban (Meissner 1919). Although multiple subsequent publications continued the identification with Zaban, Forrer and Weidner disagreed and determined that the two topographical names were distinct (Forrer 1920; Weidner 1945). The two names may indeed refer to the same entity, but Simurrum is the earlier name while Zaban arises in the Old Babylonian period, possibly under Sillī-Sîn and Ilūnā of Ešnunna, indicated by an archive of texts from Mê-Turran (Frayne 1997).

More recent publications argue for different locations closer to the Mesopotamian plains or further into the Zagros Mountains. Frayne originally proposed a locale much farther south, specifically on the Sirwan River, near Kifri, at the site of Qalat Shirwana, using the relative positions of Simurrum and its neighbors as the predominant factor (Frayne 1997). As part of his argument, he noted the similarities between the modern Sirwan and Simurrum names and the substantial defensive location of the town (Frayne 1997, 267–68). However, in a later article, he changed his proposed location to northeast of the Darband-i Khan, specifically “the wide river basin west to the modern Av-i Tangero,” (Frayne 2011, 511). Radner locates Simurrum in the Shahrizor, farther to the northwest, based on its fertility and natural defensive advantages, as well as the locations of rock reliefs and other topographic names (Altaweel et al. 2012, 9–11). The location of Mount Nišba, its identity known from later Assyrian sources as the Hewrman range, is of some importance for the kings of Simurrum and aides Radner’s identification. The findspot of the recently published Halidany Inscription at the archaeological site of Rabana, on the slopes of the Pira Magrun Mountain, led Ahmed (2012, 293-95) to suggest the site as the temple to Nišba, on the mountain of the same name. Using that evidence, in part, he arrived at the same conclusion for the kingdom’s location in the Shahrizor Plain, north of the Darband-i Khan Pass (Ahmed 2012).

Turukku

Simmurum’s positioning and relationship with its neighbors assist in understanding the location and identity of another Bronze Age polity, Turukku. Inscriptions of Simurrum, from the time of Iddi(n)-Sin, and the Old Babylonian era archive at Tell Shemshara describe a large, confederated state of possible Hurrian ethnicity located in the mountains above Simurrum. Turukku is simultaneously the geographical name of a land and the designation for a group of foreigners. While deriving the toponymic positioning of Turukku compared to Simurrum and Kakmum advances the understanding of the political situation in northeastern Iraq during the Iron Age, their ethnic identity and organizational structure reveal characteristics directly relevant in the study of Iron Age Muṣaṣir and Urartu.

Turukku appears as an adversary and ally at different points in the letters from ancient Šušara (Tell Shemshara) and Iddi(n)-Sin’s Jersusalem Inscription. The name occurs as a political entity and a description of a group of people. Letters between the major powers from Tell Shemshara report that Pišenden, a Turukkian king of the kingdom of Itabalḫum, attempts to enlist the kingdoms of Elam, Namri, and Nikum to join his struggle against Kakmum (Eidem and Laessøe 2001, 143–44). Another example, from Iddi(n)-Sin’s Jerusalem Inscription, uses the toponym “Tiriukkinašwe,” a word constructed from the ethnic term for the Turukku, Tirukku, and the Hurrian plural and genitive suffixes (Speiser 1941, 102, 108–9; Shaffer, Wasserman, and Seidl 2003, 26). In the cuneiform texts, this distinction between geography and ethnicity is often solved with determinatives for either a place or a group of people. Philologically, the determinative “LÚ.MEŠ,” indicating a collection of people, most often precedes the name Turukku (Ahmed 2012, 350). While the determinative logogram indicates the Turukku as a group of people, whether they were a separate and distinct ethnicity is a question, relying heavily on linguistic clues.

Durand (1998, 81) believes the ruling class of Turukku had an “undeniable” ethnic component, with a Semitic Amorite ruling class reigning over a Hurrian population. Much of Durand’s argument relies on equating Turukku onomastics with comparable Akkadian words and their associated meanings, establishing a through-line between the Mesopotamian language and Turukkean terms. He equates Turukkean names with Akkadian translations, such as Turukkean Itabalḫum with Akkadian Ida-palḫum, translated as “flank of the terrible,” Zazum as Sasaum, the Akkadian word for “moth,” and Lidaya as Semitic Lidum, “offspring” (Durand 1998, 81). These interpretations are plausible except for a seal of Pišenden in which Itabalḫum is written without the “ḫi” suffix, the Hurrian adjectival suffix, indicating the Akkadian connection of the word was not reflected by the Turukku people (Speiser 1941, 114–15; Eidem and Moeller 1990).

The Amorite invasion into Mesopotamia and its periphery, which Durand (1998, 81) posits led to this Semitic group ruling over a Hurrian population called Turukku. Archaeological evidence may lend credence to this expansion if one associates pottery typologies with ethnicity, the infamous issue of pots and people. Khabur Ware, a ceramic type emblematic of the first half of the second millennium, spreads across Mesopotamia and into some surrounding regions. One of the most distant locations with significant Khabur Ware pottery is Dinkha Tepe in the Ushnu-Solduz Valley, located just west of Lake Urmia (Oguchi 1997, 216). This area is in the general location of the Turukku and could indicate the spread of a Semitic ruling class onto the Iranian plateau, although archaeologists should be highly cautious assigning ethnic and linguistic characteristics to typological distinctions. Assuming some connection between the Khabur Ware ceramic assemblage, the presence of the pottery at Gird-i Dasht, on the Diana Plain (Chapter 3), provides circumstantial evidence for a connection between the site and this migration of people. However, the linguistic basis for an Amorite ruling class is minimal.

The rulers of Turukku were seemingly sufficiently powerful to leave a mark on the name of the ethnic group itself. Pišenden’s seals describe his father as “Turukti, king of the land of Itabalḫum” (Eidem and Moeller 1990, 636). This seal’s inscription and the similarities between names would seemingly indicate that Turukti was the progenitor of Turukku and its people, but one of Turukti’s seals casts doubt on that interpretation. The seal describes Turukti as the son of Uštap-šarri, also a king of Itabalḫum (Eidem and Laessøe 2001, 26, 160). Further, a text of Yaḫdun-Lim, dating 15 years before the start of the Tell Shemshara Archives, cites a person named Tazigi as “king of the Turukku,” eliminating the possibility of Turukti’s founding of the dynasty (Eidem and Laessøe 2001, 26). In addition, the Jerusalem Inscription’s toponymic amalgam of ethnicity and geography, Tiriukkinašwe, reinforces a character for the group extending beyond the royal titulary. Turukti’s name may derive from the geographic and ethnic term rather than the inverse. Evidence for Turukku rulers continues through multiple generations, until at least Zaziya, a contemporary of Zimri-Lim at Mari (Beyer and Charpin 1990, 625).

Regardless of the ruling class’s identity, the bulk of the Turukku population was apparently of Hurrian origin. Historically, the Hurrian language originated in the northwestern Zagros Mountains and spread to neighboring areas (Gelb 1944; Eidem and Laessøe 2001, 20; Zadok 2013, 5). Located near that core, the Hurrian influence on the Turukku is unsurprising. Eidem and Laessøe’s characterization of Turukku as “a group of kingdoms in the valleys of the northwestern Zagros, predominantly of Hurrian affiliation,” corresponds well with that interpretation (2001, 27). Despite the depiction of Turukku as comprised of dispersed groups, separated by geographic barriers, they do not appear to be primarily nomadic, contrasting some of the Mesopotamians’ stereotypes of these types of mountain populations. Although the Mesopotamian authors’ depiction of Turukku is of “very mobile guerilla groups waging mobile warfare,” the Tell Shemshara archives depict a sedentary population (Eidem and Laessøe 2001, 25). Rather than nomadic populations moving around the Iranian plateau, the populace prefers the comfort of warm and permanent domiciles. In a letter from the Turukkeans found at Mari, the Turkku speak of their affinity to their homes and resentment in leaving them to travel into the mountains (Charpin and Durand 1987, 132–34).

Sedentary populations led to agglomerations of people into states and kingdoms, not dissimilar from the large polities known on the Mesopotamian plains. Indeed, in Eidem and Laessøe’s analysis of Turukku through the lens of the correspondence at Tell Shemshara, the Turukkeans show evidence of “a fairly complex political organization in these polities, with systems of noble lineages sharing territorial power” (Eidem and Laessøe 2001, 25). While called Turukkeans, with an implied ethnic component through the use of logograms, the letters mentioning the Turukku often describe the specific kingdoms and capital cities. For example, Itabalḫum was the kingdom ruled by Pišenden, with its capital at Kunšum, but other kings and kingdoms interact with each other (Eidem and Laessøe 2001, 26, 134). These kings allied with each other, creating a federation called Turukku.

The political organization of the Turukku is only visible through the letters and inscriptions of external polities but reveals a multi-tiered system of organization. Apart from the main king, multiple officials conducted business and led armies of the Turukku federation, like Pišenden’s deputy Talpuš-šarri (Eidem and Laessøe 2001, 130). The language Pišenden used when addressing Talpuš-šarri and other subordinate Turukkean officials was far more respectful than the commanding terms kings like Šamši-Adad use to their underlings (Eidem and Laessøe 2001, 160). The Mesopotamian texts depict the Turukku as a collection of kings, headed by one paramount figure, with each kingdom based in a city in the mountains of Iran. While the Mesopotamian authors present a fully confederated political system, the available texts do not reveal the mechanisms behind the initial formation and extent of royal control. However, the inscriptions on elite Turukkean seals show a system of patrilineal succession, with a chain of at least three kings represented from Pišenden, Turukti, and Uštap-šarri. Whether the Turukkean kings extended their dynastic rule through consensus building or coercive violence awaits further study of Turukku texts or synchronizations of contemporary archaeological material. Intriguingly, the general structure of patrilineal succession over a confederated group of small Hurrian kingdoms mirrors the proposed formation of the Urartian state centuries later (Burney 2002; Zimansky 1985, 48-50).

Reconstructing the possible locations for Turukku and its constituent minor kingdoms plays a major role in understanding the historical geography of northwest Iraq and northeastern Iran in the Bronze and Iron Ages. As a large portion of the texts concerning Turukku originate at Tell Shemshara, the toponyms location is a crucial piece in the puzzle of Turukku. The Tell Shemshara letters specify Turukku’s higher elevation compared to Šušara. Further, accounts concerning travel to Turukku use the Akkadian verb “elûm,” which literally means to “go up,” but is also used in the context of rising in elevation into the mountains. Travel from Turukku to Tell Shemshara uses the term “warādum,” going down (Eidem and Laessøe 2001, 28). The path onto the Iranian plateau from Tell Shemshara passes by Qalat Dizeh, rising into the mountains to Mahabad (Levine 1974, 102). Turukku’s near-complete absence from textual archives on the Mesopotamian plain supports a location on the Iranian plateau, some distance from Mesopotamia.

Turukku’s specific location on the Iranian plateau requires postulation and contextual clues. Given the federation of settled cities, one expects relatively large valleys and agricultural zones supporting the various constituent kingdoms. Eidem and Laessøe propose the Lake Urmia basin as the core of Turukku, primarily based on its size and population (Eidem and Laessøe 2001, 28–29). The geography of the basin corresponds well with the expected political makeup with Turukku, with many semi-isolated areas of sedentary occupation around one contiguous area. Further, Šušara’s subservient relationship with Turukku connects to the translation of Utûm as “gate-keeper,” as that site guarded the main passage into the mountains nearby Qalat Dizeh. Pišenden’s letter requesting assistance from Elam and Namri against Kakmum also establishes Turukku’s location in Iran adjacent to another Trans-Tigridian entity, Kakmum.

Kakmum

Kakmum’s appearance in the texts of the Bronze Age, contemporaneously to Turukku, reveals a semi-nomadic group of people located somewhere in the mountainous area north of the Rania Plain. The toponym’s possible location around modern Soran helps illustrate the history of Sidekan before the rise of Muṣaṣir. However, locating Kakmum first requires parsing whether the various texts discuss the earlier entity of Kakmium or the Trans-Tigridian Kakmum. Kakmium is first mentioned in texts from Ebla when describing a person named Ennaya from the city of Šubugu in the region of Kakmium (Pettinato 1981, 216). Scholars have different interpretations about the location of this polity. Unsurprisingly, scholars focusing on the Ebla material tend to locate Kakmium in Northern Syria, near Ebla (Archi, Piacentini, and Pomponio 1993, 326; Bonechi 1993, 144–45). Röllig mentioned only the Trans-Tigridian Kakmum, although his article came out a few years before the complete publication of the Ebla archive (1976). Like Röllig, Pettinato locates it on the Tigris, and Diakonoff east of the Tigris, although only Pettinato knew Kakmium from Ebla (Diakonoff 1956; Pettinato 1981, 216). Likewise, Westenholz states, “the earlier Kakmium is perhaps to be located in the Khabur region or even further to the west,” while Kakmum is “the area south of Lake Urmia” (1997, 248–50). Overall, little evidence supports the conflation of Kakmium and Kakmum as one state, despite their nearly identical names.

Eliminating the references to Northern Syria Kakmium yields a limited corpus of texts concerning Kakmum but spanning centuries. The earliest reference comes during a rebellion of a king of Simurrum, Puttimadal, against king Naram-Sin of Akkad, in which an unknown king of Kakmum joins in the uprising (Grayson and Sollberger 1976; Westenholz, Joan Goodnick 1997, 242–45, 248–53). While this text was likely composed later, it demonstrates that Kakmum may have begun as early as the Old Akkadian period. During the Ur III period Kakmum appears in their corpus only once. Despite the wealth of texts from the period, only one record of “two sheep for Dugra, men of Kakmu,” mention the polity, and the context provides little assistance in any historical reconstruction (Röllig 1976; Walker 1985, 193). Kakmum’s general absence in the Ur III texts may be because of its distance or geographic isolation from the core of that state. Despite the Ur III kings’ many campaigns into the mountains of Iran, those treks mainly occurred nearby the Old Khorasan Road, the primary access route across the Zagros Mountains into Iran, beginning near the Sirwan/Diyala River, near the findspot of the Annubanini Stele, far south of Soran (Steinkeller 2007; Alvarez-Mon 2013). The distances and obstacles between southern Mesopotamia and the northern Zagros Mountains may have insulated Kakmum from the Ur III kings’ advances. Near the end of the Ur III dynasty, Iddi(n)-Sin’s military campaigns began to reach Kakmum’s domains. The Simurrumian king’s Haladiny and Jerusalem Inscriptions detail conquests against Kakmum while expanding Simurrum’s borders to the north (Shaffer, Wasserman, and Seidl 2003, 1–11; Ahmed 2012, 255). Using the findspots and clues from those texts, Kakmum must be located north, northwest, or northeast of the Rania Plain.

After a small gap in time, Kakmum vigorously reappears in the textual record with a litany of political connections in the Tell Shemshara archive. The archives reference the only named king of Kakmum, Muškawe. The letters record an attack by Muškawe and his men against the city of Kigisbši, carrying away 100 sheep, 10 cows, and an unknown number of men, during the period contemporary to Šamši-Adad’s Old Assyrian reign (Eidem and Laessøe 2001, 24). Another letter dealing with the loyalties of Yašub-Addu of Aḫazum, the kingdom downstream of Dokan, demonstrates Kakmum’s role in the political system of the time. The letter is from Šamši-Adad to Kuwari of Šusara. In it, he expresses his disappointment and rage towards Yašub-Addu after that leader changed his allegiance from Šimurrum, to the Tirukkeans, to the ruler Ya’ilanum, to Šamši-Adad himself, before finally pledging fealty to the king of Kakmum (Eidem and Laessøe 2001, 23). Aḫazum is generally considered the land between the Rania Plain and Erbil, with its capital of Šikšabbum possibly located at the mound of Satu Qala (Laessøe 1985, 182; Eidem and Laessøe 2001, 22). Shifting alliances and allies are evidenced again in a letter by Pišendēn, a Turukkian king of the kingdom of Itabalḫum. He attempts to persuade the kingdoms of Elam, Namri, and Nikum to join in his struggle, promising “gold and costly things if they will make attacks on the land of Kakmum” (Eidem and Laessøe 2001, 143–44).

A further letter references Kakmum in the context of Šurutḫum, likely located at or near the Dukan Gorge. The letter states, “the face of Kakmu of Šurutḫum has turned to my lord. Rejoice!”(Eidem and Laessøe 2001, 110–11). The identity and location of Šurutḫum elucidate its relationship with Kakmum and that polity’s location. In an inscription of the Elamite ruler Šilḫak-Inšušinak, it occurs along with Arrapha, Nuza, Hašimar, and Zaban, all located in the area of the Lower Zab and Diyala Rivers (Astour 1987). More specifically, it occurs alongside the geographical name Šašrum in Ur III documents, indicating a location near the Rania Plain (Walker 1985, 107). A gorge in the text likely refers to the modern Dukan Gorge, bordering the Rania Plain (Astour 1987). The Kakmum in this letter does not refer to the polity, rather a person with an identical name. Šurutḫum thus may not be in the realm of Kakmum itself but may be close to it. Further letters from Tell Shemshara detail preparations for attacking Kakmum (Eidem and Laessøe 2001, 142–43).

Letters and inscriptions from areas distant to Šusara mention Kakmum, painting an image of a powerful and aggressive entity. Kakmum’s soldiers demonstrate clear military acumen in a letter reporting two men captured above (elûm) Ekallatum and detained in the palace of Kakmum (Frankena 1966, 28–29). The Akkadian word elûm contains multiple meanings, often translated as “above,” but carries the general impression of higher. It may likely refer to upstream or into the mountains from Ekallatum. Another instance, from soon after Šamši-Adad’s death, shows a contingent of Kakmi troops infiltrating what is commonly considered part of the Assyrian heartland. That letter describes a raiding force of 500 men from Kakmum, led by a ruler named Gurgurrum, defeating a force of 2000 men near Qabra (Lackenbacher 1988; Eidem and Laessøe 2001). Qabra’s exact location remains unknown, but it likely lies somewhere in the Assyrian heartland, not far from Ekallatum itself (Charpin 2004; MacGinnis 2013). Recent excavations at Kurd Qaburstan, west of Erbil, suggest identifying that site as Qabra (Schwartz et al. 2017). Kakmi troops again demonstrate excellence in battle by their role as mercenaries for the kings of Kurda and Karana in an invasion of Šubat-Enlil (Vincente 1992). Defeating these people in their mountain stronghold was a great accomplishment, which Hammurabi boasted about in the title of his 37th year, describing his victory over the Gutians, Turukku, Subartu, and Kakmum (Charpin 2004).

A handful of other texts reference Kakmum, revealing details about the nature of the people and the kingdom’s relationships. A text from Tell Rimah records a delivery of wine by people from Kakmum (Dalley 1976). From Mari, a letter mentions a messenger originating from Kakmum (Kupper 1954). From the waning days of the Old Babylonian dynasty, under Samsu-Iluna, a text describes the deportation of people from Arrapha and Kakmum to Babylonia (Ungnad 1920, 134). After the deportations recorded during Samsu-Iluna’s reign, references to Kakmum disappear in the historical record.

With this corpus of texts concerning Kakmum, the most likely location for this polity is in the northwestern Zagros, specifically in the modern Soran district. Previous scholarship disagreed on Kakmum’s location, but the entity was not the primary focus of the relevant studies. Astour proposed a location “between Ekallatum and Erbil,” possibly biased by the references to Kakmium in the Khabur (Astour 1987). The fact that Kakmum remained an enemy of Šamši-Adad after his capture of Erbil eliminates this location, as it would necessitate the improbable situation that Kakmum somehow remained independent and hostile while wholly surrounded by Šamši-Adad’s growing nascent empire (Eidem and Laessøe 2001, 23). Frayne placed Kakmum at Koy Sanjaq using the names’ morphological similarities, though this spot makes little sense given its proximity to Erbil, Ekallatum, and lack of isolation (Frayne 1999, 171). In the publication of the Tell Shemshara letters, Eidem and Laessøe (2001, 24) suggest a position between Sulaimaniya and Chemchamal, to the south of Tell Shemshara. However, Eidem previously envisioned Kakmum north of the Rania Plain and subsequently ruled out its location in the Pishdar Plain (Eidem 1985; Ahmed 2012). The lack of references to Kakmum in the Ur III campaigns and Iddi(n)-Sîn’s campaigns to the north seemingly rule out the placement between Sulaimaniya and Chemchamal. Westenholz believes Kakmum should be in “the area south of Lake Urmia or the northwest Zagros mountains,” agreeing with Röllig’s assessment (Röllig 1976, 19; 1997, 186). Shaffer and Wasserman read Kakmum as “Nimum,” in the Jerusalem Inscription, but they locate that toponym in “the area of present-day Ruwanduz [Rowanduz]” (2003, 28). Most recently, Ahmed (2012, 270–71) agreed with Shaffer and Wasserman’s location around Rowanduz. His only hesitation was the “lack of a plain territory suitable for abundant agricultural production, which was the basic economic activity together with animal husbandry of these old kingdoms” (Ahmed 2012, 271).

Two possible locations of Kakmum have sufficient evidence: north of the Rania Plain and the northwestern Zagros Mountains adjacent to Lake Urmia. Ahmed’s objection to Rowanduz is quickly rebutted by the large Diana Plain directly abutting Rowanduz and included in its logical political catchment. Documented routes predating the modern road construction reinforce the connection between Rowanduz and the Rania Plain to the south, providing additional evidence. Following the Handbook of Mesopotamia, a British colonial manuscript that records the various routes around Iraq, a popular travel itinerary left Rania, passed Betwate village (a possible location of Kulun(n)um), headed north, crossed the Korek Dagh, and descended to Rowanduz (Division 1917, 269–72). An alternate route passed Gulan village, followed another of the parallel north-south valleys to the Handrin valley, directly next to Rowanduz (Division 1917, 273–78). Further, two more passes onto the Urmia basin, the Gawra Schinke and Kelishin Passes, are located in this area, explaining the conflict between Turukku and Kakmum (Kenneth 1919).

There is little direct archaeological evidence for Kakmum in the Soran district because of limited knowledge regarding the kingdom and nascent excavations of Early Bronze Age material. However, a few sherds of Khabur Ware pottery at Gird-i Dasht, a large mound on the plain in Soran excavated by RAP (Chapter 1), indicate a connection between Mesopotamia and the plain during the Bronze Age. While Gird-i Dasht is one of the only possible candidates for a large Bronze Age city on the Diana Plain, the written description of Kakmum does not present a dense urban environment. Much like the Turukku are often written as a single ethnic entity despite clearly containing many constituent kingdoms and cities, Kakmum may refer to a quasi-ethnic group of confederated groups rather than a single point on a map. Kakmum was likely located between Utum to the south, Turukku to the east and Mesopotamian city-states to the west. The extent of Kakmum’s influence may have spanned from Spilik Pass in the west, to Sidekan and Kelishin Pass in the east, divided from the Turukku by the peaks of the Zagros Mountain;’s chaine magistrale. The absence of large Bronze Age sites or tells in the Soran district does not refute Kakmum’s location but corresponds well to the textual depiction of the kingdom’s few references to cities, spread out in small settlements around the area.

The question of Kakmum’s location is not purely an exercise in Bronze Age historical geography but may provide information about the founding of Urartu. After the use of the toponym ends in the Middle Bronze Age, it appears once again during the reign of Sargon II in the context of campaigns to the Iranian plateau. In Sargon II’s Letter to Aššur, one reference describes Urartu as the land Kakmê. The Assyrian king’s scribes used their Mannean allies’ name for the polity, as the only other descriptions of Urartu as Kakmê occur in the context of Mannea (Fuchs 1994, 440-41). However, this name for Urartu appears only during Sargon II’s reign. The Mannean terminology may reflect the ancestral roots of Urartu to the kingdom of Kakmum, an archaic term for the rulers of the Iron Age empire. However, use of this name occurs only under Sargon II and not in any of the recorded Mannean texts, casting doubt on this connection. The possible continuity of the name Kakmum through the centuries and the parallel political structure of the Turukku are data points in the understanding of Urartu and Muṣaṣir’s origins, discussed further in Chapter 7.

Late Bronze Age & Early Iron Age

Following Hammurabi’s reign, references to the area of Soran and Sidekan disappear from the historical record until Assyrian kings campaigned into this area, which they call Muṣaṣir. While the northern Zagros does not appear in available textual records, the region's history did not cease. To the south, on the plains of Mesopotamia, Babylon was ruled by the Kassite dynasty. Although the exact origins of the Kassite ruling elite are unknown, multiple scholars postulate that the rulers originated from the other side of the Zagros Mountains and, after a gradual migration, subsequently conquered Babylon and its people (Zadok 2013, 2–3; Liverani 2014, 364). The Kassite kings ruled over southern Mesopotamia for a notably long period, from sometime in the early 14th century BCE to about 1150 BCE (Clayden 1989, 47–52). Unlike the previous kings of Ur III and Old Babylonia, the ruling Kassites largely avoided distant expansionary campaigns. They primarily controlled central Mesopotamia, from the Middle Euphrates to the far south, the so-called Sealand (Liverani 2014, 364). The absence of long-distance campaigns, in large part, accounts for the lack of written records detailing actions in the northern Zagros. While Kassite dominion may have extended further from the Mesopotamian plains, up into sections of the central Zagros Mountains, there is no evidence of influence at Sar-i Pol Zohab, located near the Great Khorasan Road (Brinkman 1972, 277; Reade 1978). Reaching this area was possible as it avoided the core of the Assyrian state to the north. In the latter half of the Kassite period, the kings fought against and conducted treaties with a newly resurgent Assyrian state growing from its religious center at Aššur (Liverani 2014, 366). Around 1230 BCE, the Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta I soundly defeated the Kassites, sacking Babylon, taking king Kashtiliashu IV hostage, and conquering the southern state (Brinkman 1972, 276–77). Assyrian hegemony over Babylon lasted for seven years through a proxy king before a revolt in Assyria provided the weakness required for the Kassite king Adad-shum-usur to regain the throne (Liverani 2014, 366). In the mid-12th century, invading Elamite armies from southern Iran ended Kassite rule over Babylonia by sacking the capital (Brinkman 1972, 277). In the succeeding power vacuum, the kings of Assyria grew their state’s power into the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Unlike the Kassites, the Neo-Assyrian kings were quick to conduct campaigns outside of their core and had a particular affinity for operations in the Zagros Mountains. The Sidekan area would eventually be bounded on both sides by the powerful Neo-Assyrian and Urartian empires.

Assyria

The growth of the Neo-Assyrian state, from its founding days as the Middle Assyrian kingdom in the second millennium to its maximum extent ruling an empire from Egypt to Persia, is a near millennia-long tale of the emergence of the state, its contraction, and eventual rise to be the most powerful empire in the Near East. Postgate divides Assyrian territorial history into four phases: 1, creation and expansion (1400-1200 BCE); 2, recession, often referred to as a ‘dark age’ (1200-900 BCE); 3, re-establishment of borders (900-745 BCE); 4, final expansion deep into Egypt and Iran, often associated with the ‘Sargonic Kings’ (745-605) (Postgate 1992, 247–51). During the periods of expansion and foreign military campaigns, the accounts of the Neo-Assyrian rulers’ wars and battles against enemies help reconstruct the historical geography of the northern Zagros and the area’s relationship with the surrounding powers. Specifically, the Assyrian texts provide the most substantial historical documentation of Muṣaṣir. Throughout all phases, the Assyrian kings spent considerable blood and treasure to subdue the people in the mountains, including their northern neighbors, Urartu. The history of the Assyrians, as the consistent power to Sidekan’s west for centuries, provides insights into the interactions and identity of this intermontane region.

Assyria emerged early in the second millennium as the Old Assyrian kingdom under Šamši-Adad I, mentioned in the various battles of the Bronze Age. While the Old Assyrian kingdom’s power was short-lived, falling under the control of the Old Babylonian state not long after Šamši-Adad’s death, it would eventually form into the most powerful empire in the region. Centuries later, during Kassite rule in southern Mesopotamia, the Assyrian state began to form. From the 17th-14th centuries, the core Assyrian territory around Aššur and Nineveh fell under the direct and indirect control of the Mitanni state. Following the rule of Ishme-Dagan (1781-1741), the most notable documentation of the Assyrian rulers is the later “Assyrian King List,” until the steady rise of texts in the thirteenth century (Larsen 1976, 27–47; Kuhrt 1994, 348–49; Reade 2011, 1–8). Ruled by Indo-European kings out of a stronghold in the Khabur Triangle in modern Syria, the Mitanni state exerted considerable pressure and control on its neighbor (Liverani 2014, 290–93; 347–48). Under the reign of Aššur-uballit I (1365-1330), Assyria gained independence from their Mitanni overlords. Conflict between the Anatolian Hittite Empire and Mitanni during Aššur-uballit I’s reign, including the Hittite capture of much of the western Mitanni holdings, led to the murder of the Mitannian king Tushratta and a subsequent proxy battle over Mitanni royal succession (Wilhelm 1995, 1251–52). Aššur-uballit I, now a king on equal standing with Hatti, Kassite, and Babylonia, conquered areas of northern Mesopotamia around Nineveh and Erbil, while Tushratta’s son Shattiwza ruled a weakened state under the implicit authority of Hatti (Szuchman 2007, 4).

Fifty years later, Adad-nirari I (1307-1275) placed Shattiwaza’s son, Šattuara, on the Mitanni throne as a vassal. After a revolt by the Mitanni puppet, Adad-nirari I led a campaign against Mitanni, capturing multiple cities in the Khabur Triangle, like Taidu and Waššukani, and reducing the Mitanni kingdom to a regional power in the Upper Euphrates (Wilhelm 1995, 1253–54; Liverani 2014, 349–51). Upon his conquest, Adad-nirari created a new Assyrian provincial capital at Taidu, indicating complete annexation and solidifying control over the land (Harrak 1987). Adad-nirari I’s annexation of the Mitanni lands in the Khabur Triangle integrated this productive agricultural base into Assyria, permanently extending the core of Assyrian power. The original Assyrian territories in the Upper Tigris plus the addition of the Khabur Triangle created the core “Land of Aššur” (māt Aššur), or the “Yoke of Aššur” that would form the political and economic core of Assyria (Postgate 1992, 249).

At Middle-Assyria’s greatest extent, in the early 13th century, the powerful kings Shalmaneser I and Tukulti-Ninurta I conducted campaigns in neighboring lands and, in the case of Tukulti-Ninurta I, directly intervened in the politics of the neighboring powers by sacking Babylon (Yamada 2003). Although direct Assyrian control over Babylonia lasted for only a few years, the act of intervention in their southern neighbors was a sign of Assyria’s rise on the world stage. Assyria, during this time, stretched from the Zagros foothills to the upper Euphrates and the southern Taurus Mountains in Anatolia. Tiglath-pileser I marched across the Euphrates, extracting tribute, and reached the cosmologically esteemed Mediterranean Sea, an overt display of great power (Liverani 2014, 465). Another of his campaign texts describes a campaign against Muṣri, believed to be the forebearer of the Iron Age kingdom of Muṣaṣir. This text and previous references to the kingdom by 14th-century Assyrian kings denote the earliest record of interactions between Mesopotamian populations and Muṣaṣir. During this brief epoch of increased power, the Assyrian kings continuously attacked the people in the Zagros Mountains to the east, establishing a precedent for succeeding kings (Kuhrt 1994, 355–58).

Through the 12th century, Assyria maintained its premier status in the Near East. After the reign of Tiglath-pileser I, at the end of the 12th century, the Assyrian state would enter a period of contraction lasting for about three hundred years as it weathered the assaults from migrating ethnic groups in the surrounding regions. The state withdrew to its core of the “Land of Aššur.” Like the previous “dark age” between Old and Middle Assyria, the continuation of kings is known through the “Assyrian King List,” although surviving textual accounts provide a little documentation about the actions of individual kings. None of the neighboring powers, the southern Babylonians or the northern Hittites, maintained their strength during this time, as climatic change and vast numbers of migrating Arameans destabilized the whole region (Russell 1985, 58; Liverani 2014, 467). Advancing Arameans reached Nineveh and forced the Middle Assyrian kings to take refuge in the mountains of Kirruri, northeast of Assyria’s core (Tadmor 1958, 133–34). Analysis of the climate during this time indicates that periods of drought and climatic change precipitated this massive disruption in the political landscape of the region (Neumann and Parpola 1987). Despite the apparent mass migration of Arameans, archaeological evidence suggests a slower, long-term change, with conflict arising concurrently with changes in the climate (Szuchman 2007, 111–18; 53–160). Although the extent of Aramean migration in the Zagros Mountains is unknown, it provides a context to understand archaeological finds in the area dating to this period of Assyrian contraction in the west. Despite the small and weakened state, the Assyrian kings of this period did not cease their military operations. Kings like Aššur-bel-kala (1074-1057), ruling from the greatly weakened state centered around Aššur, maintained the strength to campaign in the mountains to the north, though focusing their efforts on holding back Aramean advances (Kuhrt 1994, 361–62).

Following the centuries of a small and weakened Assyria state, the kings Aššur-dan II and Adad-nirari II (934-912 and 911-891) began strengthening and reconstituting Assyria, marking the beginning of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Campaigns during their reigns occurred within the traditional boundaries of Assyrian control and focused on bringing the new, small Arameans cities and kingdoms under the direct control of the Assyria crown (Russell 1985; Liverani 2014, 475). Repeated campaigns, first by Aššur-dan II and his son Adad-nirari II, in areas held by their forebearers, solidified their holdings. Assyrian kings recast the conquered kings of vanquished territories previously under Middle Assyrian control as governors of this growing kingdom (Kuhrt 1994, 479). Under these kings and the following ruler, Tukulti-Ninurta II, Assyria expanded to reach its maximum size under the Middle Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta I. Tukulti-Ninurta II embarked on two marches, one to the south and one to the east, defining the limits of Neo-Assyrian influence at the time. To the west, he reached Muški, a kingdom that replaced Hatti’s core, and to the south, he marched along the Euphrates to Sippar, in the north of Babylonia (Liverani 2014, 476).

When the following king, Aššurnasirpal II (883-859), took the throne, Assyria began a period of mass expansion and campaigning around the Near East. Over fourteen campaigns, he expanded the state to include all areas lost over past generations and new territories to the north and southeast. Aggression by kingdoms in the northern Taurus Mountains, Nairi and Habhu, forced Aššurnasirpal II and his armies to conduct frequent campaigns and skirmishes. In the Upper Tigris, Assyria’s growing power and consolidation led to the pacification of the kingdom of Bit Zamani, near modern Diyarbakir, and the creation of a permanent Assyrian outpost, Tušan (Kuhrt 1994, 483). Despite the outpost, Nairi and Habhu maintained independence in the nearby mountains. Aššurnasirpal II also became the first king since Tukulti-Ninurta I, almost four centuries earlier, to march to the Mediterranean Sea, defeating the small kingdom of Bit Adini on his partly ceremonial journey (Liverani 2014, 479). To the southeast, he began expanding Assyria’s borders into the mountains, leading a series of campaigns against the kingdom of Zamua in the Shahrizor Plain and conquering the area (Levine 1973, 16–22). By establishing two colonies in the kingdom after this conquest, Aššurnasirpal II established a foothold in the Zagros Mountains that later kings would use as a base to launch mountain campaigns (Postgate 2000). Notably, in Aššurnasirpal II’s many campaigns, his forces never crossed further than the “first row” of hills surrounding Assyria (i.e., the first mountain range in the series of roughly parallel ranges extending into the higher mountains) (Liverani 2004, 217).

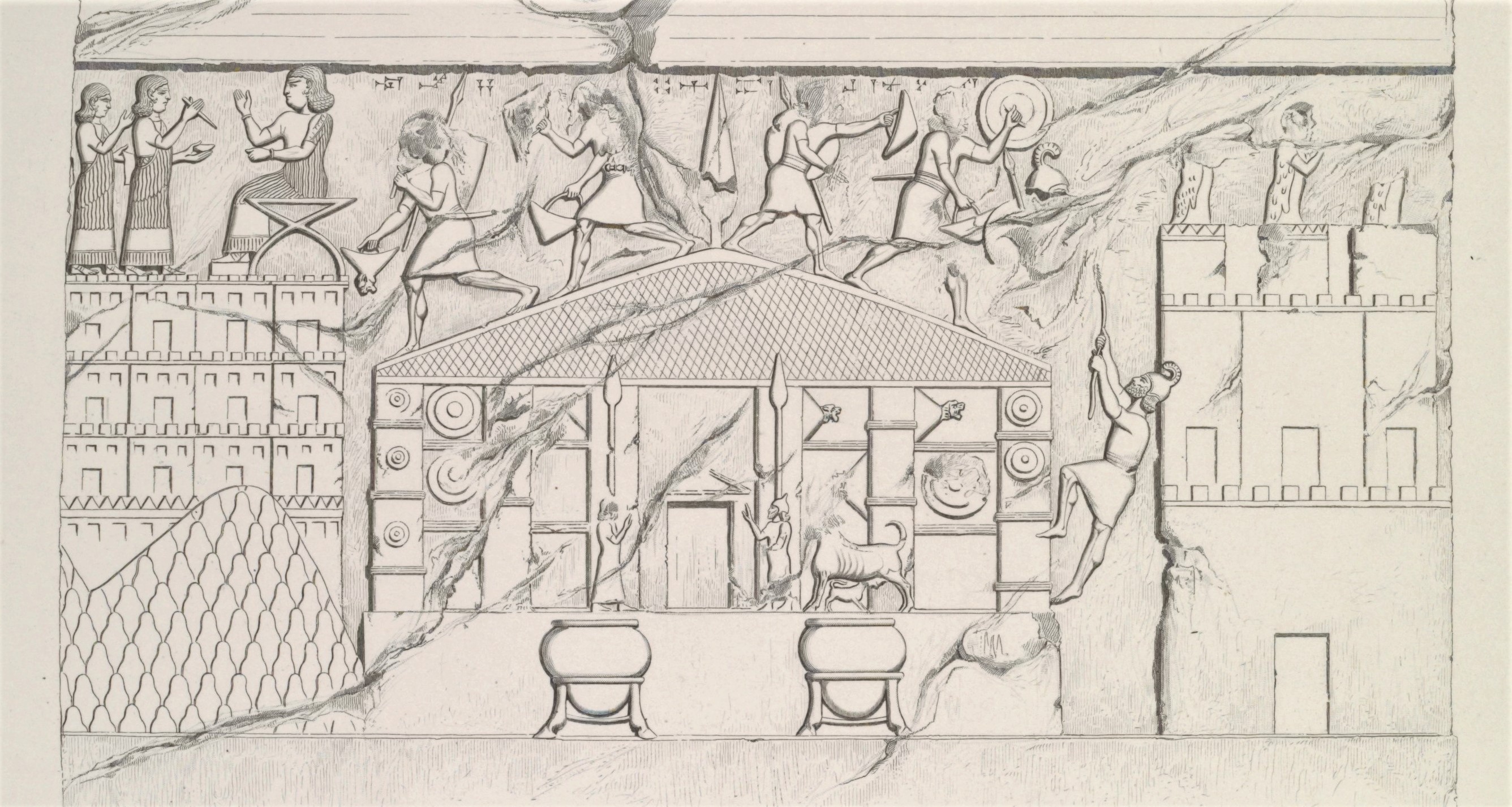

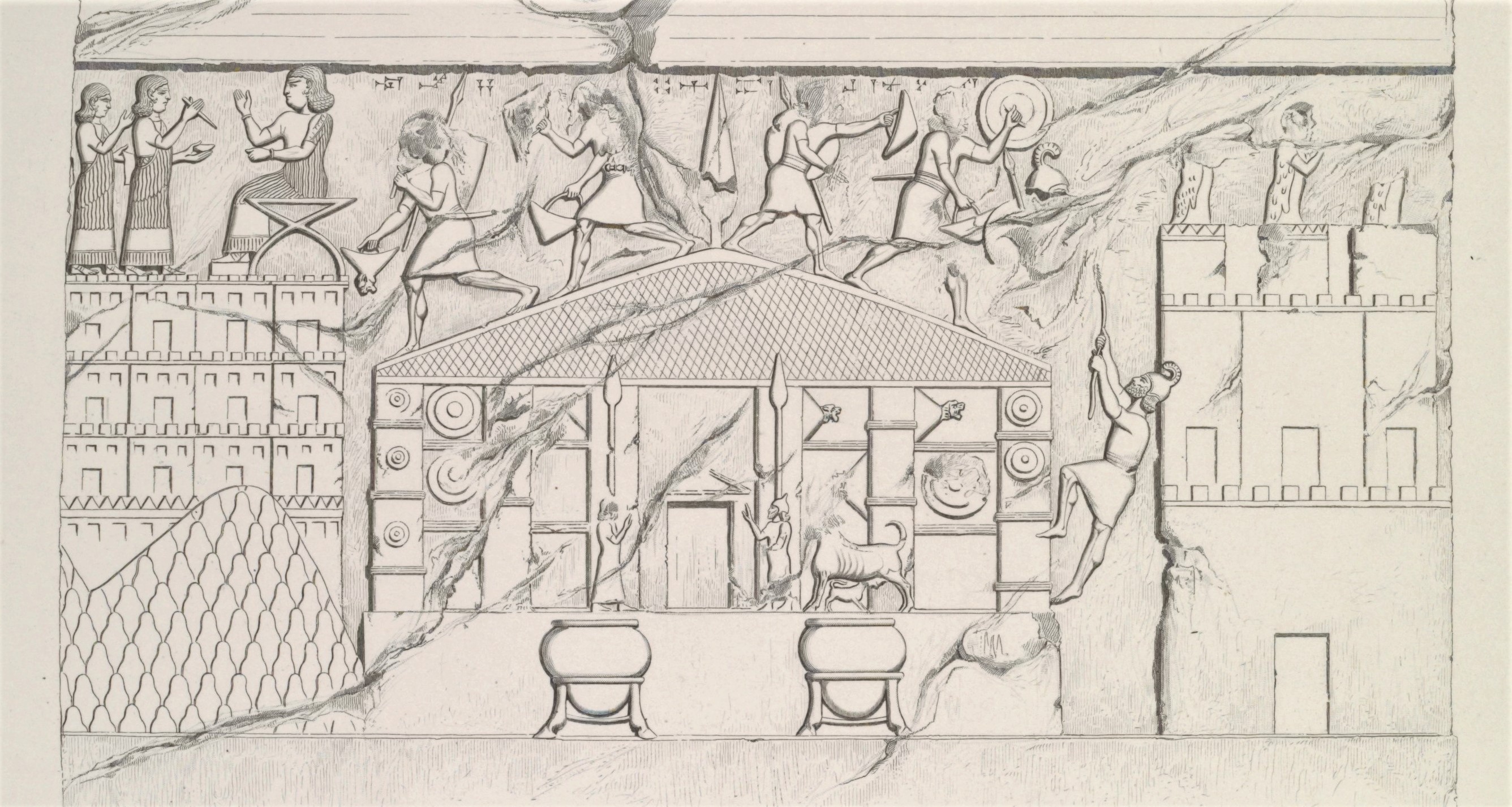

In addition to demonstrating the military power of Assyria and expanding the nascent empire’s borders, Aššurnasirpal II founded a new city, and with it created a new imperial ideology and style. In 879 BCE, Aššurnasirpal II began his reign ruling from Aššur, before moving the capital to Kalhu, the modern site of Nimrud (Radner 2015, 27). The city's construction was resource-intensive and set up in a planned manner, not unlike the later Roman cities that signified that empire’s imperial control (Mallowan 1966; Oates and Oates 2001). The city’s many inhabitants served to not only support the imperial war effort but produce a distinctly Neo-Assyrian style of art and architecture. Hundreds of stone reliefs detailing the king’s accomplishments and military victories, created in a style similar to the victory stelae of the Bronze Age, covered the walls of his newly constructed palace. Extensive texts providing itineraries of the campaigns were often included on the reliefs, creating in-depth reconstructions of the travel and battles (Oates 1963, 4). One of the most notable of Aššurnasirpal II’s, the Banquet Stele, describes his accomplishments through texts and imagery (Mallowan 1966, 57–73; Oates and Oates 2001). Excavations by Layard in the 19th century recovered many of the wall reliefs, providing a tremendous bounty of knowledge about not only Aššurnasirpal II’s campaigns but also how the Assyrians viewed their surrounding neighbors (Layard 1849). This style of documenting military victories, popularized at Nimrud, continued throughout the Neo-Assyrian kings’ campaigns. This and other Neo-Assyrian reliefs provide an invaluable dataset to reconstruct the historical geography of the surrounding regions.

Aššurnasirpal II’s successor, Shalmaneser III (858-824), continued his father’s policy of aggressive expansion, renewed with new zeal to bring new regions under Assyrian hegemony (Liverani 2014, 481). Shalmaneser III’s reign oversaw a reorganization of the Neo-Assyrian territories to maintain stability and better control. For the first time, the Assyrian armies fought far from the Assyrian homeland and conquered arduous territory. Specifically, using Liverani’s representation of the hills and mountains of the Zagros piedmont as “rows,” Shalmaneser III and his generals reached lands past the first row, including to the east of the chaine magistrale (Liverani 2004, 217). From the strongholds on the Upper Tigris that Aššurnasirpal II strengthened, Shalmaneser III’s armies campaigned into the northern mountains and brought the kingdoms of Gilzanu, Hubuškia, Melid, Alzi, and Dayaeni directly into the Assyrian sphere as vassals (Liverani 2014, 481). In the west, Shalmaneser III fought against an alliance of city-states in Syria at Qarqar, and in the east, his armies used Zamua to launch campaigns into the highlands of Iran (Russell 1984; Roaf 1990; Postgate 2000; Liverani 2004, 215; 2014, 482). To the south, the king of Babylon, Marduk-zakir-šumi, called upon the Assyrian king, justifying an earlier treaty, to help remove his brother, a usurper, from the throne of Babylon (Kuhrt 1994, 488–89). Despite the invitation to enter Babylon, the military act demonstrated a degree of power, signifying the king’s status in the Near East.

While Shalmaneser III and the Neo-Assyrian Empire reached new heights of power, in their north, a powerful new empire arose from the previously confederated states of Nairi: Urartu. Up to this time, Nairi appeared mainly as a geographic designation, but during Shalmaneser III’s reign the entity began to be referenced as a political organization (Luckenbill 1989, 232). Created out of the original lands of Nairi that threatened previous Assyrian kings, this state provided Shalmaneser III an additional adversary. Against this new power, directly adjacent to the Assyrian heartland, the Neo-Assyrian king conducted three campaigns; they penetrated into the heart of Urartu, around its heartland of modern Lake Van (Russell 1984, 171; Kroll et al. 2012, 10). These campaigns provide the first references to Urartu and are instrumental in understanding the origins of that kingdom (Chapter 7).

In addition, Shalmaneser III also embarked on campaigns into northwestern Iran, to the south of Lake Urmia, in the Mannean lands, departing from Zamua or nearby (Postgate 2000; Kroll 2012b). This region in the Iranian highlands would become part of an expansive Urartian empire under later kings. These two empires, Assyria and Urartu, quarreled as fierce adversaries, spending the next two centuries fighting nearly constantly, with Urartu successfully resisting full Assyrian domination.

At the end of Shalmaneser III’s long reign, a succession crisis overtook Assyria. Over four years Shalamenser III’s son, Shamshi-Adad V (823-811) fought against internal threats and usurpers, creating instability in Assyria (Kuhrt 1994, 490). After a short reign, his son, Adad-nirari III (810-783), ascended to the throne but left little of note in either textual records or expansionary actions (Liverani 2014, 482). Although both kings continued active campaigns during their reigns, the rapid expansion of the Neo-Assyrian state paused during these decades. From the death of Shalmaneser III to the rise of Tiglath-pileser III in 744, the empire existed in a period of relative stasis. However, one of these kings, Shalmaneser IV, mentions Urartu in five of his yearly reports in the Eponym Chronicles (Astour 1979, 4).

Upon Tiglath-pileser III’s accession to the throne (744-727), the Neo-Assyrian empire entered a period of expansion, subduing areas beyond its previous control. During the preceding decades of weak Assyrian rule, external factors created pressure on all flanks of the empire and led to Tiglath-pileser III’s many military campaigns (Kuhrt 1994, 498). Although he campaigned across the Near East, the record of his expedition north to Urartu serves as a vital document in the reconstruction and identification of polities in the mountains. During the power void in Assyria during the first half of the 8th century, Urartu utilized the relative peace to dramatically expand its borders (Liverani 2014, 487). In year two of Tiglath-pileser III’s reign, he and his army set out for Anatolia to capture areas under Urartian hegemony. Specifically, at the town of Arpad, in northern Syria, the Assyrian armies ambushed and forced the retreat of Urartian forces across the Euphrates River (Astour 1979; Tadmor, Yamada, and Novotny 2011, 13). In year ten, Tiglath-pileser III’s armies attacked Urartu, this time penetrating to the state’s capital of Turušpsa at Lake Van (Tadmor, Yamada, and Novotny 2011, 53–55). While the Assyrian king recorded this as a victory, he did not successfully capture territory or meaningfully slow the growth of the Urartian state.

After a short, four-year reign by Tiglath-pileser III’s son, Shalmaneser V (726-722), the usurper Sargon II seized the throne (Kuhrt 1994, 497). While Sargon II may have been a brother of Shalmaneser V, the evidence is uncertain. After putting down rebellions that took advantage of the apparent weakness of the kingdom, he embarked on many expansionary campaigns, significantly increasing the size of the empire. For the first time, Assyria’s influence reached the Mediterranean island of Cyprus, the king set up a new province of Tabal in Central Anatolia, and Sargon II not only assumed kingship over Babylonia but took up residence there (Liverani 2014, 490). Sargon II’s eighth campaign against Urartu is well documented and provides the most detailed account of Muṣaṣir. The campaign's details are inscribed on a clay tablet, often described as Sargon’s “Letter to Aššur,” which provides extensive details over its 430 lines (Muscarella 2006). Sargon II’s scribes also detailed the campaign in his annals which describe the full achievements of each year of his reign (Fuchs 1994). Sargon II and his armies defeated the Urartian forces south of Lake Urmia and ravaged the landscape before sacking Muṣaṣir and bringing it under Assyrian control. While this campaign wreaked considerable destruction upon Urartu and Sargon II’s depiction of the campaign implies the utter defeat of the kingdom, the Urartian kings continued ruling at least a century more. Sargon II’s military sucessses ended with his death on the battlefield in Anatolia while fighting in the province of Tabal (Tadmor 1958).

The conflicts between Urartu and Assyria provide ample documentation of the actions of individual kings and rulers and the many small cities and kingdoms between the major powers. One of these entities was Muṣaṣir, a small kingdom containing strategic and spiritual importance for the kings of Urartu and Assyria and the primary focus of this dissertation. This kingdom’s location was almost certainly in the upper reaches of the Upper Zab, in the Sidekan region. An overview of Urartian history and geography provides a foundation for understanding the location and characteristics of Muṣaṣir. Identifying the exact location requires understanding Urartian history, geography, and political organization.

Urartu

The spread of Urartu and the history of its ruling elite is documented by texts from the Urartians and accounts from their militaristic neighbors, the Assyrians. Most Urartian texts are stone inscriptions engraved on the foundation blocks of new buildings, stand-alone stone inscriptions, or rock reliefs (Kroll et al. 2012, 7). In the Corpus die testi Urarte (CTU), the definitive collection of Urartian texts, Salvini divides the texts into five categories: rock and stone inscriptions, inscriptions on bronze objects, inscriptions on clay, other materials, and seal inscriptions (Salvini 2012, 111). Despite these many categories, the inscriptions on stone are, as a whole, the only type that provide details concerning historical events (Salvini 2012, 115). Movable objects, like clay tablets and bronze objects, serve as indications of a ruler’s preference over a particular site or the development of Urartian art, although their mobility can obscure the exact origin of the text. However, the far larger corpus of stone inscriptions provide details about military accomplishments and building activities of monarchs (Kroll et al. 2012, 7–8). In contrast to the vast archives of tablets in neighboring Mesopotamia, the corpus of Urartian tablets numbers only about two dozen tablets. While these tablets occasionally contain interesting information about the history of Urartu, their use for an extensive analysis of the empire is limited. These texts primarily provide information on the spread of Urartian hegemony across the mountains of the Near East and the order of dynastic rule.

Table 1: Urartian King Chronology. Estimated dates from known synchronisms.

Urartian royal inscriptions, combined with Assyrian synchronisms, aid in reconstructing the order and the length of Urartian kings’ reigns. Many royal stone-cut inscriptions are bilingual, written in Urartian and Assyrian, or exclusively in the Urartian language. As Assyrian and Urartian are distinct languages with different linguistic foundations, Semitic and Hurrian, each language uses different words for proper nouns. The most notable example is the name of the state itself. The Assyrians called this entity Urartu, while in the native language of the Urartians, the kingdom was named Biainili (Kroll et al. 2012, 8). Following convention, the Urartians and their geographic entities are referred to here using the Assyrian terms, when available. Some exceptions are Urartian spellings of geographic names with no known Assyrian parallel and Urartian kings’ names.

When referring to the monarch, the Urartian inscriptions only give the ruler’s name with a single patrionymic, referencing the king’s father but no other relatives (Fuchs 2012, 159; Kroll et al. 2012, 8; Zimansky 2012b, 101). Traditionally, similarly named rulers are traditionally assigned sequential numbers based on these familial connections, such as Sarduri I and Sarduri II. As the Urartians lacked a king list, like those in Mesopotamia, these succeeding digits in the names are modern conventions reflecting the commonly understood order of dynastic succession (Zimansky 2012b, 101). In addition, the primary source of synchronisms, the Assyrian texts, do not refer to the Urartian kings with patronymics, complicating the reconstruction of the order. While most of the Urartian kings’ positions in the chronology are secure, uncertainty over a few monarchs necessitates a different way to differentiate rulers of the same name. Given the existence of a patronym for all but the first king of Urartu, Roaf (2007, 187) uses a convention of indicating the specific royal name by a single letter representing the father. For example, Sarduri L and Sarduri A rather than Sarduri I and Sarduri II.

The earliest known mention of Urartu comes from the reign of Shalmaneser I in the 13th century, who records conquering the land of “Uruátri.” At this time, the Assyrians used Uruatri as a geographic designation, not as the name of a unified polity. Contained in Uruatri were eight discrete states, suggesting the federated nature of the area (Grayson 1987, A.0.77.1: 32-36). Though not confirmed, the linkage between this name and the later Urartu is highly likely. A connection between Nairi and Urartu provides substantial evidence to equate the two terms (Salvini 1967). Second-millennium accounts of campaigns against Uruatri and Nairi describe the area as a collection of cities and states, analogous to a confederation rather than a single entity. Shalmaneser I’s son, Tukulti-Ninurta I, campaigned north, defeating forty kings of Nairi and reaching the “Upper Sea of Nairi,” believed to reference Lake Van (Barnett 1982, 320). Nairi is referenced a century later by the Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser I, who boasts of his successful battle against twenty-three kings of Nairi (Grayson 1972, 12–13). More than a boast, the Yoncali Inscription in the northeast of Lake Van, erected by Tiglath-pileser, confirms the Assyrian invaders entered into the heart of Nairi and is the most persuasive evidence for identifying that lake as the “Upper Sea of Nairi” (Grayson 1972, 38).

After the period of relative decline in Assyria, the Neo-Assyrian king Shalmaneser III records the first conflict against a seemingly unified kingdom of Urartu. Shalmaneser III launched three campaigns against Urartu, in his accession year, 3rd year, and 15th year (859, 856, and 844 BCE), specifically against a man named “Ar(am)amu/e,” a.k.a. Arame, described as the king of Urartu, and in the process, destroys the royal capital of Arzaškun (Fuchs 2012, 135–38). The location of this city is unknown, and later references to Urartu omit any mention of this toponym (Burney 1957, 39). Salvini (1995) suggests a location in the south of Lake Urmia, while Kroll (2012b), Schachner (2007), and Burney (2002) believe the city was near the eventual Urartian core of Lake Van (discussed further in Chapter 7). The name Arame only appears in the Assyrian texts which, combined with the connections to the Assyrian designation for Aramean, led Salvini to argue that this name referred to an unnamed Aramaic ruler of Urartu (Salvini 1995, 26–27). In Salvini’s interpretation of Aramu as Aramean, a ruling class of Urartians, literate in a linguistically Hurrian Urartian dialect, overthrew Arameans rulers, of which Aramu was one. Fuchs, however, refutes this interpretation and believes the name refers to a specific ruler, possibly the Urartian ruler Erimena (Fuchs 2012, 159). While the connection of Arame and Erimenea is unlikely, discussed below, there is no reason to suspect Arame was Aramean, apart from linguistic similarities.

At the end of Shalmaneser III’s long reign, in 830 BCE, he fought a new ruler of Urartu, named “Serduri (Fuchs 2012, 135). This king is undoubtedly the same ruler that Urartian inscriptions named Sarduri (I), son of Lutipri, whose name adorned a series of six inscriptions around Lake Van. Notably, Sarduri’s inscriptions are the first at the fortress of Tušpa, the new capital of Urartu. The connection between Sarduri L and Arame, specifically the lack of stated familial connections in the Assyrian texts, is a crucial point of debate concerning the nature of the origins of the Urartian elites and the royal dynasty. With Sarduri L, an unbroken chain of Urartian kings begins, corroborating Assyria details.

In 820 BCE, the Assyrian king Šamši-Adad V attacked an Urartian named “Ushpina,” surely an Assyrian version of the name of the Urartian king Išpuini (Fuchs 2012, 139; Kroll et al. 2012, 10). Following this campaign, the two empires entered a period of relative peace and coexistence until 781 BCE (Fuchs 2012, 140). During this period, Išpuini and his son Minua reigned over Urartu (Grekyan 2006). The two Urartian rulers displayed a unique practice of inscriptions with both Išpuini and his son’s names. In the early years of Išpuini’s rule, the inscriptions bear only his name, while inscriptions in later years invoke him and his son. Minua’s name in inscriptions leads some to believe that Minua ruled as a crown prince in the later days of Išpuini’s reign (Çifçi 2017). Minua’s inclusion on the Kelishin Stele could commemorate a pilgrimage to Muṣaṣir to crown Minua as crown prince, although that interpretation is open to considerable debate (Chapter 7). Apart from the coexistence of royal names, the only other evidence of an Urartian crown comes a half-century later, in the account of Sargon II’s sack of the Ḫaldi temple where he states that the Urartian king. The evidence that Minua served as the crown prince is refuted in part by the absence of special titles for Minua in the inscriptions of his father (Kroll et al. 2012, n. 23).

After a decades-long period of relative coexistence between Assyria and Urartu, the Neo-Assyrian king Shalmaneser IV conducted campaigns against Urartu every year between 781 – 778 BCE (Millard 1994, 58). The Assyrians launched another campaign in 776 BCE, followed by an Assyrian field marshal’s victory over Urartian king Argišti in Western Iran (Fuchs 2012, 140). Argišti’s patronymic describes him as the son of Minua. Given that the last synchronism between Assyria and Urartu was Ushpina in 820 BCE, followed by Argišti in 776 BCE, Minua’s entire reign existed in those 44 years. In a sign of the imperfect nature of campaigns as historical records, Argišti’s annals describe a victory over the Assyrians, a campaign the Assyrians record as a triumph by their forces (Fuchs 2012, 150).

Argišti’s son, Sarduri A (II), provides one of the most detailed accounts of an Urartian king’s various military and construction activities in his Sarduri Annals, inscribed near the Urartian capital at Lake Van (Fuchs 2012, 150). This text and corresponding military campaign inscriptions around the region describe Sarduri A’s conflicts with Assyria, Melitea (the same entity as Hati/Ḫatti), Mannea, and Qumaha in the upper headwaters of the Euphrates (Fuchs 2012, 153–55). The annals boast of a victory against the Neo-Assyrian king “Aššurnirarini Adadinirariehi,” an Urartian rendering of the Assyrian ruler Aššur-nerari V, son of Adad-nerari III, in Sarduri’s 2nd year. Utilizing Assyrian sources and their royal chronology dates this event sometime between 755 and 753 BCE, given the reports of Urartian campaigns by the Assyrian kings (Fuchs 2012, 153–54). Aššur-nerari V’s successor, Tiglath-pileser III, records a victory over Ištar-duri/Sarduri in 743 BCE, indicating at least another decade of the Urartian king’s rule. Eight years later, in 735 BCE, Tiglath-pileser III again attacks Sarduri, besieging the Urartian king inside his capital of Tušpa at Lake Van (Fuchs 2012, 136).

After the reign of Sarduri A, the next Urartian king mentioned in an Assyrian text is Ursa/Rusa, an opponent of Sargon II in his eighth campaign (714 BCE). Unfortunately, given the lack of patronymics in the Assyrian text and the existence of multiple kings named Rusa in Urartu, the identity of this king is under debate. Chronologies from the last century of scholarship assumed that Rusa, son of Sarduri, refers to the king immediately following Sarduri II, the grandson of Argišti, and the Ursa mentioned in Sargon II’s campaign (Zimansky 1990; Salvini 2008, 23; Kroll et al. 2012). Lehman-Haupt proposed in 1921 that Rusa S was the enemy of Sargon II, contrasting Thureau-Dangin’s earlier proposal (Lehmann-Haupt 1921). Thureau-Dangin placed king Rusa, son of Erimena, as the adversary of Sargon II in the text (Thureau-Dangin 1912, xix n.3). Following Lehman-Haupt’s chronology, most publications maintained the successive order of Urartian kings with Rusa E in the waning days of the kingdom (Roaf 2007; Salvini 2008). Recently, Roaf, Seidel, and Kroll argued for Rusa E’s rule before that of Argishti, son of Rusa (Seidl 2004, 124; 2007, 140–41; 2012; Roaf 2007; 2012a; 2012b; Kroll 2012a). Roaf takes the stance that not only did Rusa E rule before Argišti R, but the most likely order of succession was Sarduri A, Rusa E, Rusa S, then Argišti R (Roaf 2007, 2012a, 2012b). To summarize, the argument rests on three points: the evolution of royal iconography, the identity of the founder of the fortress of Rusahinili/Toprakkale, and connections to the events in Muṣaṣir.

The first argument for Rusa E’s earlier dating relies on the stylistic features of lions and bulls on shields and other bronze objects from Rusa E and his Urartian noble peers (Seidl 2004, 124). Lions depicted on Rusa E’s inscribed and decorated objects have short bodies as well as tufts of hair on the mane, while the end of the tails resemble those of the earlier Sarduri A and Argišti M and are dissimilar to those of Rusa S and Rusa A (Seidl 2004, 124). Lions of Rusa E have a specific and unique feature of double cusps along the legs that are missing from those of Sarduri A and Argišti M (Seidl 2007, 140–41). These combinations of features triangulate the stylistic dating after the tenures of Sarduri A and Argišti M but before Argišti R. Seidl does not attempt to determine the order of Rusa E and Rusa S in this period (Seidl 2012, 181).

The fortress of Toprakkale, named Rusahinili by its eponymous Urartian founder, contains inscriptions on tablets and bronze objects by Argišti R and Rusa E (Seidl 2004, 42–43; Salvini 2007). While no monumental stone inscription originates from the site itself, at the nearby artificial reservoir of Kesis Göl several fragments from stone inscriptions boast of how a king named Rusa built the lake and the canals that bring water into its basin (Belck and Lehmann-Haupt 1892; Lehmann-Haupt 1926, 42–45). While Belck and Lehmann-Haupt believed Rusa S was the king in the inscription, a recent discovery of corresponding fragments and parallel texts has established that the Rusa in these texts was Rusa E, confirming that he was the founder of Rusahinili (Salvini 2002; Seidl 2012, 178). In addition, the inscription does not provide a qualifier to the name Rusahinili, which indicates there was not a pre-existing fortress founded by an earlier king Rusa. Thus, the fortress of Rusahinili Eidurukai (modern Ayanis) by Rusa Argišti must post-date the Rusahinili (E)’s founding (Çilingiroğlu and Salvini 2001).

While Sargon II’s eighth campaign describes his attack on Ursa, it does not specify which Urartian named Ursa (Rusa). Details from Rusa’s reign and Assyria's relationship with the ruler Ursa assist in determining which Rusa was Sargon II’s adversary. First, when Sargon II ascended the throne, Rusa had transgressed against Urartu “before my [Sargon II’s] time,” indicating Rusa had ruled for at least eight years prior. Second, in Sargon II’s march through Urartu after his defeat of Rusa’s armies, he says he “went to Arbu, Rusa’s ancestral city, and to the city Riar, the city of Ištar-duri [Sarduri].” The juxtaposition between the ancestral home of Rusa and the city of Sarduri implies distinct family trees, as the ancestral home of Rusa S would presumably be the city of Sarduri (Roaf 2012a, 200). Rusa E’s father, Erimena, was never an attested ruler of Urartu and would not necessarily descend from the Sarduri family tree.

Further evidence that supports Rusa E’s forceful takeover of Urartu is an inscription on a statue of Rusa from Muṣaṣir, reported in Sargon II’s Letter to Aššur. The engraving allegedly read, “With the help of my two horses and my groom, I personally obtain the kingship of the land Urartu.” The Assyrian text does not specify which Rusa, but Rusa E overthrowing the ruling dynasty is consistent with him obtaining kingship by force versus coronation by his father. Finally, in the Topzawa Stele, the king erecting the text is Rusa Sarduri (Boehmer 1978). Although there is some debate over the exact timing of the event described in the stele, the most likely date is 713 BCE (Roaf 2010, 79; this volume, 89). If the suicide of Rusa that Sargon II boasts was based in reality, the death of a king named Rusa occurred in 714/713 BCE (Roaf 2012b). Thus, the Urartian king ruling after the death of Sargon II’s adversary Rusa is Rusa S, creating a chronology of Sarduri A, Rusa E, Rusa S. Rusa E may have been a usurper to the throne or ascended through a different process not seen in the available texts.

Soon after Sargon II’s campaign into Iran, the Assyrian sources speak of a new Urartian king, Argišti. A vassal of Sargon II, Mutatallu of Kummuhi, allied with the Urartian king and revolted against the Assyrian monarch (Fuchs 1994, 112–13). This event occurred sometime between 710 and 708, as Sennacherib, as crown prince, reports on the vassal’s treachery to his father Sargon II in Babylon (Fuchs 2012, 137). The absence of an emissary of Mutalllu during Sargon II’s battle at Bit-Jakin in 709 BCE suggests that year for the date of separation (Fuchs 1994, 384). The Argišti in the Assyrian sources undoubtedly corresponds to Argišti, son of Rusa (Kroll et al. 2012, 18). After the short interval between king Rusa and Argišti of only five years, it is decades before Assyrian inscriptions mention another Urartian king. Direct conflict between Assyria and Urartu ceased after Sargon II’s eighth campaign until 673 BCE, likely precipitated by the seemingly ineffective Assyrian campaigns and the rise of a mutual adversary, the Cimmerians (Fuchs 2012, 142).

In a series of letters that Sennacherib sends to his father Sargon II during this time, the Assyrian crown prince describes attacks by a foreign group, the Cimmerians, against the Urartians. While the exact date of the letters is unknown, the attack almost certainly occurred after Sargon II’s eighth campaign and once Argišti ascended to the throne (Fuchs 2012, 155–56). In two letters, Urzana, king of Muṣaṣir, is mentioned as ruling in his kingdom and reporting to the spies and agents of Assyria about the Cimmerian army’s movement to attack the Urartian king. While Urzana’s letter aligns the Muṣaṣirian ruler’s reign with the Cimmerian invasion, curiously, SAA 5 145 describes the king of Urartu as Sarduri, ruling from Tušpa. This complication requires either a misattribution of the Urartian king’s name or implies that the Cimmerians invaded far earlier, somehow predating Rusa’s rule and Sargon II’s eighth campaign. The latter interpretation has no other evidence to support that sequence of events, so we must assume the king’s name was simply incorrect. Regardless, the king ruling over Urartu during the Cimmerian invasion is most likely Argišti R (Fuchs 2012, 155–57). Although early scholarship attributed the end of Urartu to this time, the son of Argišti R reappears in the Assyrian texts a few decades later.

In texts from his reign, the Neo-Assyrian king Esarhaddon (681-669 BCE) describes his conquest over the land of Subria and records sending Urartian prisoners to Ursa/Rusa, king of Urartu (673/672 BCE) (Fuchs 2012, 137). The Rusa in this text must refer to Rusa, son of Argišti, known from over a dozen Urartian royal inscriptions (Salvini 2008, 563–92). However, not long after this account, the Urartian Empire seems to become irrelevant. In an epigraph of Aššurbanipal detailing his victory over the Elamite king Teumann, the king of Urartu, Rusa, sent emissaries to the Assyrian royal court’s celebration (652 BCE) (Fuchs 2012, 137). In 646 BCE, the Assyrian report an Urartian king named Ištar-duri (Sarduri) sent tribute to the Neo-Assyrian king Aššurbanipal (Fuchs 2012, 138). In the Assyrian text, Sarduri is no longer an equal but a subservient kingdom forced to submit to the larger and more powerful Neo-Assyrian empire. Around this time, the existence of the Urartian state seems to cease, although no exact date provides a definitive endpoint. The growing Median and Babylonian empires and migratory forces from the east eliminated the independent Urartian state. In Neo-Babylonian texts, a geographic entity named Uraštu, thought to relate to Urartu, appears, although it has no political structure of note (Horowitz 1998, 20).

The construction of fortresses and accompanying royal inscriptions reveal the pattern and chronology of the Urartian empire’s imperial expansion, beginning around Lake Van and eventually spanning an area from the central Zagros Mountains to the Caucuses. The kings of Urartu established their power and grew the empire by constructing large, imposing fortresses across the landscape as they subdued local leaders and levied new governmental systems over the people (Zimansky 1985; Smith 1996). Urartu’s empire spread from its power base around Lake Van, first towards Lake Urmia, then to the northeast, to Armenia, before continuing further west and northwest in Anatolia. This order of growing control is documented reasonably clearly by the stone inscriptions of the kings. Two types of inscriptions serve as physical signifiers of Urartian power, building inscriptions and stone stelae. Building inscriptions, most often built as part of Urartian fortresses, correspond with semi-permanent administrative control and integration into the empire, while stone stelae are more often associated with campaigns in areas outside the direct control of the state (Kroll et al. 2012).

The first Urartian king, Arame, is known only from Assyrian accounts, and no texts in Urartu exist that would help locate the extent of Urartu during this time or the exact location of his apparent capital Arzaškun. The next recorded king of Urartu, Sarduri L, founded the capital from which all subsequent kings would rule. At Tušpa, the modern site of Van Kalesi near Lake Van, the capital of the emerging Urartian state, Sarduri placed building inscriptions, written in Assyrian, establishing himself as the first Urartian king to rule from the city (Salvini 2005). Sarduri L erected another eight inscriptions, written in Assyrian, on stock blocks around Lake Van (Salvini 2008). Given these physical markers, Sarduri L’s power seems to be concentrated around Lake Van, although he and his armies may have campaigned further afield.

Sarduri L’s son, Išpuini, commemorated many building activities on inscriptions around Lake Van. As discussed, in many of the inscriptions of Išpuini, his son Minua’s name also appears. These dual texts that share both names are almost certainly from the later part of Išpuini’s reign; thus, texts with only Išpuini's name may signify an earlier time in his tenure. The texts that bear only Išpuini’s name are limited geographically to the Lake Van basin and do not include any military campaigns (Kroll et al. 2012, 13). However, the inscriptions of their joint military campaigns show the quick spread of Urartian power during this time.